1. The Revelation of St. Arbitron

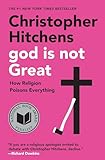

“And behold, a door was opened, and I heard a voice saying, ‘In the name of Zarathustra and Inherit the Wind and the H.M.S. Beagle, I will cleanse thee of ignorance and iniquity.’ And I looked, and a throne was set atop the bestseller list, and on this throne sat Richard Dawkins, bearing in his right hand The God Delusion. And a great cry went up throughout the land, yea, even unto the last airport bookshop. Then I saw a beast rise up out of the sea, having ten horns and seven cigarettes, and upon his cigarettes seven flames, and upon his horns ten copies of God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, and verily, this was the one called Hitchens. The four angels of radio, print, television, and blog rested not day and night, saying, ‘Holy, holy Hitch; the great day of his wrath is come.’ And he spake many hard words before going away to the green room of Charlie of Rose to sup on sandwiches of watercress and await the final victory.”

“And behold, a door was opened, and I heard a voice saying, ‘In the name of Zarathustra and Inherit the Wind and the H.M.S. Beagle, I will cleanse thee of ignorance and iniquity.’ And I looked, and a throne was set atop the bestseller list, and on this throne sat Richard Dawkins, bearing in his right hand The God Delusion. And a great cry went up throughout the land, yea, even unto the last airport bookshop. Then I saw a beast rise up out of the sea, having ten horns and seven cigarettes, and upon his cigarettes seven flames, and upon his horns ten copies of God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, and verily, this was the one called Hitchens. The four angels of radio, print, television, and blog rested not day and night, saying, ‘Holy, holy Hitch; the great day of his wrath is come.’ And he spake many hard words before going away to the green room of Charlie of Rose to sup on sandwiches of watercress and await the final victory.”

So, at any rate, apostles of secularism might recall the mid-Aughts a century from now. Those pre-Crash years also saw the publication of blockbuster critiques of religion by cognitive theorist Daniel C. Dennett (Breaking the Spell) and neuroscientist Sam Harris (Letter to a Christian Nation). By the spring of 2007, when the distinguished British philosopher A.C. Grayling brought forth Against All Gods, a collection of “polemics against religion,” a movement—or at least, a cool name for one—had emerged: “The New Atheism.” But aside from a genre-defining profile in Wired Magazine, the New Atheism was written about more often than well, obscuring the really interesting question. What, aside from a common subject and a serendipity of publication dates, bound these writers together? What exactly made the New Atheism new?

So, at any rate, apostles of secularism might recall the mid-Aughts a century from now. Those pre-Crash years also saw the publication of blockbuster critiques of religion by cognitive theorist Daniel C. Dennett (Breaking the Spell) and neuroscientist Sam Harris (Letter to a Christian Nation). By the spring of 2007, when the distinguished British philosopher A.C. Grayling brought forth Against All Gods, a collection of “polemics against religion,” a movement—or at least, a cool name for one—had emerged: “The New Atheism.” But aside from a genre-defining profile in Wired Magazine, the New Atheism was written about more often than well, obscuring the really interesting question. What, aside from a common subject and a serendipity of publication dates, bound these writers together? What exactly made the New Atheism new?

One answer was, simply, the temperature of its rhetoric. Gone was the hedged irony of Voltaire, the allegorical grandeur of Nietzsche, the urbane agnosticism of Bertrand Russell; from titles onward, truculence was the order of the day. (Particle physicist Victor J. Stenger’s God: The Failed Hypothesis: How Science Shows That God Does Not Exist, from 2007, surely deserves a special place in the annals of unsubtlety.) Gone, too, was the Grand Bargain biologist Stephen Jay Gould had proposed in the mid-‘90s: that science and religion coexist as “non-overlapping magisteria.” For Hitchens, a semi-pro talk-show guest, disagreeing to disagree may have been a point of pride. But for Grayling, an ethicist, it was a matter of principle. For too long, he argued, liberal tolerance had thrown a “diaphanous veil” over religion’s most illiberal drives—toward dogma, toward repression, toward conquest and sectarian violence. Dawkins was even more explicit: “As long as we accept the principle that religious faith must be respected simply because it is religious faith,” he wrote, “it is hard to withhold respect from the faith of Osama bin Laden.”

One answer was, simply, the temperature of its rhetoric. Gone was the hedged irony of Voltaire, the allegorical grandeur of Nietzsche, the urbane agnosticism of Bertrand Russell; from titles onward, truculence was the order of the day. (Particle physicist Victor J. Stenger’s God: The Failed Hypothesis: How Science Shows That God Does Not Exist, from 2007, surely deserves a special place in the annals of unsubtlety.) Gone, too, was the Grand Bargain biologist Stephen Jay Gould had proposed in the mid-‘90s: that science and religion coexist as “non-overlapping magisteria.” For Hitchens, a semi-pro talk-show guest, disagreeing to disagree may have been a point of pride. But for Grayling, an ethicist, it was a matter of principle. For too long, he argued, liberal tolerance had thrown a “diaphanous veil” over religion’s most illiberal drives—toward dogma, toward repression, toward conquest and sectarian violence. Dawkins was even more explicit: “As long as we accept the principle that religious faith must be respected simply because it is religious faith,” he wrote, “it is hard to withhold respect from the faith of Osama bin Laden.”

To the New Atheists’ credit, their anti-jihad jihad was an interfaith affair, targeting not only bearded Wahabbists but Orthodox Israeli settlers and Bible-thumping televangelists. Hitchens derided the Bush Administration for “want[ing] to hand over the care of the poor to ‘faith-based’ institutions,” even as he bolstered the anti-Islamist case for its wars in Greater Petrolia. Dawkins warned of a “Christian Taliban” in the U.S.

Today, though, the religious foment that seemed just a few years ago to be a species-level threat looks more like random variation in a global evolution toward unbelief. Barack Obama may have been the first U.S. presidential candidate to have to leave his church in order to be elected. Gay marriage just became legal in New York. Osama bin Laden is dead, and the largely secular character of the Arab Spring has muted talk of a Second Caliphate abroad. The Great Economic Stagnation has, give or take a few mosques, redirected our attention from cultural quiddities to our credit-card statements. If a turn toward fundamentalism were truly the alpha and omega of the New Atheist story, we might expect the latter to have run its course.

Instead, it’s proven strangely durable; witness such recent titles as The Divinity of Doubt and The Christian Delusion and The Belief Instinct and The Religion Virus and Against All Gods (no relation), not to mention Stenger’s The New Atheism and Harris’ The Moral Landscape and Hitchens’ The Quotable Hitchens and Philip Pullman’s The Good Man Jesus and The Scoundrel Christ. How to square this abundance of supply with the dwindling of demand? A solution appears when we turn to what is in many ways the most ambitious and interesting of these second-wave works, Grayling’s The Good Book: A Humanist Bible. It is, surprisingly, that the New Atheism’s quarrel isn’t really with God after all.

Instead, it’s proven strangely durable; witness such recent titles as The Divinity of Doubt and The Christian Delusion and The Belief Instinct and The Religion Virus and Against All Gods (no relation), not to mention Stenger’s The New Atheism and Harris’ The Moral Landscape and Hitchens’ The Quotable Hitchens and Philip Pullman’s The Good Man Jesus and The Scoundrel Christ. How to square this abundance of supply with the dwindling of demand? A solution appears when we turn to what is in many ways the most ambitious and interesting of these second-wave works, Grayling’s The Good Book: A Humanist Bible. It is, surprisingly, that the New Atheism’s quarrel isn’t really with God after all.

2. Bringing Down the Velvet Hammer

To the fine art of sacrilege, Grayling brings a lighter touch than Dawkins, the New Atheism’s Cardinal Newman, or Hitchens, its Torquemada. (“I’m the velvet version,” Grayling has said.) Where God is Not Great was content to assert that “The serious ethical dilemmas are better handled by Shakespeare and Tolstoy…than in the mythical morality tales of the holy books,” The Good Book aims to demonstrate it. That is, rather than pump out another polemic, Grayling has “conceived selected redacted arranged worked and in part written” a huge and entirely God-free compendium of what the poet Matthew Arnold called “the best that has been thought and said,” from Plato to Cato, from the Metamorphoses to The Origin of Species.

To the fine art of sacrilege, Grayling brings a lighter touch than Dawkins, the New Atheism’s Cardinal Newman, or Hitchens, its Torquemada. (“I’m the velvet version,” Grayling has said.) Where God is Not Great was content to assert that “The serious ethical dilemmas are better handled by Shakespeare and Tolstoy…than in the mythical morality tales of the holy books,” The Good Book aims to demonstrate it. That is, rather than pump out another polemic, Grayling has “conceived selected redacted arranged worked and in part written” a huge and entirely God-free compendium of what the poet Matthew Arnold called “the best that has been thought and said,” from Plato to Cato, from the Metamorphoses to The Origin of Species.

This would be a major intellectual achievement in its own right. Owning The Good Book is like having the entire Western Canon on Shuffle (or, depending on your place in the culture wars, being stuck with The White Man’s Greatest Hits). And it’s possible to treat it not as an argument at all, but as a desk reference… or even a cheap alternative to freshman year of college.

Still, there’s a distinctly New Atheist provocation in Grayling’s decision to format his diverse sources in the manner of that other “Good Book.” A one-man Council of Nicea, he has arranged his source material thematically, scrubbed it of attributions, rendered prose into numbered and vaguely iambic verse, and filled in gaps with his own transitional passages. The seams are nearly invisible. What we see instead are fourteen cohesive “books,” with titles like “Proverbs,” “Acts,” and “Parables.” Grayling’s ambition, clearly, is not just to secularize religious accounts of the human condition (à la the Jefferson Bible); it’s to supplant them.

How successful is he? It may be useful to think back to the criteria for belief systems William James laid out a century ago in The Varieties of Religious Experience (still the best book you’re likely to find on the subject of faith.) By James’ first measure, “philosophical reasonableness,” The Good Book blows most scripture out of the water. “The forces underlying everything” in its “Genesis” are the empirically verifiable laws of physics and biology. The apple in this garden is Newton’s. And the scientific account of creation leaves little room for the repressions and mystifications of monotheism. No Adam’s rib, no original sin, and no hang-ups about the body and its urges:

How successful is he? It may be useful to think back to the criteria for belief systems William James laid out a century ago in The Varieties of Religious Experience (still the best book you’re likely to find on the subject of faith.) By James’ first measure, “philosophical reasonableness,” The Good Book blows most scripture out of the water. “The forces underlying everything” in its “Genesis” are the empirically verifiable laws of physics and biology. The apple in this garden is Newton’s. And the scientific account of creation leaves little room for the repressions and mystifications of monotheism. No Adam’s rib, no original sin, and no hang-ups about the body and its urges:

If an individual should be presented to another of the same species and of a different sex,

Then the feeling of all other needs is suspended: the heart palpitates, the limbs tremble;

Voluptuous images wander through the mind

It’s interesting that heterosexism should persist even here, but Grayling’s commitment to objectivity helps dilute it. (Later, in “Acts,” he’ll handle the ancient Greek practice of pederasty with nary a blush.) At any rate, it’s hard to imagine The Good Book driving readers to disown family members on account of sexual preference, or to stone to death women accused of adultery.

The Good Book comes on equally strong in James’ second category, “moral helpfulness.” When God said to Abraham, “Kill me a son,” Cicero’s argument against vice in the name of loyalty (paraphrased in a section called “Concord”) might have come in handy. And to the New Testament’s ethic of judgment (“Whosoever doeth not righteousness is not of God”), The Good Book counterposes the urbane empathy of Walter Pater:

Not to recognize, every moment, some passionate attitude in those about us, and in the brilliancy of their gifts some tragic dividing of their ways,

Is, in life’s short day of frost and sun, to sleep before evening.

Is virtue possible in the absence of brimstone and damnation? In fact, as the title suggests, a coherent philosophy of virtue is The Good Book’s signal accomplishment.

Grayling’s scriptural ambitions, however, impose on the text a split personality. At any given moment, it speaks with the wise man’s Apollonian serenity. In the exhaustive and exhausting aggregate, though, The Good Book starts to seem anxious that no one’s listening. This anxiety comes to the fore in the penultimate chapter, “Epistles,” which takes the form of father-to-son letters and reads like Hamlet, if Hamlet were a two-hour monologue by Polonius. Over and over, the writer warns his son that “jokers,” distractions, and “weak minds” are all around. We begin to hear echoes of the other New Atheists: of Harris’ attack on “moral relativism;” of Dawkins’ intolerance for semi-believers and Possibilitarians; of Hitchens’ call for “A New Enlightenment.” What elevates “stronger minds” above the masses, in The Good Book, is faith in a very particular strain of the humanist tradition. In fact, that faith is what united the New Atheists all along.

3. Forever and Ever, A Meh…

“Humanism,” as Grayling circumscribes it, is pragmatic, rationalist, and skeptical only in a narrow, scientific sense. The great pessimists and naysayers who haunt Western philosophy appear here and there in The Good Book—a soupçon of Hume in “The Lawgiver,” a dollop of Schopenhauer in “Lamentations.” (Interestingly, these are where the book comes closest to achieving James’ third criterion, “immediate luminousness.”) But in its basic outlines Grayling’s humanism is that of the nineteenth-century positivists, who built a philosophy around their belief in the perfectability of human nature. For Grayling, and for the other New Atheists, reason doesn’t just answer questions about our origins and our ethics; it moves us toward that city on a hill where, The Good Book promises, “the best future might inhabit, and the true promise of humanity be realized at last.”

But expressed this nakedly, the vision seems Whiggish, even naïve. And certainly outdated. For four centuries after Copernicus uncentered the Earth, reason was on the march, claiming more and more of the territory previously arrogated to religion. In the fields of biology and cosmology and paleontology, angels rushed out wherever wise men dared to tread. (Grayling, alone among the New Atheists, has emphasized this historical long view: “Today’s ‘religious upsurge,’ is a reaction to defeat, in a war that it cannot win.”) More recently, though, various experiments in the sphere of culture—laissez-faire economics, Politburo politics, literary Deconstruction—have suggested that irrationalism persists, or even thrives, where religion has been elbowed aside. (A Good Book-style anthology limited to the post-1960s period would echo Ezekiel, by way of the Byrds: “overturn, overturn, overturn.”)

To the beleaguered humanist, the hard sciences of the 21st Century offer scant consolation. Indeed the great boom-discipline of the age—neuroscience—suggests that where reason exists, it is, no more or less than its opposite, a mere byproduct of electricity and chemistry, a ghost in the machine. The New Atheists make various attempts to countenance this; in this way they are cousins of the modish authors of Blink and Proust Was a Neuroscientist and The Wisdom of Crowds. Harris goes so far as to suggest, in The Moral Landscape, that brain-imaging studies may lead to a new science of morality. So far, though, Neurobiological Man so far bears little resemblance to the rational paragon of the humanist imagination.

To the beleaguered humanist, the hard sciences of the 21st Century offer scant consolation. Indeed the great boom-discipline of the age—neuroscience—suggests that where reason exists, it is, no more or less than its opposite, a mere byproduct of electricity and chemistry, a ghost in the machine. The New Atheists make various attempts to countenance this; in this way they are cousins of the modish authors of Blink and Proust Was a Neuroscientist and The Wisdom of Crowds. Harris goes so far as to suggest, in The Moral Landscape, that brain-imaging studies may lead to a new science of morality. So far, though, Neurobiological Man so far bears little resemblance to the rational paragon of the humanist imagination.

Moreover, the humanists’ triumphal account of scientific history focuses on the Newtons and Darwins while overlooking the folks tinkering in the lab. Herbert Marcuse long ago pointed out the patent irrationality of the world order to which such tinkering, in the form of the atomic bomb, gave rise. And in the information technologies currently transforming our lives, applied science has allowed us to redraw the line between fact and belief, offering the body politic an inoculation against scientific consensus. On comment-threads and twitter feeds, Arnold’s “ignorant armies” can clash ad infinitum. Evidence is whatever we can Google. No wonder the New Atheists feel like an aggrieved minority.

“The truth explains everything,” runs one of Grayling’s “Proverbs.” It’s an article of faith for these writers. But they must sense, even as they affirm it, that the real threat to the cult of human reason in the 21st Century is not the religious, but epistemological. We live today under the dispensation of what one contemporary wise man calls “truthiness.” In the great ecumenical marketplace of our culture, belief systems thrive not on compulsion, or verifiability, but on narrative interest. This helps explain why, with better-defined enemies in disarray, the air has started to leak from the New Atheist balloon—why Dawkins’ forthcoming riposte to J.K. Rowling, The Magic of Reality, sounds so distinctly un-magical, and why Grayling’s Good Book, laudable in its aspirations, is ultimately more fun to think about than to read.

“The truth explains everything,” runs one of Grayling’s “Proverbs.” It’s an article of faith for these writers. But they must sense, even as they affirm it, that the real threat to the cult of human reason in the 21st Century is not the religious, but epistemological. We live today under the dispensation of what one contemporary wise man calls “truthiness.” In the great ecumenical marketplace of our culture, belief systems thrive not on compulsion, or verifiability, but on narrative interest. This helps explain why, with better-defined enemies in disarray, the air has started to leak from the New Atheist balloon—why Dawkins’ forthcoming riposte to J.K. Rowling, The Magic of Reality, sounds so distinctly un-magical, and why Grayling’s Good Book, laudable in its aspirations, is ultimately more fun to think about than to read.

This is not to say that the scriptures of this particular group of unbelievers hold no interest for us. But even a half-decade on, we can see that they’ll someday seem exactly as remote—exactly as poignant—as the lapsed religions they sought to supplant. That is, the New Atheism now appears to us godless cosmopolitans like any other faith: as noble, as fallible, as wondrously, humanly, world-historically beside the point.