Gerard Manley Hopkins burned all of his poems before becoming a priest. He called his act the “slaughter of the innocents.” Jesuits begin their study with a two-year novitiate period, during which Hopkins did not write a single line of verse — in fact, he would only write fragments for the next seven years.

Hopkins struggled with the divergent pulls of poetry and prayer. That tension coaxed his best and most unique material. A sensitive ascetic with a wild soul and progressive syntax, he praised God by finding the divine in all things. The burning of his verse was not the end of his poetic life, but a cleansing and rebirth by fire: the start of a long, imperfect struggle.

We burn old love letters and photographs to be reborn. The action of burning is often a process. Find a match or a lighter. Put the papers in a container or can or shove them in a fireplace. There are so many moments along the way when we can have second thoughts, when we can decide to put memories in a drawer rather than reduce them to ash, but it is so tempting and comforting to watch the flames swallow our pain.

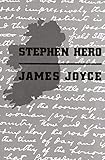

Hopkins is not the only writer to set fire to his creations. According to his biographers, Franz Kafka burned nearly 90 percent of his life’s work—and requested that more be burned upon his death (it wasn’t). Sylvia Beach, who later published Ulysses, claimed that James Joyce tried to burn his manuscript for Stephen Hero: “When the manuscript came back to its author, after the twentieth publisher had rejected it, he threw it in the fire, from which Mrs. Joyce, at the risk of burning her hands, rescued these pages.” The book would later become A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, in which Stephen Dedalus burns his poems because “they were romantic.”

Hopkins is not the only writer to set fire to his creations. According to his biographers, Franz Kafka burned nearly 90 percent of his life’s work—and requested that more be burned upon his death (it wasn’t). Sylvia Beach, who later published Ulysses, claimed that James Joyce tried to burn his manuscript for Stephen Hero: “When the manuscript came back to its author, after the twentieth publisher had rejected it, he threw it in the fire, from which Mrs. Joyce, at the risk of burning her hands, rescued these pages.” The book would later become A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, in which Stephen Dedalus burns his poems because “they were romantic.”

Writers’ manuscripts have notoriously been burned by other people. Thomas Carlyle wrote a history of the French Revolution, and gave it to John Stuart Mill for comment. Mill’s maid had charred the manuscript by mistake — she thought it was wastepaper, which is quite the burn. Sir Richard Francis Burton’s wife Isabel torched over a thousand pages of his translation-in-progress of The Scented Garden. V.S. Pritchett’s father made him burn a partial novel that he’d written as a child and “mocked my use of pretentious words.” Lord Byron’s memoirs were burned a month after his death, never to be published for fear of what they would do to his already controversial reputation. Ted Hughes burned a journal that contained “the last months” of Sylvia Plath’s life so that her children would never find the pages. There are numerous examples of governments and institutions putting books into bonfires, but they are still actions of external protest and censure. When writers burn their own manuscripts, they are destroying their own words. Cathartic, but also a bit sadistic. Burning is a slow, ritualistic death. Why not simply throw away a manuscript?

Writers’ manuscripts have notoriously been burned by other people. Thomas Carlyle wrote a history of the French Revolution, and gave it to John Stuart Mill for comment. Mill’s maid had charred the manuscript by mistake — she thought it was wastepaper, which is quite the burn. Sir Richard Francis Burton’s wife Isabel torched over a thousand pages of his translation-in-progress of The Scented Garden. V.S. Pritchett’s father made him burn a partial novel that he’d written as a child and “mocked my use of pretentious words.” Lord Byron’s memoirs were burned a month after his death, never to be published for fear of what they would do to his already controversial reputation. Ted Hughes burned a journal that contained “the last months” of Sylvia Plath’s life so that her children would never find the pages. There are numerous examples of governments and institutions putting books into bonfires, but they are still actions of external protest and censure. When writers burn their own manuscripts, they are destroying their own words. Cathartic, but also a bit sadistic. Burning is a slow, ritualistic death. Why not simply throw away a manuscript?

Writers are nothing if not melodramatic. Nikolai Gogol asked Leo Tolstoy to hold his manuscript for the second Dead Souls, but Tolstoy refused. Gogol had already burned a copy of it in 1845, and ultimately burned the rest in 1852. Eudora Welty said she would “burn everything up” to stymie potential biographers—everything as in personal correspondence, not manuscripts. Daniel Alarcón would burn his diaries as well: “that’s the space where I criticize people and am totally inarticulate.” Kenzaburō Ōe said he wanted to burn all of his unfinished manuscripts before he died, but there is no sign that he burned finished ones.

Writers are nothing if not melodramatic. Nikolai Gogol asked Leo Tolstoy to hold his manuscript for the second Dead Souls, but Tolstoy refused. Gogol had already burned a copy of it in 1845, and ultimately burned the rest in 1852. Eudora Welty said she would “burn everything up” to stymie potential biographers—everything as in personal correspondence, not manuscripts. Daniel Alarcón would burn his diaries as well: “that’s the space where I criticize people and am totally inarticulate.” Kenzaburō Ōe said he wanted to burn all of his unfinished manuscripts before he died, but there is no sign that he burned finished ones.

Umberto Eco said “later in life good poets burn their early poetry, and bad poets publish it.” Poet Karl Shapiro put all of his notebooks “in the furnace” when he was 23. Who among us doesn’t wish that we could incinerate some of our early publications? Ottessa Moshfegh was at her family’s summer home in Maine when she ran out of newspapers for a wood stove fire and burned some of her writing, “which put me in a dark philosophical place.”

I’ve only burned one manuscript — the first draft of my first attempt at a novel. I had kept the printed pages in a cardboard box in the garage, deluded that I might return to them years later and finally discover why agents weren’t interested. Instead the pages sat there and collected sawdust and grass clippings. When my wife and I bought a new house, I decided to get rid of the box. I took the first twenty or so pages to the fire pit in our backyard. That night we roasted hot dogs and their oils dripped on my first chapter.

That was years ago. Now, like so many writers, most of my manuscripts live exclusively on my computer screen. Burnt manuscripts seem outdated. They belong in the days of typewriters. Yet writers are no less wracked with self-doubt, anxiety, and frustration than they were in earlier generations. We might not tear our terrible pages out of the typewriter, but we are still often unhappy with what we create.

The emotions that have led writers to burn manuscripts will never disappear. All that has changed is our medium. When I hate a story that I’ve written, I move it to a folder labeled “Writing” on my desktop. Then I drag it to a subfolder labeled “Old Work,” and let it sit there. Grow digital moss. Become forgotten. Yet that action is like stuffing old sneakers into a closet rather than throwing them in the trash. Part of me hopes that the story will be recycled; that a character or even a sentence will migrate into some later work.

If you burn your only copy of a manuscript, you are making a statement: it’s over. There’s simply not as much drama moving a file to the trash bin of your computer as there is watching a conflagration smother your words. So here’s my advice to contemporary writers. Print a copy of that story you hate. Drag the file to the trash bin and make sure the file is permanently deleted. Then take that printed manuscript to a fireplace, or better yet, a bonfire. Set it aflame. Watch the paper blacken and wrinkle. Sometimes we need to burn our pasts, literary or not, to move forward. Trust that your words and secrets are safe, clouded in smoke, soon to become part of the sky.

Image Credit: Pexels/Movidagrafica.