This past March I was sitting on a stool at my local sports bar, waiting for a sandwich and daydreaming about the local team and my son’s alma mater, the Wisconsin Badgers, playing their way into the NCAA finals. (It’s amazing how much loyalty writing four years of tuition bills can instill.) I wasn’t paying much attention to the women’s basketball game on the screen until I noticed the Nebraska coach. I looked closer, and sure enough, I realized I knew the woman in the business suit, standing on the sidelines, directing the Cornhuskers. Actually, I didn’t really know Connie Yori. But I remembered her well.

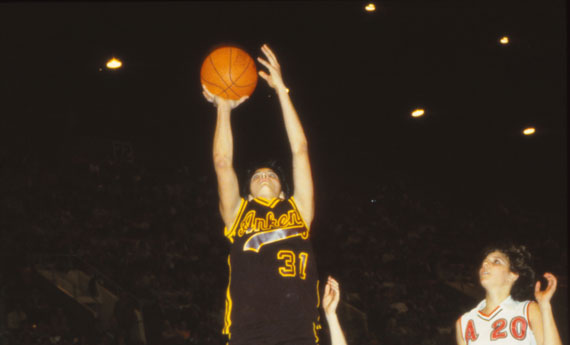

In 1981, I’d watched her throw down 49 points in the Iowa state tournament quarter-finals against Charles City, on the way to leading her Ankeny team into their second consecutive state tournament finals. Girls basketball back then was huge in Iowa. The girls state tournament routinely outsold the boys basketball tournament and the top players were legitimate state celebrities. Like Indiana back in Hoosiers (the movie) days, there was only one big tournament — none of this modern division stuff.

Connie Yori was the best girls basketball player I’d ever seen live. Five-ten, with an honest-to-god, NBA-style jump shot. She seemed to get along famously with her teammates and middle-aged coach, although at the end of practice she’d regularly ask him the same question.

“How about letting us play some five-on-five?”

He never, to my experience, relented. Because in Iowa, the game that the state was wild about was six-on-six. It was illegal for players to cross the center line. Not like “over-and-back.” Ever. Three girls played all-time defense, three played offense. Dribble three times, and it was a travel. Hold the ball for more than three seconds, turnover. They’d been playing these rules since the ’40s, and it created a major uproar when they finally switched to standard rules in 1994.

I’d started following the Ankeny girls team in the fall of 1980, introducing myself to the coach, getting permission to visit the occasional practice and scrimmage. I took a lot of pictures.

That summer, I’d called the editor of The Iowan magazine, proposing a feature story giving an inside look into this sporting phenomenon by doing a “season on the brink” — following a girls basketball team from first practice to last game.

“Okay,” the editor said, unenthusiastically. “Just don’t spend too much time on it.”

I knew what he meant. I was writing regularly for The Iowan and I knew to expect the normal payment, in the low three figures. An extra hundred if I provided the photos, which I certainly planned on doing. I wasn’t discouraged. For me, it would be an adventure, and surely a stepping stone to my dream job on the staff of Sports Illustrated.

I began looking for the right team, one within reach of my home base in Ames, Iowa, where the large city high school had no tradition of girls basketball. Girls basketball in Iowa had been the province of small-town Iowa, all the way back to its earliest days, when the basket was a peach basket and, on the rare occasion when a player managed to throw the lop-sided ball inside, a broomstick was required to knock it free.

Growing up in Iowa, even in Dubuque, where the only girls high school sports were tennis and golf, girls basketball was part of the culture. Each spring the TV broadcasts from the capacity crowds at the state’s largest arena in Des Moines took over one of the three stations our antenna received, and it was largely from these games that I learned the names of small town Iowa: Grundy Center, Montezuma, What Cheer.

I can’t recall a single boys high school player from my childhood outside my hometown, but remember watching in awe as Denise Long of Union-Whitten knocked down 111 points against Daws in the 1968 state tournament. The Des Moines Register, a paper that everyone in state seemed to get, joined in the fun when she was later drafted in the 13th round in 1969 by the NBA’s San Francisco Warriors in a publicity stunt. Women’s college basketball wasn’t even in the picture and wouldn’t be for another decade.

After considering Story City, to the north of Ames, I decided on Ankeny, a city of 15,000 south of Ames, north of Des Moines. The first time I introduced myself to coach Dick Rasmussen, he seemed a bit leery of the idea of a young reporter following his team all year, but as we chatted he came around.

“You ought to see them play softball,” he said. It was only years later than I checked the record book. The basketball girls all played on his softball team as well, winning the previous three state championships.

I had stumbled onto an unusually talented group of athletic girls, under the direction of one of Iowa’s legendary coaches. He would later say that Connie Yori, the star of that 1981 team, was the best basketball player he’d ever coached. I would be surprised if she wasn’t.

It was a bit odd, at first, watching the three-on-three girls format, especially the somewhat awkward exchanges over the center line from the defensive team to the offensive one. The two dribble rule also made the game pass-centric, if somewhat stuttering. When a team made a basket, a referee hustled the ball to mid-court to a waiting colleague where it was snapped to the offensive player stationed inside the center circle. The result was a fast-paced game, with the number of offensive possessions close to double typical in standard rules and some prodigious offensive statistics. The six-on-six rules were wildly popular in Iowa and Oklahoma. For most of the rest of the country, organized interscholastic girls basketball just didn’t exist and wouldn’t take hold until Title IX’s impact in the mid-’70s, which in 1981 was still just beginning to reshape girls and women’s sports.

The history of six-on-six rules is a bit obscure. It’s hard, with basketball such a huge business these days, to imagine the days when it a casual gymnasium PE activity with a wide variety of fluid rules, like the odd game of capture the flag or kickball. At one time, the court was divided into three areas — one for offense, one for defense, and a center area where two players did a jump ball after every score. That form of basketball was not destined for prime time. Whatever the exact details, it’s clear that the intent of six-on-six was to limit full-court running, which was felt to be too taxing for members of the fairer sex. In fact, this same sentiment was behind the demise of girls basketball in larger Iowa cities, where the belief that sports would damage young women gathered more support than in the smaller farming communities, where it was probably pretty self-evident that hard work was not the cause of widespread female health problems.

In her history of Iowa girls basketball, From Six-on-Six to Full Court Press (Iowa State University Press, 1993), Janice Beran cites anti-basketball advocates stating that competitive basketball fostered “aggressive…unladylike” characteristics. They apparently found plentiful medical experts who believed athletics affected menstrual cycles and the capacity to have children. She quotes a Scientific America article from 1926 which stated, “It may be a good thing that women are not as interested in athletics for feminine muscular development interferes with motherhood.”

In her history of Iowa girls basketball, From Six-on-Six to Full Court Press (Iowa State University Press, 1993), Janice Beran cites anti-basketball advocates stating that competitive basketball fostered “aggressive…unladylike” characteristics. They apparently found plentiful medical experts who believed athletics affected menstrual cycles and the capacity to have children. She quotes a Scientific America article from 1926 which stated, “It may be a good thing that women are not as interested in athletics for feminine muscular development interferes with motherhood.”

But despite its dodgy conceptual roots, I grew to enjoy the frequent passing, the ability of a single player to dominate the offensive game, the frustration of teams trying to double-team Yori, only to have her slip passes to her teammates, one of whom would go on to be a Division 1 collegiate basketball guard for Drake. You might say it was the original triangle offense. Yori, unlike the stars of just a decade earlier, had the opportunity for athletic scholarships and inter-collegiate play. She ended up in Omaha, at Creighton, where she became a mainstay among the top scorers in collegiate basketball.

The 1981 team dominated the regular season and played into the state finals for the second year in a row. The Iowan got me a press pass and it was my first, and only, visit to the tournament. The scene at Veteran’s Auditorium for the state tournament was, pardon the cliché, electric. The place was sold out and raucous. The boys from these small schools seemed to be unabashed fans, the younger kids, face painted in school colors, gave it a carnival atmosphere. I remember chatting with a young Congressman courtside, Chuck Grassley, who was wearing a shiny suit with a wide tie displaying a gigantic knot. He seemed to be having a grand time, meeting and greeting folks in preparation for the launch of his 30-plus-year career in the U.S. Senate.

Sports Illustrated was covering the event and had installed flashes in the rafters of the gym, so that its photographers could get perfectly lit photos of the action. I pushed my black and white film setting and shot with a blurry, wide-open aperture, sitting on the floor courtside with all the pro shooters with larger, faster lenses. It was a close contest, with Ankeny losing the game on a final-second basket by Norwalk, reversing the two-point win over Norwalk Ankeny had scored in the finals the previous year. I still have a roll of film shot from the basketball floor after the buzzer, where I, only somewhat shamefully, roamed, capturing the hugs and tears.

Four years later, the tournament was broken into two divisions as larger schools joined the Title IX sports revolution. The larger schools played five-on-five, while the smaller schools continued with the old format. These two styles co-existed uncomfortably until 1993, when Atlantic beat Montezuma. The following year, the tournament was split into four divisions, based on enrollment, and they all played by standard modern rules.

As for my career as a sports writer, I did, that winter, cover a professional tennis tournament in Chicago for World Tennis Magazine. I watched the Chicago press corps grumble about the free sandwiches they were fighting for, two old rivals, who seemed like grandpas to me, almost coming to blows. They asked the players ridiculous questions in the press conference, including one reporter wondering if John McEnroe feared being shot by a fan. Another reporter went on a tirade because the tournament changed the order of an evening’s program, after he’d gone to press, turning him “into a liar.”

That was end of my short, happy life as a sports reporter, and close to the end of my days in Iowa. I never covered another basketball event as a writer, and soon moved away, never to return. That’s made my season on the brink all the more memorable and special. When I think fondly of my home state, in my mind, the three girls on the offensive team are still out there on the hardwood, in their black kneepads, waiting at center court for a defensive rebound and a chance to move the ball, two steps at a time, towards the goal.