Early in Denis Johnson’s ninth novel, The Laughing Monsters, protagonist Roland Nair describes the odor of disinfectant in an African hotel room as assuring guests, “‘all that you fear, we have killed.’” As the recent Ebola panic has reaffirmed, few places are more fraught with dread in the Western imagination than this continental hot zone, a screen onto which the developed world’s most chronic apprehensions and misapprehensions are projected.

Africa in this gripping, demented novel is the ultimate “unknown unknown” of Rumsfeldian reckoning, teeming with the most virulent strains of viruses and extremism. Yet it’s also a theater of operations where the Chinese are pursuing strategic advantage and the full might of the U.S. intelligence machine has been mobilized to pursue shadows — as often as not its own.

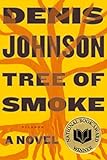

Seven years after taking on military intelligence in the National Book Award-winning novel Tree of Smoke, Johnson returns to the subject once again. But The Laughing Monsters is a much slighter affair, a fizzy alcopop compared to that kaleidoscopic work’s dark, bitter brew. Still, it leaves a poisonous aftertaste and grapples with existential queries far above its pay grade — questions of grace, theodicy, and unknowability.

Seven years after taking on military intelligence in the National Book Award-winning novel Tree of Smoke, Johnson returns to the subject once again. But The Laughing Monsters is a much slighter affair, a fizzy alcopop compared to that kaleidoscopic work’s dark, bitter brew. Still, it leaves a poisonous aftertaste and grapples with existential queries far above its pay grade — questions of grace, theodicy, and unknowability.

Leave it to Johnson, variously hailed as a visionary in the Blakean mold and a “junkyard angel,” to twist the slender frame of the “spy thriller” into a shape that can bear such hefty cosmic freight. Indeed, much of the novel’s charm lies in its disregard for the limitations of the genre. By breaking all the rules, The Laughing Monsters becomes something new — a seriocomic spy novel that’s both timely and universal.

Just as the novel is no conventional thriller, Nair is no conventional international man of mystery. He’s a crazy patchwork of identities, divided loyalties, and conflicts of interest, a spook expert in laying fiber-optic communication cables who’s also dabbled in drugs and diamonds. Equal parts dissipated opportunist and vulnerable coward, he’s inflamed above all with a lust for “cheap adventure,” whoring and buccaneering his way across the continent.

The book opens with his arrival in Freetown, Sierra Leone, where he’s arranged to meet his friend and erstwhile partner in crime, Michael Adriko, for unspecified but likely ignoble reasons. A war orphan turned U.S. black-ops commando, Adriko is a winning, exuberant shyster, nonchalantly lethal and constitutionally incapable of straight answers. He and Nair scored big here in the wake of 9/11, and have returned in hopes of “exploiting the riches of this continent.” While Nair is ostensibly doing the bidding of NATO intelligence, he’s also selling state secrets, an act of treason involving the unwitting complicity of his fiancée.

Adriko has plans of his own. His cover story is that he’s come back to marry his fiancée in the Congo. There’s also a scheme afoot to peddle precious material in Uganda — not diamonds or gold, but uranium, the ne plus ultra of mythological anxieties in this age of global terror.

This being Africa — and a Johnson novel, no less — things rapidly fall apart. Nair drinks himself into raptures, whores with unprotected abandon, muses on the maddening idiosyncrasies of the continent, has looping, antic conversations with a psychologically unraveling Adriko, and falls into the throes of an ill-considered, all-consuming passion for Adriko’s fiancée. While Tree of Smoke described a slow, tortuous spiral from idealism into disillusion and criminality, The Laughing Monsters is a zipline that starts off in amorality and zooms straight into the maw of hell.

And yet it’s all great fun, as the characters haplessly careen through a jumble of tribal affiliations and enmities, languages and creeds, ghosts and legends, made all the more incoherent by the legacy of colonial meddling. Nothing in the setting evades Johnson’s anthropological gaze: not the clocks without hour hands, the slogans on the “huge devouring face(s) of the oncoming truck(s),” nor the 100 milliliter pocket-sized pouches in which liquor is sold. It’s a place of constant power outages, where the population is strung along on the empty promise of American-style consumer culture and a listless fatalism rules the roads, with traffic playing a game of vehicular Russian roulette “as if some superstition required it.”

Though it leavens the horror, the manic, cavalier tone in which the madness is catalogued rings the odd off-note. On the other hand, Johnson’s vision isn’t easy to dismiss as smug postcolonial rubbernecking. Having traveled widely in West Africa during the early ’90s, chronicling the Liberian civil war for Esquire and The New Yorker in all its phantasmagoric brutality — cannibalism, televised tortures and executions of heads of state, addled guerillas in blonde glamour wigs and orange floatation vests supposedly endowed with the talismanic power to stop bullets — Johnson knows of what he speaks.

His Africa is a nightmare you can no more wake up from than you can look away from, in part because its nightmarishness so precisely mirrors what outsiders have done, and continue to do, to it. Though the horrors of imperialism have given way to the lesser evils of corporate plundering and western military adventurism, the result is no less toxic: a witch’s brew of political instability and rage that breeds terrorism as surely as oil spills lead to cancer. Adriko and Nair collide head-on with this vicious circle when they bog down in the Congo, their jeep swallowed by a blood-red gumbo that’s an obvious metaphor for many a recent U.S. quagmire. Later, they come face to face with the monster the developed world’s depredations have unleashed, finding themselves in the middle of a hallucinatory uprising in a stretch of the Congolese bush devastated by oil and mining operations.

For all its apparent chaos, imperviousness to reason, and resemblance to a bad trip, however, Africa as it’s depicted in The Laughing Monsters is no match for the magical thinking and folly of the U.S. intelligence apparatus.

One of the book’s chief delights lies in the way Johnson combines a satirist’s eye for absurdity with a completist’s mastery of trade craft — the gadgetry, the jargon, the cat-and-mouse of interrogation, the cagey posturing of officialdom — to paint a withering picture of the post-9/11 intelligence complex. This is the bloated, hydra-headed monstrosity of neocon dreams, “an expanded version of the old Great Game,” waging a disinformation campaign against its own people in a bid to impose the Manichean certitudes of the Cold War on a much murkier geopolitical reality. It gins up boogeymen only to get entangled in its own lies. Everyone knows it, but no one cares because everyone is getting rich. As one U.S. official admits, “Since nine-eleven, chasing myths and fairy tales has turned into a serious business. An industry. A lucrative one.”

Nair characterizes this state of affairs as “poker-faced, soft-spoken pandemonium.” That word, “pandemonium,” with its demonic etymology, is a telling one. Johnson, a self-identified Christian writer, ever alert to parallels between the political and the religious, likens the intelligence complex to a kind of false god or demiurge that casts a spell of collective madness on the populace.

All of this is narrated at an unflagging, headlong, and often disorienting clip. Though Johnson’s prose is more pared down here than in earlier novels, a current of lyrical transcendentalism runs through even the ghastliest circumstances. Beggars seem to “look through your own eyes and down your throat.” A drunk man is described as “speaking in tongues, his feet didn’t touch the floor, he was just being lugged around by his smile.”

Such verbal flourishes are not the stock stuff of spy novels, and Johnson seems content to dispense with the realism typical of the genre in favor of a pervasive, magic-drenched atmosphere of disorientation, one that captures the whirl of the African continent. The same dervishing aesthetic carries over to the novel’s structure, which juggles first-person narration, journal entries, and letters. For the most part, Johnson is dexterous enough to handle this intertextual game gracefully. But occasionally, the story vaults forward and then has to back and fill, generating a befuddling kind of whiplash.

In the end, though, neither the novel’s eccentricities of structure, nor an outlandish climactic showdown that pulls more symbolic than narrative weight, are enough to sink this unhinged foray into the heart of darkness. Though by no means a major work, The Laughing Monsters is a deceptively ambitious novel, straining toward — and sometimes achieving — transcendence. Along the way, Johnson shows that, when it comes to killing our fear of Africa, disinfectants and covert operations might have the wrong foe in their sights. As Nair says, “there’s always something more to be rid of. Something inside.”