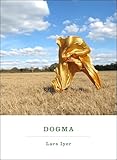

Dogma is the second in a projected trilogy by Lars Iyer. Like its predecessor, Spurious, this book is surreal, brainy, plotless, and arguably pointless. It is also brilliantly written and very funny. The only problem is that, in wondering who else might enjoy it, I couldn’t think of anyone I know to whom I could give an unqualified recommendation. True, that might suggest something about the kind of people I hang around with, but I can’t help noticing that it suggests something about these books too. They’re certainly not for everyone. In fact, I fear that relating to these characters might be a warning — the fading canary in the mental health coalmine.

Dogma is the second in a projected trilogy by Lars Iyer. Like its predecessor, Spurious, this book is surreal, brainy, plotless, and arguably pointless. It is also brilliantly written and very funny. The only problem is that, in wondering who else might enjoy it, I couldn’t think of anyone I know to whom I could give an unqualified recommendation. True, that might suggest something about the kind of people I hang around with, but I can’t help noticing that it suggests something about these books too. They’re certainly not for everyone. In fact, I fear that relating to these characters might be a warning — the fading canary in the mental health coalmine.

Dogma, like Spurious, is told entirely through the interactions of Lars and W., a pair of philosophy lecturers and writers locked in a strange semblance of friendship. Though they live on opposite sides of England, they have frequent phone calls, visit each other, and even travel together. Sometimes W.’s girlfriend Sal is in tow, but it’s usually just the two of them, operating like a combination between Waiting for Godot and Withnail and I.

Dogma, like Spurious, is told entirely through the interactions of Lars and W., a pair of philosophy lecturers and writers locked in a strange semblance of friendship. Though they live on opposite sides of England, they have frequent phone calls, visit each other, and even travel together. Sometimes W.’s girlfriend Sal is in tow, but it’s usually just the two of them, operating like a combination between Waiting for Godot and Withnail and I.

Early on, the men embark on a lecture tour of the southern United States, and it appears for a flickering moment that the book might contain a beginning, middle, and end. Maybe character arcs too. But that plotline goes cold pretty quickly. Iyer isn’t interested in starting in one place and ending up in another. Instead of developing, his characters circle the drain — a fitting arrangement for a pair who obsess about entropy while seemingly doing their best to embody the concept.

They share an incredible inventory of obsessions: the end of the world, the connection between religion and capitalism. They love the mysterious Texan musician Jandek and the slightly less weird Texan musician Josh T. Pearson. W. can’t stop talking about Franz Rosenzweig, and frequently wonders if God’s existence can be proven through higher mathematics read in the original German. They obsess over the relationship between Kafka and Max Brod, the friend who made Kafka posthumously famous, repeatedly asking of themselves and one another which of them might be Kafka to the other’s Brod. W. can’t stop talking about the Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr, and, in particular the film Werckmeister Harmonies.

This isn’t merely a list of preoccupations. They’re practically fetishes, ground to be covered again and again. Repetition is somehow key to Iyer’s project. When the men decide to start a new intellectual movement of somewhat unclear underpinnings and call it “Dogma,” W. devises the rules and then repeats them, revising and elaborating on them. The effect of so much repetition is that the sequence of the book — which is divided into many small sections of just a few pages each — is all but irrelevant. Dogma reads almost like a collage, a fitting style for a book more concerned with philosophy than narrative.

Ideas drive everything. Lars and W.’s biggest fear is that they are cursed with the ability to recognize and appreciate important intellectual contributions, but are unable to make significant contributions of their own. Or — somewhat more poignantly — they fear they’ve actually had their great ideas and forgotten them, or that their great ideas passed in conversation without either of them realizing it. The reader is put in the position of wondering the same thing as he reads. Have I missed the point in all this?

Iyer employs the first-person perspective with fantastic flair and originality. The narrator, Lars, reveals himself almost exclusively through the words of his friend and says practically nothing about himself directly. It would be challenging, if not impossible, to find a page in Dogma which does not contain the words “W. says.” This narrative choice is especially interesting given that W.’s primary mode of communication with Lars is scathing criticism, of his weight, his clothes, this apathy, his failure to do good work or to think deeply. In a late scene, W. wishes for Lars to join him at a meeting with his employers, with whom he has developed an adversarial relationship. “Why not take a lawyer, I ask him. He’s allowed to. No, he wants the equivalent of an idiot child, W. says. He wants the equivalent of a diseased ape with scabs round his mouth throwing faeces around the room….Did you see who he had with him?, they’ll say. What he had with him? My God, we shouldn’t make his life any worse: that’s what they’ll say, W. says. And perhaps then they’ll show mercy.” Relentless and very funny, the abuse never seems to bother Lars, who receives it in a state of either bemusement or agreement — it’s never clear which.

When, years ago, Roger Ebert reviewed W.’s favorite movie, Werckmeister Harmonies, he described it as “maddening if you are not in sympathy with it, mesmerizing if you are.” It’s a perfect characterization of Dogma’s protagonists. “We’ve become strange, W. says. We’ve spent too much time in each other’s company… We’re no longer fit for human society, W. says.” He’s almost right, I’m afraid. But not quite. I don’t know who else might like this strange book as much as I did, but, as for me, I can’t wait for the third.

Previously: Mold, Gin, and the Apocalypse: Lars Iyer’s Spurious