Even back in the mid-eighties, my mother referred to the Eastowne Mall as Ghost Town Mall, though whether that was an established nickname or something she made up, I don’t know (my guess is the former). The mall’s primary feature was the Eastowne 5, a movie theater that at the time showed first-run films and during my middle-school years functioned as a prime makeout spot. I kissed a girl for the first time there, during 18 Again!, a switch comedy starring George Burns and Charlie Schlatter. Switch comedies were in vogue then. In addition to 18 Again!, you had Vice Versa (Judge Reinhold–Fred Savage) and Like Father Like Son (Dudley Moore–Kirk Cameron). I kissed the same girl some months later, during Big, but my memory is that Tom Hanks’ character magically grows up overnight instead of switching identities with a kid. I may be wrong about that; it’s been a long time since I’ve seen it.

Across from the Eastowne 5 was the Final Curtain, a cavernous restaurant and bar with a large screen on the wall overhead that showed classic movies and whose second floor housed a mysterious nightclub called Legends; next to that was the Bop Stop, a used record store run by a friendly, knowledgeable, chain-smoking gentleman named John; and at the end of that wing, tucked in the corner, was Abbey Road Books. Aside from the large, fluorescent-lit Perry Drug Store — the Eastowne anchor store, so to speak — located halfway down the mall, many of the remaining stores were vacant.

I spent a lot of time at Abbey Road Books waiting for movies to start, and on one occasion made a special trip for an event: a book signing featuring Rich Hall of Not Necessarily the News and Sniglets fame. I believe this was in the summer of 1986. I was a fan of the show and especially of Sniglets, a segment that highlighted “any word that doesn’t appear in the dictionary, but should.” Per the show’s suggestion, I’d sent in a list of my own made-up words hoping they’d land on TV or in one of the Sniglets books, and the cosmic silence that greeted my submission was perhaps the first writer-rejection I encountered. I don’t remember what my Sniglets were, but the definition of one of them had to do with sticking your toothbrush under a strong-running tap and losing your freshly applied toothpaste. It seemed a phenomenon that required naming.

Rich Hall was the first celebrity I ever saw up close. As he was led into the store (at which few people had gathered) I grew instantly nervous. It was shocking to see someone from TV in person, and I was mute as I handed him my copy of Unexplained Sniglets of the Universe for signing. He may or may not have asked my name to personalize it; I may or may not have said “Bryan,” and then shyly added “with a y”; he may or may not have scrawled the date. In time I came to feel retrospectively bad for Rich Hall, trudging through the Ghost Town Mall to an ill-attended event at an out-of-the-way bookshop to be descended upon by a quivering twelve-year-old. This was long before I’d suffered through my own dismally attended readings, hoping that whoever was there wouldn’t hear the disappointment in my voice as I thanked them for coming and began my spiel.

Rich Hall was the first celebrity I ever saw up close. As he was led into the store (at which few people had gathered) I grew instantly nervous. It was shocking to see someone from TV in person, and I was mute as I handed him my copy of Unexplained Sniglets of the Universe for signing. He may or may not have asked my name to personalize it; I may or may not have said “Bryan,” and then shyly added “with a y”; he may or may not have scrawled the date. In time I came to feel retrospectively bad for Rich Hall, trudging through the Ghost Town Mall to an ill-attended event at an out-of-the-way bookshop to be descended upon by a quivering twelve-year-old. This was long before I’d suffered through my own dismally attended readings, hoping that whoever was there wouldn’t hear the disappointment in my voice as I thanked them for coming and began my spiel.

Abbey Road Books was necessarily windowless; it had thick shag carpet (possibly orange); in my memory there’s a narrow balcony area, a kind of second floor, that housed more books; on a shelf behind the cash-register counter was the sleeve for the Beatles record after which the store was named. One day I was browsing there and saw a book with a title I knew well: Fast Times at Ridgemont High. It had Sean Penn as Spicoli flanked by two babes on the cover. I had seen the movie somewhat recently on third-generation video and thanks largely to the nudity was an enthusiastic devotee. Initially I didn’t think much about the book. I assumed it was a movie tie-in (though I wouldn’t have used that phrase) and placed it back on the shelf. But as the days passed I found myself brooding over it, wanting to take another peek. At some point I returned to Abbey Road and looked again, now fully intrigued. I read the back, flipped through it, read scattered passages.

I didn’t have the money to buy it so I put it back. But in the days that followed I thought of it often, to the point of fixation, finally deciding that I had to have it. It was an early (maybe the first) instance of a phenomenon that has become quasi-routine: encountering a book, acknowledging it with little interest (perhaps even dismissing it, deciding I’ll never read it), setting it down again, exiting the store, thinking about it some more, returning to the store later to examine it more closely, reading the first few pages, setting it down again, leaving the store again, engaging in further reflection, thinking about it as I go about my daily life, determining at last that I must acquire it at all costs ($5.95 for Fast Times, which, by the way, is a true story, the product of Cameron Crowe’s year of deep-cover reporting at a California high school).

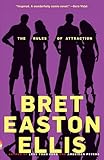

Another book that caught my eye at Abbey Road was Bret Easton Ellis’ second novel, The Rules of Attraction. I knew I wanted this one right away — I’d seen the movie of Less Than Zero twice and was obsessed with it. I had also read the book, a movie tie-in version with the cast on the cover that I stole from the paperback rack at Perry Drugs. Reading it was disorienting, since, as you may know, the film version doesn’t resemble the novel in the least (Ellis is fond of saying that not one line of his novel ended up in the movie, though this isn’t entirely accurate: the graffito Julian gives great head. And is dead appears in both, though the movie has it on the wall of a beach condo and not a club bathroom in Encino). But it was easy to read, I liked the style, and in addition to making me want to blow my mind on cocaine, it acted as a model for some of my earliest stabs at fiction — there was a bleak piece of stripped down, druggy prose called “Screw” (I stole the title from a Cure song; from the start I was an unapologetic thief).

Another book that caught my eye at Abbey Road was Bret Easton Ellis’ second novel, The Rules of Attraction. I knew I wanted this one right away — I’d seen the movie of Less Than Zero twice and was obsessed with it. I had also read the book, a movie tie-in version with the cast on the cover that I stole from the paperback rack at Perry Drugs. Reading it was disorienting, since, as you may know, the film version doesn’t resemble the novel in the least (Ellis is fond of saying that not one line of his novel ended up in the movie, though this isn’t entirely accurate: the graffito Julian gives great head. And is dead appears in both, though the movie has it on the wall of a beach condo and not a club bathroom in Encino). But it was easy to read, I liked the style, and in addition to making me want to blow my mind on cocaine, it acted as a model for some of my earliest stabs at fiction — there was a bleak piece of stripped down, druggy prose called “Screw” (I stole the title from a Cure song; from the start I was an unapologetic thief).

The Rules of Attraction cemented my interest in Ellis. I wrote to him that year as part of an English-class project in which we sent letters to our favorite authors. He didn’t write back. Eighteen years later I saw him at the PEN Gala at the Museum of Natural History in New York. He walked by me on the way to the men’s room. I heard him say to someone, “Nice to see you.” I was on edge being at such a fancy event among so many famous writers and had drunk too much free alcohol in an attempt to unwind. I wondered what Ellis would do if I followed him into the bathroom and, as he was excreting, told him of my youthful fandom and the letter I sent. In the letter I’d asked why he dedicated Less Than Zero to Joe McGinniss, whose true-crime tome Fatal Vision had been a source of dark fascination to me in fifth grade — again, after watching the made-for-TV movie adaptation starring Gary Cole and Karl Malden. Somehow I acquired the book, and my consuming interest in it — I drew a large picture of an ice pick dripping blood, and tried to arouse my classmates’ interest in the tale of family slaughter — prompted a concerned call home from school.

Abbey Road Books closed in the late eighties, never to return. The Bop Stop moved out to Portage. Perry Drugs closed. The Eastowne 5 started showing second-run movies for a dollar. Somehow — insanely — the Final Curtain hung in there, but eventually it too disappeared. Then the theater closed, and the mall itself nearly ceased to exist before receiving a minor, ineffective facelift along with a new name: Gull Crossing. You will not find a Banana Republic or Williams-Sonoma there. But you will find a small movie theater now called the Gull Road Cinema 5.

The theater reopened in 2004. Almost a decade before that, when it was still the Eastowne 5, I went there with my girlfriend Margie. We bought tickets to see The Firm and sat in the last row making out the whole time, barely glancing at the screen. This had been a planned act. It was my idea. I was trying to do what they say can never be done — go home again or recapture the past or whatever. The movie was based on a book, of course, which many years later I read and loved.

Image by Karla Wozniak, courtesy of Gregory Lind gallery