For those among the world’s inhabitants who take for granted that one day, in some far flung corner of the cosmos, a preternaturally melancholic being — earthling or otherwise — will come by chance to hear a Leonard Cohen song and thereby be made if not suddenly blissful then at least able to enjoy his, her, or its melancholy a little more, a recent edition of Rolling Stone will hold interest. In an interview timed to coincide with the release of Mr. Cohen’s 13th studio album, an event in turn coinciding with his 80th birthday, the man says essentially that he cares not at all what becomes of his work after he dies, nor what his legacy will be. The music? The poems? The novels? The life? He could give a damn.

Ouch, a Cohen believer might predictably reply.

They who tend to be a mite sensitive to begin with. And remember also the bad old days, before the present éminence grise phase of the career. When to speak too lovingly about Leonard Cohen was a sure way to get one’s emotional stability called into question. So now might be excused for getting their backs up. Certain that a blasphemy has gone down, in an “et tu, Brute” kind of way.

At least that’s what I feel, but why? What is it about Leonard Cohen that not only commands my interest but can also set off no small burst of emotion? Something else, too: what exactly is my legitimate stake in someone else’s posterity? Even as a fan. Somewhere in my bones I hear my late grandmother putting it this way: if Leonard Cohen doesn’t care what becomes of his work and legacy after he dies — what’s that your business?

Theory # 1: Adolescent Attachments

Like many people, whether they know it or not, my adolescence extended well into my 20s. With the most challenging aspect coming all at once, after college, and brought on by what at the time was a bewildering discovery: the world I’d entered in no way resembled the one of my childhood conception. And, as bewildering, the role I’d set myself up to play, based in commerce and convention — in this much ruder, rougher, cynical, uncinematic world — contained neither of the things I ended up needing most, which were creativity and risk.

There I was, making great money at an international accounting and consulting firm, living in Manhattan, in the thick of a super-abundant social scene; with everything, supposedly, in front of me to make a fulfilling, even enviable life. Why was it then I felt increasingly anxious and in despair? And carried about a suspicion that in all but the physical sense I was engaged in a form of gradual self-mutilation? With this condition exacerbated by a lack of understanding from a beloved parent, and my own weakness, ignorance, insecurity, confusion.

And it was in the midst of this storm I found Leonard Cohen’s music. Found and grasped immediately that, more than a perfectly exquisite soundtrack to my suffering, these sounds and words could somehow help me come through. I remember those first experiences well. Alone in a room, sitting or more often lying down, listening and letting my mind unravel was the primary activity. Something done in anticipation of relief, and compelled by a purely intuitive sense that the music was functioning as a kind of cure.

And in this, by the way, I’m far from alone. Legion are the stories about the outsized role Leoanrd Cohen’s music has played for those in distress. Stories like the one told to me by a woman in a bar: how as a teenager, while in a dark-night-of-the-soul kind of way, she ventured into a blizzard to attend a Leonard Cohen concert, and was turned around by it, made okay (And how, years later, she had the opportunity to describe this experience to Leonard Cohen directly, and he replied, ”Do you mean the night it snowed?”). Stories to be found on the vast array of Leonard Cohen-related fan websites, including Here It Is, a site whose sole purpose is to collect such personal anecdotes, testaments, expressions of gratitude. Stories like the one recounted by Christopher Hitchens in his book Mortality connecting terminal illness and the increased likelihood of Leonard Cohen’s music turning up in the mail as an otherwise unprompted gift.

Something is there: in the bare, honest, intrepid voice; the lamenting, mysterious, romantic, at times oddly rejoicing lyrics; the oft-austere, never showy arrangements. Something that at the very least harmonizes extraordinarily well with psychic dissonances; and at most, for some, if they possess the Leonard Cohen gene, induces an outright religious feeling. One all the headier for its universalist and literary qualities, but also the uniqueness of its source: a popular culture figure, somehow both playing the popular culture game and standing outside it, engaged in a seemingly authentic contemporary struggle between the sacred and profane.

Certainly, during my hard time, all of the above were at play. But also something else, which had to do with my only listening to the first three albums — Songs of Leonard Cohen, Songs From a Room, Songs of Love and Hate — which are the most pained, wrenching, raw of his catalogue. These, when listened to in a focused manner, first song to last, reliably brought about the kind of reaction Aristotle attributed to Attic tragedy; that is, a feeling of purging and catharsis, for having both experienced and escaped a fate worse than my own!

Certainly, during my hard time, all of the above were at play. But also something else, which had to do with my only listening to the first three albums — Songs of Leonard Cohen, Songs From a Room, Songs of Love and Hate — which are the most pained, wrenching, raw of his catalogue. These, when listened to in a focused manner, first song to last, reliably brought about the kind of reaction Aristotle attributed to Attic tragedy; that is, a feeling of purging and catharsis, for having both experienced and escaped a fate worse than my own!

So then, yes, adolescent attachment — of course don’t mess with it. But is it this alone twisting me out of shape? No. Probably not.

Theory #2: Rug Pull

The Leonard Cohen I thought I knew was an ambitious artist. Early on, while still in his 20s and well before he turned to music, he was a serious and flamethrowing Canadian poet in the romantic tradition; and like the romantics he esteemed, his aspirations appeared anything but modest. Indeed, evidence of this — and a first rate riff in its own right — is something Cohen is reported to have said about his dear friend and fellow flamethrowing Canadian poet, Irving Layton:

“I taught him how to dress and he taught me how to live forever.”

Was I wrong to take this more or less at face value? Especially when combined with a motif I remembered Cohen often bringing up in interviews, wherein he would describe himself as being a “minor” artist — minor in that he knew he was not a William Shakespeare or Homer, but a rung below, a Percy Bysshe Shelley or John Keats, that felt about where he was hanging, or at least trying to hang. This implied a great insight, I thought, about the nature of artistry overall — that ultimately there are three types of practitioners: Major, Minor, Biodegradable. But also, by extension, that if Cohen gave such thought to rank and stature, and saw himself in or near the strata wherein a major perk would seem to be that your name and work live on, that this same might hold attraction for him.

So I was surprised by what I read in Rolling Stone. And somewhat embarrassed, if only to myself, in the way one can get when exposed for being less the expert one thought on a topic of passion and interest.

And this, I think, along with my adolescent ties, makes a good start at untangling my present feelings; and puts me in view of what I’d like to think is inside these feelings, at their root.

Theory # 3: What We Talk About When We Talk About Leonard Cohen

Put simply: it’s up there, in the heights, among the best our culture has produced in the last 50 years. And I’m not referring to the two novels, both published in the ’60s and still in print, which were ambitious, well reviewed, and retain their contingent of champions. Nor to the poetry, Cohen’s original calling, and a form he’s never stopped working in, both for the purpose of song lyrics as well as stand alone works; he is in fact on most lists of Canada’s major poets, and in recent years his verse has even begun to appear in The New Yorker. No, it’s the music I’m of course referring to, which has proved to be his most penetrating and popular means of expression.

Thirteen studio albums, 135 or so songs, released over the course of 44 years. Hardly a prolific rate of output — Cohen has a famously laborious process — but then again how can care, patience, resistance to commercial pressure, and the evident life lived around and between these efforts be held against him? Especially when the end result is large enough that it spins out and looms like its own solar system?

Starting with Songs of Leonard Cohen. A debut made at the ripe age of 32, here is the best advertisement I know for artists exploring new forms, especially at the moment in Cohen’s development that he did: a confluence wherein he was in early maturity as a man and artist, yet retained the youthful arrogance and iconoclasm upon which he and so many young creatives first draw.

Sonically, the elements of the songs are familiar enough. A bare male voice out front, accompanied by strings, mostly guitar. After this, though, we’re onto new ground. First, with the largely unmodulated arrangements, and recurring, hypnotic circularity to the guitar playing. Also though, with the quality of the singing voice — lacking mellifluousness, yes, like many singer-songwriters, but infused with a willful courage, intelligence, utterly disarming honesty. But most of all, with the lyrical content; the storytelling, or better, mythologizing effect a song can have. Because here is a song cycle that contains just enough that is ordinary — a platonic encounter in “Suzanne,” a tenderhearted chance meeting in “Sisters of Mercy” — but otherwise treads far, far, beyond. Abounding, for example, with religious imagery; lonesome wanderings; suicidal meditations; erotic power plays; and, no small part of the magic, the almost-but-not-quite-discernible. Rendered all in what meets the ear as finely pitched poetry.

The result is real estate, opened up for and around the listener.

And with the procession of albums, though they vary dramatically in style and tone, came a deepening and enrichment of this space. Certainly it has always been capable of nurturing far more than adolescents in crisis, as I was when I first got hooked. And really, here is the key. Contained in these recordings is a full literature for adults of a certain bent. Those who gain something essential of themselves when they pass through modern life’s deep and shadowy ravines — and all the more so when their guide is the right kind of priestly, worldly, hungry, humorous, humble; and possessed by a deft poetic gift.

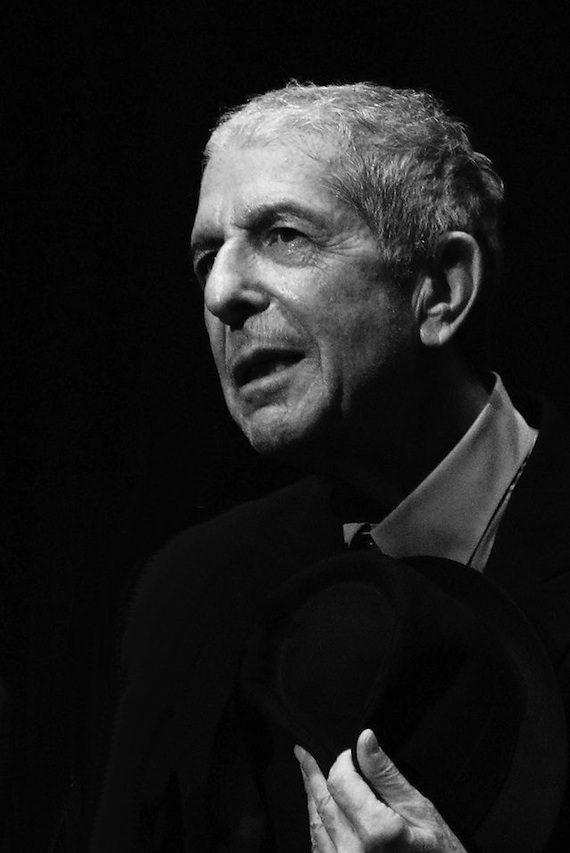

Then there are the live performances, where all this can be encountered and experienced in three dimensions. This from his first tour in 1970, to his most recent, an extended series conducted between 2008 and 2013. And while, for the pre-2008 shows, I’m compelled to rely on written accounts, for the latter my source is first hand. I attended three shows, and here again religious themes must be employed. Leonard Cohen the performer literally on his knees for large portions of the evening, evincing reverence, effusive in his gratitude, and enacting a communion with the audience evidenced most tangibly among the latter in the form of tears.

Theory #4: Altruism

This is more of an anti-theory.

Because one thing I’m pretty certain not at play in my upset, in the stake I feel in Leonard Cohen’s posterity, is altruism. That is, when I ponder the possibility that future generations will neither listen to Cohen’s music nor know his name, the feeling I’m left with is largely indifference. A shame, I’m aware, as a do-gooder angle would certainly play well. Would certainly be an easy and dare I say fashionable way through this self-examination.

Why am I sharing this? I’m not at all sure. It could be in the spirit of Leoanrd Cohen himself, the absolute value he places on truth telling in his work. And/or it might be more pragmatic. As in I just need to get this confession out of the way so I can get back to more promising ideas.

Theory #5: What We Talk About When We Talk About Leonard Cohen — Part II

It matters who makes the art. We may like to think otherwise. That in our consideration the creator and creation can be kept separate. But the more we enjoy a song, picture, story, movie, the more our imaginations seek out the biographical. And what we find informs our connection, especially over time.

And so here is Leonard Cohen, who does far better than most in this regard.

Starting with the figure he cuts today, and has for the last many years. The always well-attired gentleman with an aura that is part ageing artiste, part Old Testament sage, part retired high-level Hollywood fixer. A man who in interviews speaks thoughtfully, incisively, playfully, at times elusively about his life, career, spiritual pursuits, reputation as sexual gourmand, decades-long struggle with depression (a struggle from which in his early 70s he emerged victorious). Indeed, it’s hard to imagine someone encountering the contemporary Leoanrd Cohen in interview or profile, or for that matter the most recent biography, and not come away more favorably disposed.

Yet really this seems so for all the figures he’s cut: aging-but-still-trenchant cult figure of the ’80s and ’90s, whose musical activities were significantly curtailed by depression and spiritual pursuits, including a five-year residency in a Zen Buddhist monastery. A-list supporting player in the ’60s and ’70s zeitgeist — an always fierce but decidedly non-Aquarian voice whose friendships, adventures, liaisons connected him to the likes of Joni Mitchell, Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan, Nico, Lou Reed, Andy Warhol, Brigitte Bardot, Robert Altman, Judy Collins, Leonard Bernstein, Janis Joplin, and the Chelsea Hotel.

Before this, the serious writer living on a Greek island, pushing boundaries with literary narrative and obscenity laws on a regimen of sun, acid, barbiturates, fasting, family life with a Norwegian woman and her young son.

Preceded by Montreal, where Cohen grew up and found himself before the age of 20 the junior member of a school of like-minded artists; a group amped up on poetry, bohemian ideals, friendship, swinging the first axes at Canada’s still petrified cultural milieu.

So, wow, a bio that actually holds the light; that is, among other things, posterity-worthy. And, I realize, whether I like it or not, enforces my attachment to the man, and enriches my enjoyment of his music.

Theory #6: Me, Me, Me

True, also, it occurs in all this there might be some measure of ego involved — mine in particular.

That really, what is fandom anyway, if not an extension of self into the wider world? A blinking light of identity — and the bigger the fan the brighter the shine — wired to what one holds of great value? Worth defending? Getting really, really pissed off over?

And through this association a kind of contract is struck. With the fan, in exchange for a chunk of their identity, getting certain rights, namely to partake in the object of their fandom’s success, honor, recognition, glory. With some not-so-fine print stipulating a further condition: that the fan also suffers their object’s failures, dishonor, slights, nasty crap people post about it online.

Yes, absolutely, and the details of the relationship matter. That is, how long has it been going on between the fan and the object of their fandom? And where exactly was the object when the two first got together?

And while in my situation I’m not claiming to be the equivalent of the first shmoe in Memphis to say Hey, that Presley guy might actually have something, I have been a Leonard Cohen fan for over 25 years. And got on board when he was still a relatively obscure figure. Still prompted a lot of “Leonard who?” And to many who had heard of him, he was still something of a punch line. Misunderstood and underappreciated, even by his ostensible friend Leon Wieseltier, whose 1988 profile in The New Yorker was titled “The Prince of Bummers,” and ignored almost completely the spiritual dimension of Cohen’s work, person, appeal…

So where was I?

Right — ego, mine, and that old playground saw: you mess with my guy and you mess with me…

Theory #7: Beautiful Losersville

Confession: I can’t really recommend Leonard Cohen’s second novel, Beautiful Losers. Oh, it has its merits — supercharged intimacy and urgency, smart hipster philosophy, and an underlying scheme that successfully co-locates the personal, political, and spiritual planes of modern life. Nonetheless, I find the narrative somewhat quickly bogs down. That the acid, amphetamines, and still-youthful mysticism the influence of which he significantly wrote it under are a bit too much on display; while things like coherence, economy, restraint — all guiding values of his music — are nowhere to be found. Creating, all things considered, an effect wherein the mad visions and esoteric riffs tend to go on and on, the plot not so much.

Confession: I can’t really recommend Leonard Cohen’s second novel, Beautiful Losers. Oh, it has its merits — supercharged intimacy and urgency, smart hipster philosophy, and an underlying scheme that successfully co-locates the personal, political, and spiritual planes of modern life. Nonetheless, I find the narrative somewhat quickly bogs down. That the acid, amphetamines, and still-youthful mysticism the influence of which he significantly wrote it under are a bit too much on display; while things like coherence, economy, restraint — all guiding values of his music — are nowhere to be found. Creating, all things considered, an effect wherein the mad visions and esoteric riffs tend to go on and on, the plot not so much.

Still, I can’t overstate the importance of this novel to me — this for the title alone.

Beautiful Losers does it for me. The phrase itself. I can hardly think of one I find more brilliant and expressive, apposite for the beat and bankrupt but still somehow divine world I see around me. Or, for that matter, a phrase that works at once as taxonomy, sanctification, a cold hard fact.

And though I don’t recall the precise moment I encountered it, I know it was in my late 20s, which is to say toward the end of my adolescence. This also being several years after I’d gone AWOL on the life I’d stepped into out of college. Several years after recognizing how important engagement with art was for my survival, I had begun to do some writing myself. What an impression this juxtaposition — at least to my American ears! — made. How well it meshed with my own increasingly mashed up ideas on matters large and small, including the various things a person might end up becoming, want to become, the tricked-out words ‘losing’ and ‘winning’ themselves. And, if only implicitly, what validation that my struggle to find a way to live had been worth it. The pleasure I derived evidence that one of the unforeseeable rewards of becoming your self is the capacity to find society, with people as in ideas.

And here again I’m not alone. The term having become a fairly steady seller in pop culture vernacular — found today on t-shirts, tattoos, graffiti, the title of a band, a semi-recent documentary, countless pieces of journalism, miscellaneous communiqués in countless languages. While, at the same time, maintaining heightened resonance for people like me. A coinage acknowledged as being exceptionally representative of a Leonard Cohen state of mind. And that also, it occurs, may still have applications yet unexplored. I’m thinking in particular of something I referenced earlier, the singular space Cohen’s music evokes. That if it were ever to become an actual habitat, a locale perhaps for “the Leonard Cohen afterlife” Kurt Cobain requests in his song “Pennyroyal Tea,” Beautiful Losers might again find use. Would serve well, for example, as a password at the border. Or motto on the currency. Or, in slight variation, a pretty good name of the entire thing.

Theory # 8: The Ghost of Good Scenes Future

But then again, I might have been too hard on myself.

Earlier, when I stated that my emotional connection to Leoanrd Cohen, and in particular the stake I feel in his posterity, has nothing to do with altruism. This might not be altogether true. Which I appreciate. Because while I came away from the prior theory forced to concede I was a thoroughly selfish bastard, now I can reconsider, and make a case that it’s only partially so.

The commonweal — there is an aspect about which I most definitely care: I want there to be good scenes.

And by “scenes” I mean in the sense that gained currency in the ’60s. Counterculture slang, prompted in part by the advent of LSD, verbalizing a sense that had for decades been making its way to the fore: the way we experience our lives has become so influenced by the stories we consume — especially from movies and TV — that for accuracy’s sake, when describing life’s de facto fundamental unit, we may as well employ the corresponding term. Scenes then being what we actually get, a seemingly (but not) endless supply; our lives at any given moment, and especially in retrospect, the net sum of their quality.

And I say, good scenes for one and all.

What qualifies? Perhaps the best definition relies upon a criterion once used to legally define hardcore pornography; that is, we know it when we see it. Because for sure there are as many definitions on the planet as there are actors. Nonetheless, as a baseline, it can perhaps be said that all good scenes involve connection, even when we are by ourselves. Also this: a temporary suspension of what seems to make life a burden, and the sensation, for however long it lasts, that we are getting what we need.

And here is where Leonard Cohen comes in. Because without his music, an entire genre of good scene is in jeopardy. A genre whose basic nature should by now be evident. And, not incidentally, a genre whose best days may still lie ahead — in the rapidly approaching time of outer space habitation. A time when the near-incomprehensible distances between celestial bodies will find their way into the relations between people, with corresponding quotients of loneliness, alienation, drooping and tattered human hearts. A time, in other words, in which Leonard Cohen’s music will find optimal purchase, really make a difference, absolutely pack a punch.

Skeptical?

Well, imagine there’s this guy. A nice enough fellow for a dumb cluck, he’s living far from the world we now occupy, in some down-market solar system, on some outer planet’s moon, waiting for a sunrise that’s been weeks on the come. More, this confused young fellow, say about 25, has time on his hands, having recently quit his job trading rocket fuel futures. And psychically too he feels somewhat, no, very much in flux. Is going through that thing when for the first time in our lives we acknowledge certain truths. For example, how little we know, or control, and therefore how uncertain is our future. That thing when we start to feel fate differently. Feel fate, that is, as something that might truly, quickly, unapologetically, no-joke-at-all run us over; or maybe worse, leave us behind. With this depressing our young man, but also, strangely, leaving him in a state of wonder, and open, even hungry to let in more.

And just then a beam of light appears. The new day’s first. And he puts on some Leonard Cohen. What song? It almost doesn’t matter, as countless in the catalogue would do the trick, get him on his way into deep good scene. And yet, there’s one in particular, one Leonard Cohen song I’m thinking of, that might do even more. That is, take him through and clear a good scene. To whatever might come next.

Image Credit: Wikipedia