1.

I saw an interesting conversation on Twitter the other day. A book critic I know was struggling with the question of how to convey, without being a jerk about it, the unfortunate truth of the book she was reviewing: it was too much like too many other books, which is to say, written in a style she referred to as “standard-issue MFA.” Someone came up with the impressively diplomatic “technically proficient, but never quite rises beyond the realm of the expected.”

I disagree with the reviewer’s implied dismissal of MFA writers, but I knew what she meant. I read a lot of books that are too much like other books. My personal belief is that American publishers have a tendency to over-publish, and that there would be a little less mediocrity out there if the focus were to shift in the direction of smaller lists with better marketing support. But, on the other hand, it’s possible that the existence of a vast realm of the expected in literature is inevitable. By definition, obviously, only a few of anything in any given category are going to be exceptional. Most drivers are only average drivers; most lawyers are only average lawyers; most books are only average books.

Still, though. Setting the matter of inevitability aside, the sea of expectedness can wear on a person. Books arrive on my doorstep almost daily. Almost all of them are perfectly competent, writing-wise, and all are heralded by their respective publicists as something excellent and truly unusual. The books arrive faster than I can read them, an ever-rising tide of padded envelopes. Of the ones I do find the time to read, I write reviews of perhaps one in 10, and it isn’t because the other nine are of such shattering brilliance that I find myself dumbstruck.

It’s because competence isn’t enough. Like almost every other reader I know, I am always searching for books that aren’t like other books. I want to read the books that aren’t standard-issue anything.

2.

2.

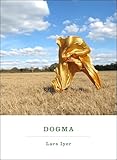

Lars Iyer has written three novels to date, a trilogy, and they are entirely unlike anything else I’ve ever read. Spurious, Dogma, and Exodus are concerned with a years-long conversation and a peculiar friendship between two British philosophy lecturers: Lars (“Not to be confused with me,” the British author and lecturer in philosophy Lars Iyer said at a reading in Manhattan last year) and fictional Lars’s friend and tormentor, W. (not to be confused with the non-fictional Lars’s real-life friend and tormentor, W., non-fictional Lars said.)

The Lars and W. of these books are on an endless quest for meaning, for one truly original thought, for a leader, for better gin. But all of these things are secondary to the central tragedy of their lives, summed up beautifully in Exodus:

Oh, he has some sense of what we lack, W. says. More than I have, but then he’s more intelligent than I am. He has some sense that there’s another kind of thinking, another order of idea, into which one might break as a flying fish breaks the surface of the water. He knows it’s there, the sun-touched surface, far above him. He knows there are thinkers whose wings flash with light in the open air, who leap from wave-crest to wave-crest, and that he will never fly with them.

Iyer’s books, Drew Nellins wrote in a review of Dogma on this site last year, are “certainly not for everyone. In fact, I fear that relating to these characters might be a warning — the fading canary in the mental health coal mine.”

This seems disconcertingly possible. I’ve pushed these books on various friends and family members, with admittedly mixed success. Lars and W. take it as a given that end times are upon us, that almost no one cares about great thinkers or great thought, and that civilization is on the verge of collapse, if it hasn’t in fact collapsed already. The books have a peculiar, almost dreamlike rhythm. Very little actually happens. The first, Spurious, was very funny, in a the-world-is-ending-but-let’s-go-find-some-better-gin kind of way:

W. remembers when I was up and coming, he tells me. He remembers the questions I used to ask, and how they would resound beneath the vaulted ceilings. —’You seemed so intelligent then’, he says. I shrug. ‘But when any of us read your work…’, he says, without finishing the sentence.

By Dogma, a much darker current had risen to the surface. An acquaintance of mine wrote in an email that he found it quite different from Spurious: “Less funny, more incantatory, maybe more paranoid. By the time I got to the end of it, I felt like it was almost some bizarre book of Revelations.”

There were funny moments in Dogma, a few, but there were also a great many lines like these: “His crops have failed, W. says, as they have always failed, and he stands in the empty field, weeping.” And: “It’s time to die, says W. But death will not come.”

“We need novels forged in the black fire of despair,” Lars Iyer said, in an interview at Full Stop a year and a half ago. “Personal despair, political despair, even cosmic despair. Novels shot through with a sense that the end is nigh, that all our efforts are in vain, but that we might at least laugh at our predicament. Laugh — but with a laughter as black as the forces that we laugh at.”

3.

In Exodus, Iyer strikes a less despairing tone. The world is still ending, obviously, and capitalism has mangled the academy beyond recognition, but the quest for meaning continues. Lars and W. long as always for revelation. (“‘Go on, say something profound,’ W. says to the plenary speaker.”)

Lars (the fictional Lars; I’m in no position to comment on the real one) came late to academia. He was unemployed for a long time, years, and also there was a long period when he worked in a warehouse. There are moments when W., remembering this, considers Lars with a kind of awe:

What vacancies I have known! What boredoms! What diffuse despairs! The everyday still clings to me like bits of shell to a hatching chick, W. says. It’s why, in the end, he has a kind of respect for me. For isn’t the everyday the contemporary equivalent of the Biblical desert?

I read this passage twice, fold the page so I can find it again, draw a little star in the margin.

4.

4.

While we’re on the topic of the desert of the everyday, let’s briefly give the floor to David Foster Wallace. In The Pale King, an instructor in taxation addresses a class of future IRS agents:

“Gentlemen,” he said, “…here is a truth: Enduring tedium over real time in a confined space is what real courage is. Such endurance is, as it happens, the distillate of what is, today, in this world neither I nor you have made, heroism. Heroism.”

5.

But if it takes a certain courage to withstand the everyday — the hassles, the lines, the tedium of your job, that recorded voice insisting unconvincingly that your call is very important to us, the Muzak, the stalled subway trains, the car with the dead battery, etc. — surely it takes considerably more courage to refuse to surrender to it, to insist on searching for meaning even at the personal risk of looking ridiculous, perhaps even to insist on a modicum of grace. Enduring the everyday is relatively straightforward — just keep breathing and putting one foot in front of the other — but how to transcend the everyday, in this world neither you nor I have made?

It’s a pressing question, both in general and in Exodus, where W. and Lars are up against the enemies of thought and teetering on the cliff-edge of unemployment in a world that’s come to view the study of philosophy with indifference, if not outright hostility. Humanities departments are being gutted. W., in fact, is the sole survivor of the philosophy department at his institution, owing to some obscure legal technicality that’s rendered him immune to layoffs. He has been reduced to teaching badminton ethics to sports science students who arrive in class with towels around their necks.

His colleagues wear tracksuits to work, and have whistles around their necks, W. says on the phone. He can see them doing star-jumps outside his window. He finds it oddly hypnotic, he says. It soothes him when he looks up from his reading.

Things are no better at Lars’s university. Lars’s university is a construction zone. (“They’re rebuilding the campus, I tell W. They’re putting up new office blocks for the private partners of the university.”) Trees are being shredded to make way for corporate offices. There are trucks everywhere. Construction continues day and night. The racket is relentless. It’s very difficult to concentrate. Obviously, the only reasonable short-term solution is a lecture tour. But civilization as they know it is changing just as obviously in the cities as it is on campus:

Manchester’s completely changed, I tell W., as we walk from the station. I hardly recognize the place. When did it happen? How did it happen?

We must have been asleep. We must have forgotten that the world was changing. We’ve been outflanked, we agree. Outrun.

We’ve all been outflanked, really. There was a time when books were much more central to the culture than they are now. How to transcend the everyday? Excellent literature helps. Exodus is an elegant and beautifully-written conclusion to a wholly original trilogy.