“Here I am writing about him again, like a vicious old man who promises that this will be the last drink of his life.” – Horacio Castellanos Moya

I.

If you’ve been tooling around the cross-referential world of Anglo-American literary blogs this fall, chances are you’ve come across an essay from the Argentine paper La Naçion called “Bolaño Inc.” Back in September, Scott Esposito of Conversational Reading linked to the original Spanish. When Guernica published an English translation this month, we mentioned it here. The Guardian followed suit (running what amounted to a 500-word paraphrase). Soon enough, Edmond Caldwell had conscripted it into his ongoing insurgency against the critic James Wood. Meanwhile, the literary blog of Wood’s employer, The New Yorker, had posted an excerpt under the title: “Bolaño Backlash?”

The basic premise of “Bolaño Inc.” – that Roberto Bolaño, the late Chilean author of the novels The Savage Detectives and 2666, has become a kind of mythological figure hovering over the North American literary landscape – was as noteworthy as it was unobjectionable. One had only to read reports of overflow crowds of galley-toting twentysomethings at the 2666 release party in New York’s East Village to see that the Bolaño phenomenon had taken on extraliterary dimensions. Indeed, Esposito had already pretty thoroughly plumbed the implications of “the Bolaño Myth” in a nuanced essay called “The Dream of Our Youth.” But when that essay appeared a year ago in the online journal Hermano Cerdo, it failed to “go viral.”

The basic premise of “Bolaño Inc.” – that Roberto Bolaño, the late Chilean author of the novels The Savage Detectives and 2666, has become a kind of mythological figure hovering over the North American literary landscape – was as noteworthy as it was unobjectionable. One had only to read reports of overflow crowds of galley-toting twentysomethings at the 2666 release party in New York’s East Village to see that the Bolaño phenomenon had taken on extraliterary dimensions. Indeed, Esposito had already pretty thoroughly plumbed the implications of “the Bolaño Myth” in a nuanced essay called “The Dream of Our Youth.” But when that essay appeared a year ago in the online journal Hermano Cerdo, it failed to “go viral.”

So why the attention to “Bolaño Inc.?” For one thing, there was the presumable authority of its author, Horacio Castellanos Moya. As a friend of Bolaño’s and as a fellow Latin American novelist (one we have covered admiringly), Castellanos Moya has first-hand knowledge of the man and his milieu. For another, there was the matter of temperament. A quick glance at titles – the wistful “The Dream of Our Youth,” the acerbic “Bolaño Inc.” – was sufficient to measure the distance between the two essays. In the latter, as in his excellent novel Senselessness, Castellanos Moya adopted a lively, pugnacious persona, and, from the title onward, “Bolaño Inc.” was framed as an exercise in brass-tacks analysis. “Roberto Bolaño is being sold in the U.S. as the next Gabriel García Marquez,” ran the text beneath the byline,

So why the attention to “Bolaño Inc.?” For one thing, there was the presumable authority of its author, Horacio Castellanos Moya. As a friend of Bolaño’s and as a fellow Latin American novelist (one we have covered admiringly), Castellanos Moya has first-hand knowledge of the man and his milieu. For another, there was the matter of temperament. A quick glance at titles – the wistful “The Dream of Our Youth,” the acerbic “Bolaño Inc.” – was sufficient to measure the distance between the two essays. In the latter, as in his excellent novel Senselessness, Castellanos Moya adopted a lively, pugnacious persona, and, from the title onward, “Bolaño Inc.” was framed as an exercise in brass-tacks analysis. “Roberto Bolaño is being sold in the U.S. as the next Gabriel García Marquez,” ran the text beneath the byline,

a darker, wilder, decidedly un-magical paragon of Latin American literature. But his former friend and fellow novelist, Horacio Castellanos Moya, isn’t buying it.

Beneath Castellanos Moya’s signature bellicosity, however, beats the heart of a disappointed romantic (a quality he shares with Bolaño), and so, notwithstanding its contrarian ambition, “Bolaño Inc.” paints the marketing of Bolaño in a pallette of reassuring black-and-white, and trots out a couple of familiar villains: on the one hand, “the U.S. cultural establishment;” on the other, the prejudiced, “paternalistic,” and gullible American readers who are its pawns.

As Esposito and Castellanos Moya argue, the Bolaño Myth in its most vulgar form represents a reduction of, and a distraction from, the Bolaño oeuvre; in theory, an attempt to reckon with it should lead to a richer understanding of the novels. In practice, however, Castellanos Moya’s hobbyhorses lead him badly astray. Following the scholar Sarah Pollack, (whose article in a recent issue of the journal Comparative Literature is the point of departure for “Bolaño Inc.”), he takes the presence of a Bolaño Myth as evidence for a number of conclusions it will not support: about its origin; about the power of publishers; and about the way North Americans view their neighbors to the South.

These points might be so local as to not be worth arguing – certainly not at length – were it not for a couple of their consequences. The first is that Castellanos Moya and Pollack badly mischaracterize what I believe is the appeal of The Savage Detectives for the U.S. reader – and in so doing, inadvertently miss the nature of Bolaño’s achievement. The second is that the narrative of “Bolaño Inc.” seems as tailor-made to manufacture media consent as the Bolaño Myth it diagnoses. (“Bolaño was sooo 2007,” drawls the hipster who haunts my nightmares.) Like Castellanos Moya, I had sworn I wasn’t going to write about Bolaño again, at least not so soon. But for what it can tell us about the half-life of the work of art in the cultural marketplace, and about Bolaño’s peculiar relationship to that marketplace, I think it’s worth responding to “Bolaño Inc.” in detail.

II.

The salients of the Bolaño Myth will be familiar to anyone who’s read translator Natasha Wimmer‘s introduction to the paperback edition of The Savage Detectives. Or Siddhartha Deb‘s long reviews in Harper’s and The Times Literary Supplement. Or Benjamin Kunkel‘s in The London Review of Books, or Francisco Goldman‘s in The New York Review of Books, or Daniel Zalewski‘s in The New Yorker (or mine here at The Millions), or any number of New York Times pieces. Castellanos Moya offers this helpful précis:

his tumultuous youth: his decision to drop out of high school and become a poet; his terrestrial odyssey from Mexico to Chile, where he was jailed during the coup d’etat; the formation of the failed infrarealist movement with the poet Mario Santiago; his itinerant existence in Europe; his eventual jobs as a camp watchman and dishwasher; a presumed drug addiction; and his premature death.

Alongside the biographical Bolaño Myth, according to Castellanos Moya and Pollack, runs a literary one – that Bolaño has replaced García Márquez as the representative of “Latin American literature in the imagination of the North American reader.”

Relative to the heavy emphasis on the biography, mentions of García Márquez are less common in North American responses to The Savage Detectives. But one can feel, broadly, the way that familiarity with Bolaño now signifies, for the U.S. reader, a cosmopolitan intimacy with Latin American literature, as, for a quarter century, familiarity with García Márquez did. And this must be irritating for a Latin American exile like Castellanos Moya, as if every German one spoke to in Berlin were to say, “Ah, yes…the English language…well, you know, I’ve recently been reading E. Annie Proulx.” (Perhaps Proulx isn’t even the right analogue. How large does Bolaño loom in the Spanish-speaking world, anyway, assuming such a world (singular) exists? I’m told Chileans prefer Alberto Fuguet, and my friend in Barcelona had never heard of him until he became famous over here.)

One can imagine, also, the frustration a Bolaño intimate might have felt upon reading, in large-circulation publications, that the author nursed a heroin addiction…when, to judge by the available evidence, he didn’t. As we’ve written here, the meme of Bolaño-as-junkie seems to have originated in the Wimmer essay, on the basis of a misreading of a short story. That this salacious detail made its way so quickly into so many other publications speaks to its attraction for the U.S. reader: it distills the subversive undercurrents of the Bolaño Myth into a single detail, and so joins it to a variety of preexisting narratives (about art and madness; about burning out vs. fading away). Several publications went so far as to draw a connection between drug use and the author’s death, at age 50, from liver disease. This amounted, as Bolaño’s widow wrote to The New York Times, to a kind of slander.

And so “Bolaño Inc.” offers us two important corrections to the historical record. First, Castellanos Moya insists, Bolaño, by his forties, was a dedicated and “sober family man.” It is likely that this stability, rather than the self-destructiveness we find so glamorous in our artists, facilitated the writing of Bolaño’s major works. Secondly, Castellanos Moya reminds us of the difficulty of slotting this particular writer into any storyline or school. “What is certain,” writes Castellanos Moya, “is that Bolaño was always a non-conformist; he was never a subversive or a revolutionary wrapped up in political movements, nor was he even a writer maudit.” This is as much as to say, Bolaño was a writer – solitary, iconoclastic, and, in his daily habits, a little boring.

III.

“Bolaño Inc.” starts to fall apart, however, when Castellanos Moya dates the origins of the Bolaño Myth to the publication of The Savage Detectives. In 2005, editors at Farrar, Straus & Giroux acquired the hotly contested rights to The Savage Detectives, reportedly for somewhere in the mid six figures – on the high end for a work of translation by an author largely “unknown” in the U.S. The posthumous appeal of Bolaño’s personal story no doubt helped the sale along.

“Bolaño Inc.” starts to fall apart, however, when Castellanos Moya dates the origins of the Bolaño Myth to the publication of The Savage Detectives. In 2005, editors at Farrar, Straus & Giroux acquired the hotly contested rights to The Savage Detectives, reportedly for somewhere in the mid six figures – on the high end for a work of translation by an author largely “unknown” in the U.S. The posthumous appeal of Bolaño’s personal story no doubt helped the sale along.

FSG’s subsequent marketing campaign for the novel would emphasize specific elements of the author’s biography. “The profiles,” a former editor at another publishing house observed, “essentially wrote themselves.” Among the campaign’s elements were the online publication of what would become Wimmer’s introduction to the paperback edition. The hardcover jacket photo was a portrait of a scraggly Bolaño circa 1975. Castellanos Moya takes this as proof positive of a top-down crafting of the Bolaño myth (though Lorin Stein, a senior editor at FSG, told me, “I stuck that picture . . . on the book because it was my favorite and because it was in the period of the novel”).

As it would with 2666, FSG printed up unusually attractive galley editions, and carpet-bombed reviewers, writers, and even editors at other houses with a copy, “basically signaling to the media that this was their ‘important’ book of the year,” my editor friend suggested. When the book achieved sales figures unprecedented for a work of postmodern literature in translation “the standard discourse in publishing . . . was was that the publisher had ‘made’ that book.” Or, as Castellanos Moya puts it,

in the middle of negotiations for The Savage Detectives appeared, like a bolt from the blue, the powerful hand of the landlords of fortune, who decided that this excellent novel was the work chosen to be the next big thing.

But here Castellanos Moya begs the question: why did these particular negotiations entice FSG in the first place? He treats the fact that the book was “excellent” almost parenthetically. (And Pollack’s article is almost comical in its rush to bypass what she calls Bolaño’s “creative genius” – a quality that doesn’t lend itself to the kind of argumentation on which C.V.s are built these days.) Then again, it might be fair to say that excellence is an afterthought in the marketplace, as well.

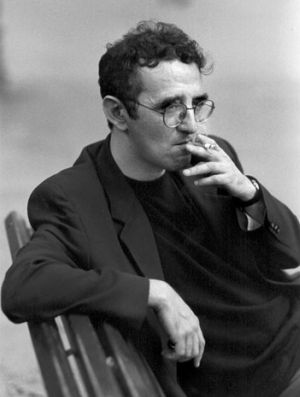

Likely more attractive for FSG was the fact that, by 2006, much of the groundwork for the Bolaño Myth had already been laid. Over several years, New Directions, an independent American press, had already published – “carefully and tenaciously,” Castellanos Moya tells us – several of Bolaño’s shorter works. New Directions was clearly not oblivious to the fascination exerted by the author himself (to ignore it would have amounted to publishing malpractice). The jacket bio for By Night In Chile, published in 2003, ran to an unusually detailed 150 words: arrest, imprisonment, death… By the following year, when Distant Star hit bookshelves, the head-shot of a rather gaunt-looking Bolaño had been swapped out for a fantastically moody portrait of the black-clad author in repose, inhaling a cigarette. These translations, by Chris Andrews, won “Best Books of the Year” honors from the major papers on both coasts, and led to excerpts in The New Yorker.

Likely more attractive for FSG was the fact that, by 2006, much of the groundwork for the Bolaño Myth had already been laid. Over several years, New Directions, an independent American press, had already published – “carefully and tenaciously,” Castellanos Moya tells us – several of Bolaño’s shorter works. New Directions was clearly not oblivious to the fascination exerted by the author himself (to ignore it would have amounted to publishing malpractice). The jacket bio for By Night In Chile, published in 2003, ran to an unusually detailed 150 words: arrest, imprisonment, death… By the following year, when Distant Star hit bookshelves, the head-shot of a rather gaunt-looking Bolaño had been swapped out for a fantastically moody portrait of the black-clad author in repose, inhaling a cigarette. These translations, by Chris Andrews, won “Best Books of the Year” honors from the major papers on both coasts, and led to excerpts in The New Yorker.

Nor can the initial development of the Bolaño Myth be laid at the feet of New Directions. Lest we forget, the sensation of The Savage Detectives began in 1999, when the novel won the Rómulo Gallegos prize, the preeminent prize for Spanish language fiction. Bolaño’s work in Spanish received glowing reviews from the TLS, almost all of which included a compressed biography in the opening paragraph.

In fact, the ultimate point of origin for the Bolaño myth – however distorted it would ultimately become – was Bolaño himself. Castellanos Moya avers that his friend “would have found it amusing to know they would call him the James Dean, the Jim Morrison, or the Jack Kerouac of Latin American literature,” and Bolaño would surely have recoiled from such a caricature. But his fondness for reimagining his life at epic scale is as distinctive an element in his authorial sensibility as it is in Philip Roth‘s. It is most pronounced in The Savage Detectives, where he rewrites his own youth with a palpable, and powerful, yearning. So complete is the identification between Bolaño and his fictional alter-ego, Arturo Belano, that, when writing of a rumored movie version of The Savage Detectives, Castellanos Moya confuses the former with the latter.

In fact, the ultimate point of origin for the Bolaño myth – however distorted it would ultimately become – was Bolaño himself. Castellanos Moya avers that his friend “would have found it amusing to know they would call him the James Dean, the Jim Morrison, or the Jack Kerouac of Latin American literature,” and Bolaño would surely have recoiled from such a caricature. But his fondness for reimagining his life at epic scale is as distinctive an element in his authorial sensibility as it is in Philip Roth‘s. It is most pronounced in The Savage Detectives, where he rewrites his own youth with a palpable, and powerful, yearning. So complete is the identification between Bolaño and his fictional alter-ego, Arturo Belano, that, when writing of a rumored movie version of The Savage Detectives, Castellanos Moya confuses the former with the latter.

At any rate, Castellanos Moya has the causal arrow backward. By the time FSG scooped up The Savage Detectives, Bolaño’s “reputation and legend” were already “in meteoric ascent” (as a 2005 New York Times piece put it) both in the U.S. and abroad. The blurbs for the hardcover edition for The Savage Detectives were drawn equally from reviews of the New Directions editions and from publications like Le Monde des Livres, Neuen Zurcher Zeitung, and Le Magazine Littéraire – catnip not for neo-Beats or Doors fanatics but for exactly the kinds of people who usually buy literature in translation. And it was after all a Spaniard, Enrique Vila-Matas, who detected in The Savage Detectives a sign

that the parade of Amazonian roosters was coming to an end: it marked the beginning of the end of the high priests of the Boom and all their local color.

A cynical reading of “Bolaño Inc.” might see it less as a cri de coeur against “the U.S. cultural establishment” than as an outgrowth of sibling rivalry within it. One imagines that the fine people at New Directions have complicated feelings about a larger publisher capitalizing on the groundwork it laid, and receiving the lion’s share of the credit for “making” The Savage Detectives. (Just as Latin American writers might feel slighted by the U.S. intelligentsia’s enthusiastic adoption of one of their own.) At the very least, it’s worth at noting that New Directions, a resourceful and estimable press, in Castellanos Moya’s account and in fact, is also his publisher.

IV.

On second thought, it is a little anachronistic to imagine that either publisher figures much in the larger “U.S. cultural establishment.” To be sure, it would be naïve to discount the role publishers and the broader critical ecology play in “breaking” authors to the public. There are even books, like The Lost Symbol or Going Rogue, whose bestseller status is, like box-office receipts of blockbusters, pretty much assured by the time the public sees them. But The Savage Detectives was not one of these. The amount paid for the book “was not exorbitant enough to warrant an all-out Dan Brown-like push,” one editor told me. “Books with that price tag bomb all the time.” And Lorin Stein noted that The Savage Detectives

On second thought, it is a little anachronistic to imagine that either publisher figures much in the larger “U.S. cultural establishment.” To be sure, it would be naïve to discount the role publishers and the broader critical ecology play in “breaking” authors to the public. There are even books, like The Lost Symbol or Going Rogue, whose bestseller status is, like box-office receipts of blockbusters, pretty much assured by the time the public sees them. But The Savage Detectives was not one of these. The amount paid for the book “was not exorbitant enough to warrant an all-out Dan Brown-like push,” one editor told me. “Books with that price tag bomb all the time.” And Lorin Stein noted that The Savage Detectives

surpassed our expectations by a long shot. How many 600-page experimental translated books make it to the bestseller list? You can’t work that sort of thing into a business plan.

I’m thinking here of Péter Nádas‘ A Book of Memories – an achievement comparable to The Savage Detectives, and likewise published by FSG, but not one that has become totemic for U.S. readers. Castellanos Moya might attribute Nádas’ modest U.S. sales to the absence of a compelling “myth.” But we would already have come a fair piece from the godlike “landlords of the market,” descending from their home in the sky to anoint “next big things.” And the sluggish sales this year of Jonathan Littell‘s The Kindly Ones – another monumental translation with a six-figure advance and a compelling narrative attached – further suggest that the landlords’ power over the tenants is erratic, or at least weakening.

I’m thinking here of Péter Nádas‘ A Book of Memories – an achievement comparable to The Savage Detectives, and likewise published by FSG, but not one that has become totemic for U.S. readers. Castellanos Moya might attribute Nádas’ modest U.S. sales to the absence of a compelling “myth.” But we would already have come a fair piece from the godlike “landlords of the market,” descending from their home in the sky to anoint “next big things.” And the sluggish sales this year of Jonathan Littell‘s The Kindly Ones – another monumental translation with a six-figure advance and a compelling narrative attached – further suggest that the landlords’ power over the tenants is erratic, or at least weakening.

Indeed, it is “Bolaño Inc.”‘s treatment of these tenants – i.e. readers – that is the most galling element of its argument. The Savage Detectives, Castellanos Moya insists, offers U.S. readers a vision of Latin America as a kind of global id, ultimately reaffirming North American pieties

like the superiority of the protestant work ethic or the dichotomy according to which North Americans see themselves as workers, mature, responsible, and honest, while they see their neighbors to the South as lazy, adolescent, reckless, and delinquent.

As Pollack puts it,

Behind the construction of the Bolaño myth was not only a publisher’s marketing operation but also a redefinition of Latin American culture and literature that the U.S. cultural establishment is now selling to the public.

Castellanos Moya and Pollack seem to want simultaneously to treat readers as powerless before the whims of publishers and to indict them for their colonialist fantasies. (This is the same “public” that in other quarters gets dunned for its disinterest in literature in translation, and in literature more broadly.) Within the parameters of the argument “Bolaño Inc.” lays out, readers can’t win.

But the truth is that U.S. readers of The Savage Detectives are less likely to use it as a lens on their neighbors to the south than as a kind of mirror. From Huckleberry Finn onward, we have been attracted to stories of recklessness and nonconformity wherever we have found them. When we read The Savage Detectives, we are not comforted at having sidestepped Arturo Belano’s fate. We are Arturo Belano. Likewise, the Bolaño Myth is not a story about Latin American literature. It is a dream of who we’d like to be ourselves. In its lack of regard for the subaltern, this may be no improvement on the charges “Bolaño Inc.” advances. But the attitude of the U.S. metropole towards the global south – in contrast, perhaps, to that of Lou Dobbs – is narcissistic, not paternalistic. Purely in political terms, the distinction is an important one.

V.

Moreover, Pollack’s quietist reading of the novel (at least as Castellanos Moya presents it) condescends to Bolaño himself, and is so radically at variance with the text as to be baffling. The Savage Detectives, she writes, “is a very comfortable choice for U.S. readers, offering both the pleasures of the savage and the superiority of the civilized.” Perhaps she means this as an indictment of the ideological mania of the Norteamericano, who completely misses what’s on the page; such an indictment would no doubt be “a very comfortable choice” for the readers of Comparative Literature. But to write of the novel as exploring “the difficulty of sustaining the hopes of youth,” as James Wood has, is far from reading it as a celebration of the joys of bourgeois responsibility.

Instead, The Savage Detectives offers a disquieting experience – one connected less to geography than to chronology. Bolaño is surely the most pan-national of Latin American writers, and his Mexico City could, in many respects, be L.A. It’s the historical backdrop – the 1970s – that give the novel its traction with U.S. readers. (In this way, the jacket photo is an inspired choice.)

Instead, The Savage Detectives offers a disquieting experience – one connected less to geography than to chronology. Bolaño is surely the most pan-national of Latin American writers, and his Mexico City could, in many respects, be L.A. It’s the historical backdrop – the 1970s – that give the novel its traction with U.S. readers. (In this way, the jacket photo is an inspired choice.)

The mid-’70s, as Bolaño presents them, are a time not just of individual aspirations, but of collective ones. Arturo and Ulises seem genuinely to believe that, confronted with a resistant world, they will remake it in their own image. Their failure, over subsequent years, to do so, is not a comforting commentary on the impossibility of change so much as it is a warning about the death of our ability to imagine progress – to, as Frederic Jameson puts it, “think the present historically.” Compare the openness of the ’70s here to the nightmarish ’90s of 2666. Something has been lost, this novel insists. Something happened back there.

The question of what that something was animates everything in The Savage Detectives, including its wonderfully shattered form, which leaves a gap precisely where the something should be. And this aesthetic dimension is the other disquieting experience of reading book – or really, it amounts to the same thing. In the ruthless unity of his conception Bolaño discovers a way out of the ruthless unity of postmodernity, and the aesthetic cul-de-sac it seemed to have led to. Seemingly through sheer willpower, he became the artist he had imagined himself to be.

VI.

This is the nature of the hype cycle: if the Bolaño backlash augured by The New Yorker‘s “Book Bench” materializes, it will not be because readers have revolted against the novel (though there are readers whom the book leaves cold) but because they have revolted against a particular narrative being told about it. And Castellanos Moya, with his impeccable credentials and his tendentious but seductive account of the experience The Savage Detectives offers U.S. readers, provides the perfect cover story for those who can’t be bothered to do the reading. That is, “Bolaño Inc.” offers readers the very same enticements that the Bolaño Myth did: the chance to be Ahead of the Curve, to have an opinion that Says Something About You. Both myth and backlash pivot on a notion of authenticity that is at once an escape from commodification and the ultimate commodity. Bolaño had it, the myth insists. His fans don’t, says “Bolaño Inc.” But what if this authenticity itself is a construction? From what solid ground can we render judgment?

For a while now, I’ve been thinking out loud about just this question. One reader has accused me of hostility to the useful idea that taste is as constructed as anything else, and to the “hermeneutics of suspicion” more generally. I can see some of this at work in my reaction to “Bolaño Inc.” But the hermeneutics of suspicion to which Castellanos Moya subscribes should not mistake suspicion for proof of guilt. Indeed, it should properly extend suspicion to itself.

It may be easier to build our arguments about a work of art on assumptions about “the marketplace,” but it seems to me a perverse betrayal of the empirical to ignore the initial kick we get from the art that kicks us – the sighting of a certain yellow across the gallery, before you know it’s a De Kooning. Yes, you’re already in the gallery, you know you’re supposed to be looking at the framed thing on the wall, but damn! That yellow!

When I revisit my original review of The Savage Detectives – a book I bought because I liked the cover and the first page, and because I’d skimmed Deb’s piece in Harper’s – I find a reader aware of the star-making machinery, but innocent of the biographical myth to which he was supposed to be responding. (You can find me shoehorning it in at the end, in a frenzy of Googling.) Instead, not knowing any better, I began by trying to capture exactly why, from one writer’s perspective, the book felt like a punch in the face. This seems, empirically, like a sounder place to begin thinking about the book than any preconception that would deny the lingering intensity of the blow. I have to imagine, therefore, that, whatever their reasons for picking up the book, other readers who loved it were feeling something similar.

Not that any of this is likely to save us from a Bolaño backlash. Castellanos Moya’s imagining of the postmodern marketplace as a site with identifiable landlords – his conceit that superstructure and base can still be disentangled – has led him to overlook its algorithmic logic of its fashions. The anomalous length and intensity of Bolaño’s coronation (echoing, perhaps, the unusual length and intensity of his two larger novels) and the maddening impossibility of pinning down exactly what’s attributable to genius and what’s attributable to marketing have primed us for a comeuppance of equal intensity.

But when the reevaluation of Bolaño begins in earnest – and again, in some ways it might serve him well – one wants to imagine the author would prefer for it to respond to, and serve, what’s actually on the page. Of course the truth is, he probably wouldn’t give a shit either way. About this, the Myth and its debunkers can agree: Roberto Bolaño would probably be too busy writing to care.

[Bonus Link: Jorge Volpi‘s brilliant, and somewhat different, take on all this is available in English at Three Percent.]