Mentioned in:

Most Anticipated: The Great Summer 2024 Preview

Summer has arrived, and with it, a glut of great books. Here you'll find more than 80 books that we're excited about this season. Some we've already read in galley form; others we're simply eager to devour based on their authors, subjects, or blurbs. We hope you find your next summer read among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

July

Art Monster by Marin Kosut [NF]

Kosut's latest holds a mirror to New York City's oft-romanticized, rapidly gentrifying art scene and ponders the eternal struggles between creativity and capitalism, love and labor, and authenticity and commodification. Part cultural analysis, part cautionary tale, this account of an all-consuming subculture—now unrecognizable to the artists who first established it—is the perfect companion to Bianca Bosker's Get the Picture. —Daniella Fishman

Concerning the Future of Souls by Joy Williams [F]

If you're reading this, you don't need to be told why you need to check out the next 99 strange, crystalline chunks of brilliance—described enticingly as "stories of Azrael"—from the great Joy Williams, do you? —John H. Maher

Misrecognition by Madison Newbound [F]

Newbound's debut novel, billed as being in the vein of Rachel Cusk and Patricia Lockwood, chronicles an aimless, brokenhearted woman's search for meaning in the infinite scroll of the internet. Vladimir author Julia May Jonas describes it as "a shockingly modern" novel that captures "isolation and longing in our age of screens." —Sophia M. Stewart

Pink Slime by Fernanda Trías, tr. Heather Cleary [F]

The Uruguayan author makes her U.S. debut with an elegiac work of eco-fiction centering on an unnamed woman in the near future as she navigates a city ravaged by plague, natural disaster, and corporate power (hardly an imaginative leap). —SMS

The Last Sane Woman by Hannah Regel [F]

In Regel's debut novel, the listless Nicola is working in an archive devoted to women's art when she discovers—and grows obsessed with—a beguiling dozen-year correspondence between two women, going back to 1976. Paul author Daisy LaFarge calls this debut novel "caustic, elegant, elusive, and foreboding." —SMS

Reinventing Love by Mona Chollet, tr. Susan Emanuel [NF]

For the past year or so I've been on a bit of a kick reading books that I'd hoped might demystify—and offer an alternative vision of—the sociocultural institution that is heterosexuality. (Jane Ward's The Tragedy of Heterosexuality was a particularly enlightening read on that subject.) So I'm eager to dive into Chollet's latest, which explores the impossibility of an equitable heterosexuality under patriarchy. —SMS

The Body Alone by Nina Lohman [NF]

Blending memoir with scholarship, philosophy with medicine, and literature with science, Lohman explores the articulation of chronic pain in what Thin Places author Jordan Kisner calls "a stubborn, tender record of the unrecordable." —SMS

Long Island Compromise by Taffy Brodesser-Akner [F]

In this particular instance, "Long Island Compromise" refers to the long-anticipated follow-up to Fleishman Is In Trouble, not the technical term for getting on the Babylon line of the LIRR with a bunch of Bud-addled Mets fans after 1 a.m. —JHM

The Long Run by Stacey D'Erasmo [NF]

Plenty of artists burn brightly for a short (or viral) spell but can't sustain creative momentum. Others manage to keep creating over decades, weathering career ups and downs, remaining committed to their visions, and adapting to new media. Novelist Stacey D’Erasmo wanted to know how they do it, so she talked with eight artists, including author Samuel R. Delany and poet and visual artist Cecelia Vicuña, to learn the secrets to their longevity. —Claire Kirch

Devil's Contract by Ed Simon [NF]

Millions contributor Ed Simon probes the history of the Faustian bargain, from ancient times to modern day. Devil's Contract is, like all of Simon's writing, refreshingly rigorous, intellectually ambitious, and suffused with boundless curiosity. —SMS

Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel by Yoko Tawada, tr. Susan Bernofsky [F]

Tawada returns with this surrealist ode to the poet Paul Celan and human connection. Set in a hazy, post-lockdown Berlin, Tawada's trademark dream-like prose follows the story of Patrik, an agoraphobe rediscovering his zeal for life through an unlikely friendship built on a shared love of art. —DF

The Anthropologists by Ayşegül Savaş [F]

Savaş’s third novel is looking like her best yet. It's a lean, lithe, lyrical tale of two graduate students in love look for a home away from home, or “trying to make a life together when you have nothing that grounds you,” as the author herself puts it. —JHM

The Coin by Yasmin Zaher [F]

Zaher's debut novel, about a young Palestinian woman unraveling in New York City, is an essential, thrilling addition to the Women on the Verge subgenre. Don't just take it from me: the blurbs for this one are some of the most rhapsodic I've ever seen, and the book's ardent fans include Katie Kitamura, Hilary Leichter, and, yes, Slavoj Žižek, who calls it "a masterpiece." —SMS

Black Intellectuals and Black Society by Martin L. Kilson [NF]

In this posthumous essay collection, the late political scientist Martin L. Kilson reflects on the last century's foremost Black intellectuals, from W.E.B Dubois to Ishmael Reed. Henry Louis Gates Jr. writes that Kilson "brilliantly explores the pivotal yet often obscured legacy of giants of the twentieth-century African American intelligentsia." —SMS

Toward Eternity by Anton Hur [F]

Hur, best known as the translator of such Korean authors as Bora Chung and Kyung-Sook Shin (not to mention BTS), makes his fiction debut with a speculative novel about the intersections of art, medicine, and technology. The Liberators author E.J. Koh writes that Hur delivers "a sprawling, crystalline, and deftly crafted vision of a yet unimaginable future." —SMS

Loving Sylvia Plath by Emily Van Duyne [NF]

I've always felt some connection to Sylvia Plath, and am excited to get my hands on Van Duyne’s debut, a reconstruction of the poet’s final years and legacy, which the author describes as "a reckoning with the broken past and the messy present" that takes into account both Plath’s "white privilege and [the] misogynistic violence" to which she was subjected. —CK

Bright Objects by Ruby Todd [F]

Nearing the arrival of a newly discovered comet, Sylvia Knight, still reeling from her husband's unsolved murder, finds herself drawn to the dark and mysterious corners of her seemingly quiet town. But as the comet draws closer, Sylvia becomes torn between reality and mysticism. This one is for astrology and true crime girlies. —DF

The Lucky Ones by Zara Chowdhary [NF]

The debut memoir by Chowdhary, a survivor of one of the worst massacres in Indian history, weaves together histories both personal and political to paint a harrowing portrait of anti-Muslim violence in her home country of India. Alexander Chee calls this "a warning, thrown to the world," and Nicole Chung describes it as "an astonishing feat of storytelling." —SMS

Banal Nightmare by Halle Butler [F]

Butler grapples with approaching middle age in the modern era in her latest, which follows thirty-something Moddie Yance as she ditches city life and ends her longterm relationship to move back to her Midwestern hometown. Banal Nightmare has "the force of an episode of marijuana psychosis and the extreme detail of a hyperrealistic work of art," per Jia Tolentino. —SMS

A Passionate Mind in Relentless Pursuit by Noliwe Rooks [NF]

In this slim volume on the life and legacy of the trailblazing civil rights leader Mary McLeod Bethune—the first Black woman to head a federal agency, to serve as a college president, and to be honored with a monument in the nation's capital—Rooks meditates on Bethune's place in Black political history, as well as in Rooks's own imagination. —SMS

Modern Fairies by Clare Pollard [F]

An unconventional work of historical fiction to say the least, this tale of the voluble, voracious royal court of Louis XIV of France makes for an often sidesplitting, and always bawdy, read. —JHM

The Quiet Damage by Jesselyn Cook [NF]

Cook, a journalist, reports on deepfake media, antivax opinions, and sex-trafficking conspiracies that undermine legitimate criminal investigations. Having previously written on children trying to deradicalize their QAnon-believing parents and social media influencers who blend banal content with frightening Q views, here Cook focuses on five families whose members went down QAnon rabbit holes, tragically eroding relationships and verifiable truths. —Nathalie Op de Beeck

In the Shadow of the Fall by Tobi Ogundiran [F]

Inspired by West African folkore, Ogundiran (author of the superb short speculative fiction collection Jackal, Jackal) centers this fantasy novella, the first of duology, on a sort-of anti-chosen one: a young acolyte aspiring to priesthood, but unable to get the orishas to speak. So she endeavors to trap one of the spirits, but in the process gets embroiled in a cosmic war—just the kind of grand, anything-can-happen premise that makes Ogundiran’s stories so powerful. —Alan Scherstuhl

The Bluestockings by Susannah Gibson [NF]

This group biography of the Bluestockings, a group of protofeminist women intellectuals who established salons in 18th-century England, reminded me of Regan Penaluna's wonderful How to Think Like a Woman in all the best ways—scholarly but accessible, vividly rendered, and a font of inspiration for the modern woman thinker. —SMS

Liars by Sarah Manguso [F]

Manguso's latest is a standout addition to the ever-expanding canon of novels about the plight of the woman artist, and the artist-mother in particular, for whom creative life and domestic life are perpetually at odds. It's also a more scathing indictment of marriage than any of the recent divorce memoirs to hit shelves. Any fan of Manguso will love this novel—her best yet—and anyone who is not already a fan will be by the time they're done. —SMS

On Strike Against God by Joanna Russ [F]

Flashbacks to grad school gender studies coursework, and the thrilling sensation that another world is yet possible, will wash over a certain kind of reader upon learning that Feminist Press will republish Russ’s 1980 novel. Edited and with an introduction by Cornell University Ph.D. candidate Alec Pollak, this critical edition includes reminiscences on Russ by her longtime friend Samuel R. Delany, letters between Russ and poet Marilyn Hacker, and alternative endings to its lesbian coming-out story. —NodB

Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow by Damilare Kuku [F]

The debut novel by Kuku, the author of the story collection Nearly All the Men in Lagos Are Mad, centers on a Nigerian family plunged into chaos when young Temi, a recent college grad, decides to get a Brazillian butt lift. Wahala author Nikki May writes that Kuku captures "how complicated it is to be a Nigerian woman." —SMS

The Missing Thread by Daisy Dunn [NF]

A book about the girls, by the girls, for the girls. Dunn, a classicist, reconfigures antiquity to emphasize the influence and agency of women. From the apocryphal stories of Cleopatra and Agrippina to the lesser-known tales of Atossa and Olympias, Dunn retraces the steps of these ancient heroines and recovers countless important but oft-forgotten female figures from the margins of history. —DF

August

Villa E by Jane Alison [F]

Alison's taut novel of gender and power is inspired by the real-life collision of Irish designer Eileen Gray and Swiss architect Le Corbusier—and the sordid act of vandalism by the latter that forever defined the legacy of the former. —SMS

The Princess of 72nd Street by Elaine Kraf [F]

Kraf's 1979 feminist cult classic, reissued as part of Modern Library's excellent Torchbearer series with an introduction by Melissa Broder, follows a young woman artist in New York City who experiences wondrous episodes of dissociation. Ripe author Sarah Rose Etter calls Kraf "one of literature's hidden gems." —SMS

All That Glitters by Orlando Whitfield [NF]

Whitfield traces the rise and fall of Inigo Philbrick, the charasmatic but troubled art dealer—and Whitfield's one-time friend—who was recently convicted of committing more than $86 million in fraud. The great Patrick Radden Keefe describes this as "an art world Great Gatsby." —SMS

The Bookshop by Evan Friss [NF]

Oh, so you support your local bookshop? Recount the entire history of bookselling. Friss's rigorously researched ode to bookstores underscores their role as guardians, gatekeepers, and proprietors of history, politics, and culture throughout American history. A must-read for any bibliophile, and an especially timely one in light of the growing number of attempts at literary censorship across the country. —DF

Mystery Lights by Lena Valencia [F]

Valencia's debut short story collection is giving supernatural Southwestern Americana. Subjects as distinct as social media influencers, ghost hunters, and slasher writers populate these stories which, per Kelly Link, contain a "deep well of human complexity, perversity, sincerity, and hope." —DF

Mourning a Breast by Xi Xi, tr. Jennifer Feeley

This 1989 semi-autobiographical novel is an account of the late Hong Kong author and poet Xi's mastectomy and subsequent recovery, heralded as one of the first Chinese-language books to write frankly about illness, and breast cancer in particular.—SMS

Village Voices by Odile Hellier [NF]

Hellier celebrates the history and legacy of the legendary Village Voice Bookshop in Paris, which he founded in 1982. A hub of anglophone literary culture for 30 years, Village Voice hosted everyone from Raymond Carver to Toni Morrison and is fondly remembered in these pages, which mine decades of archives. —SMS

Dinosaurs at the Dinner Party by Edward Dolnick [NF]

Within the past couple of years, three tweens found the fossilized remains of a juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex in North Dakota and an 11-year-old beachcomber came upon an ichthyosaur jaw in southwestern England, sparking scientific excitement. Dolnick’s book revisits similar discoveries from Darwin’s own century, when astonished amateurs couldn’t yet draw upon centuries of paleontology and drew their own conclusions about the fossils and footprints they unearthed. —NodB

All the Rage by Virginia Nicholson [NF]

Social historian Nicholson chronicles the history of beauty standards for women from 1860 to 1960, revealing the fickleness of fashion, the evergreen pressure put on women's self-presentation, and the toll the latter takes on women's bodies. —SMS

A Termination by Honor Moore [NF]

In her latest memoir, Moore—best known for 2008's The Bishop's Daughter—reflects on the abortion she had in 1969 at the age of 23 and its aftermath. The Vivian Gornick calls this one "a masterly account of what it meant, in the 1960s, to be a woman of spirit and intelligence plunged into the particular hell that is unwanted pregnancy." —SMS

Nat Turner, Black Prophet by Anthony E. Kaye with Gregory P. Downs [NF]

Kaye and Downs's remarkable account of Nat Turner's rebellion boldly and persuasively argues for a reinterpretation of the uprising's causes, legacy, and divine influence, framing Turner not just as a preacher but a prophet. A paradigm-shifting work of narrative history. —SMS

An Honest Woman by Charlotte Shane [NF]

As a long-time reader, fan, and newsletter subscriber of Shane's, I nearly dropped to my knees at the altar of Simon & Schuster when her latest book was announced. This slim memoir intertwines her experience as a sex worker with reflections on various formative relationships in her life (with her sexuality, her father, and her long-time client, Roger), as well as reflections on the very nature of sex, gender, and labor. —DF

Mina's Matchbox by Yoko Ogawa, tr. Stephen B. Snyder [F]

Mina's Matchbox is an incredible novel that affirms Ogawa's position as the great writer of fantastical literature today. This novel is much brighter in tone and detail than much of her other, often brutal and gloomy, work, but somehow the tension and terror of living is always at the periphery. Ogawa has produced a world near and tender, but tough and bittersweet, like recognizing a lost loved one in the story told by someone new. —Zachary Issenberg

Jimi Hendrix Live in Lviv by Andrey Kurkov, tr. Reuben Woolley [F]

The Grey Bees author's latest, longlisted for last year's International Booker Prize, is an ode to Lviv, western Ukraine's cultural capital, now transformed by war. A snapshot of the city as it was in the early aughts, the novel chronicles the antics of a cast of eccentrics across the city, with a dash of magical realism thrown in for good measure. —SMS

The Hypocrite by Jo Hamya [F]

I loved Hamya's 2021 debut novel Three Rooms, and her latest, a sharp critique of art and gender that centers on a young woman who pens a satirical play about her sort-of-canceled novelist father, promises to be just as satisfying. —SMS

A Complicated Passion by Carrie Rickey [NF]

This definitive biography of trailblazing French New Wave filmmaker Agnès Varda tells the engrossing story of a brilliant artist and fierce feminist who made movies and found success on her own terms. Film critic and essayist Phillip Lopate writes, "One could not ask for a smarter or more engaging take on the subject." —SMS

The Italy Letters by Vi Khi Nao [F]

This epistolary novel by Nao, an emerging queer Vietnamese American writer who Garielle Lutz once called "an unstoppable genius," sounds like an incredible read: an unnamed narrator in Las Vegas writes sensual stream-of-consciousness letters to their lover in Italy. Perfect leisure reading on a sultry summer’s afternoon while sipping a glass of prosecco. —CK

Survival Is a Promise by Alexis Pauline Gumbs [NF]

Gumbs's poetic, genre-bending biography of Audre Lorde offers a fresh, profound look at Lorde's life, work, and importance undergirded by an ecological, spiritual, and distinctly Black feminist sensibility. Eloquent Rage author Brittany Cooper calls Gumbs "a kindred keeper of [Lorde’s] lesbian-warrior-poet legacy." —SMS

Planes Flying Over a Monster by Daniel Saldaña París, tr. Christina MacSweeney and Philip K. Zimmerman [NF]

Over 10 essays, the Mexican writer Daniel Saldaña Paris explores the cities he has lived in over the course of his life, using each as a springboard to ponder questions of authenticity, art, and narrative. Chloé Cooper Jones calls Saldaña Paris "simply one of our best living writers" and this collection "destined for canonical status." —SMS

The Unicorn Woman by Gayl Jones [F]

The latest novel from Jones, the Pulitzer finalist and mentee of Toni Morrison who first stunned the literary world with her 1975 novel Corregida, follows a Black soldier who returns home to the Jim Crow South after fighting in World War II. Imani Perry has called Jones "one of the most versatile and transformative writers of the 20th century." —SMS

Becoming Little Shell by Chris La Tray [NF]

When La Tray was growing up in western Montana, his family didn’t acknowledge his Indigenous heritage. He became curious about his Métis roots when he met Indigenous relatives at his grandfather’s funeral, and he searched in earnest after his father’s death two decades later. Now Montana’s poet laureate, La Tray has written a memoir about becoming an enrolled member of the Chippewa Little Shell Tribe, known as “landless Indians” because of their history of forced relocation. —NodB

Wife to Mr. Milton by Robert Graves (reissue) [F]

Grave's 1943 novel, reissued by the great Seven Stories Press, is based on the true story of the poet John Milton's tumultuous marriage to the much younger Mary Powell, which played out amid the backdrop of the English Civil War. E.M. Forster once called this one "a thumping good read." —SMS

Euphoria Days by Pilar Fraile, tr. Lizzie Davis [F]

Fraile's first novel to be translated into English follows the lives of five workers approaching middle age and searching for meaning—turning to algorithms, internet porn, drugs, and gurus along the way—in a slightly off-kilter Madrid of the near future. —SMS

September

Colored Television by Danzy Senna [F]

Senna's latest novel follows Jane, a writer living in L.A. and weighing the competing allures of ambition versus stability and making art versus selling out. The perfect read for fans of Lexi Freiman's Book of Ayn, Colored Television is, per Miranda July, "addictive, hilarious, and relatable" and "a very modern reckoning with the ambiguities triangulated by race, class, creativity and love."—SMS

We're Alone by Edwidge Danticat [NF]

I’ve long been a big fan of Danticat, and I'm looking forward to reading this essay collection, which ranges from personal narratives to reflections on the state of the world to tributes to her various mentors and literary influences, including James Baldwin and Toni Morrison. That the great Graywolf Press published this book is an added bonus. —CK

In Our Likeness by Bryan VanDyke [F]

Millions contributor Bryan VanDyke's eerily timely debut novel, set at a tech startup where an algorithm built to detect lies on the internet is in the works, probes both the wonders and horrors of AI. This is a Frankenstein-esque tale befitting the information (or, perhaps, post-information) age and wrought in VanDyke's typically sparkling prose. —SMS

Liontaming in America by Elizabeth Willis [NF]

Willis, a poet and professor at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, plumbed personal and national history for last year’s Spectral Evidence: The Witch Book, and does so again with this allusive hybrid work. This ambitious project promises a mind-bending engagement with polyamory and family, Mormonism and utopianism, prey exercising power over predators, and the shape-shifting American dream. —NodB

Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner [F]

I adore Kushner’s wildly offbeat tales, and I also enjoy books and movies in which people really are not who they claim to be and deception is coming from all sides. This novel about an American woman who infiltrates a rural commune of French radicals and everyone has their private agenda sounds like the perfect page-turner. —CK

Under the Eye of the Big Bird by Hiromi Kawakami, tr. Asa Yoneda [F]

Kawakami, of Strange Weather in Tokyo and People in My Neighborhood fame, returns with a work of speculative fiction comprising 14 interconnected stories spanning eons. This book imagines an Earth where humans teeter on the brink of extinction—and counts the great Banana Yoshimoto as a fan. —SMS

Homeland by Richard Beck [NF]

Beck, an editor at n+1, examines the legacy of the war on terror, which spanned two decades following 9/11, and its irrevocable impact on every facet of American life, from consumer habits to the very notion of citizenship. —SMS

Herscht 07769 by László Krasznahorkai, tr. Ottilie Muzlet [F]

Every novel by Krasznahorkai is immediately recognizable, while also becoming a modulation on that style only he could pull off. Herscht 07769 may be set in the contemporary world—a sort-of fable about the fascism fermenting in East Germany—but the velocity of the prose keeps it ruthilarious and dreamlike. That's what makes Krasznahorkai a master: the world has never sounded so unreal by an author, but all the anxieities of his characters, his readers, suddenly gain clarity, as if he simply turned on the light. —ZI

Madwoman by Chelsea Bieker [F]

Catapult published Bieker’s 2020 debut, Godshot, about a teenager fleeing a religious cult in drought-stricken California, and her 2023 Heartbroke, a collection of stories that explored gender, threat, and mother-and-child relationships. Now, Bieker moves over to Little, Brown with this contemporary thriller, a novel in which an Oregon mom gets a letter from a women’s prison that reignites violent memories of a past she thought she’d left behind. —NodB

The World She Edited by Amy Reading [NF]

Some people like to curl up with a cozy mystery, while for others, the ultimate cozy involves midcentury literary Manhattan. Amy Reading—whose bona fides include service on the executive board of cooperative indie bookstore Buffalo Street Books in Ithaca, N.Y.—profiles New Yorker editor Katharine S. White, who came on board at the magazine in 1925 and spent 36 years editing the likes of Elizabeth Bishop, Janet Flanner, and Mary McCarthy. Put the kettle on—or better yet, pour a classic gin martini—in preparation for this one, which underscores the many women authors White championed. —NodB

If Only by Vigdis Hjorth, tr. Charlotte Barslund [F]

Hjorth, the Norwegian novelist behind 2022's Is Mother Dead, painstakingly chronicles a 30-year-old married woman's all-consuming and volatile romance with a married man, which blurs the lines between passion and love. Sheila Heti calls Hjorth "one of my favorite contemporary writers." —SMS

Fierce Desires by Rebecca L. Davis [NF]

Davis's sprawling account of sex and sexuality over the course of American history traverses the various behaviors, beliefs, debates, identities, and subcultures that have shaped the way we understand connection, desire, gender, and power. Comprehensive, rigorous, and unafraid to challenge readers, this history illuminates the present with brutal and startling clarity. —SMS

The Burning Plain by Juan Rulfo, tr. Douglas Weatherford [F]

Rulfo's Pedro Páramo is considered by many to be one of the greatest novels ever written, so it's no surprise that his 1953 story collection The Burning Plain—which depicts life in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution and Cristero Revolt—is widely seen as Mexico's most significant (and, objectively, most translated) work of short fiction. —SMS

My Lesbian Novel and TOAF by Renee Gladman [F/NF]

The perpetually pitch perfect Dorothy, a Publishing Project is putting out two books by Renee Gladman, one of its finest regular authors, on the same day: a nigh uncategorizable novel about an artist and writer with her same name and oeuvre who discusses the process of writing a lesbian romance and a genre-smashing meditation on an abandoned writing project. What's not to love? —JHM

Dear Dickhead by Virginie Despentes, tr. Frank Wynne [F]

I'm a big fan of Despentes's caustic, vigorous voice: King Kong Theory was one of my favorite reads of last year. (I was late, I know!) So I can't wait to dig into her latest novel—purported to be taking France by storm—which nods to #MeToo in its depiction of an unlikely friendship that brings up questions of sex, fame, and gendered power. —SMS

Capital by Karl Marx, tr. Paul Reitter [NF]

In a world that burns more quickly by the day—after centuries of industrial rapacity, and with ever-increasing flares of fascism—a new English translation of Marx, and the first to be based on his final revision of this foundational critique of capitalism, is just what the people ordered. —JHM

Fathers and Fugitives by S.J. Naudé, tr. Michiel Heyns [F]

Naudé, who writes in Afrikaans, has translated his previous books himself—until now. The first to be translated by Heyns, a brilliant writer himself and a friend of Naudé's, this novel follows a queer journalist living in London who travels home to South Africa to care for his dying father, only to learn of a perplexing clause in his will. —SMS

Men of Maize by Miguel Ángel Asturias, tr. Gerald Martin [F]

This Penguin Classics reissue of the Nobel Prize–winning Guatemalan writer's epic novel, just in time for its 75th anniversary, throws into stark relief the continued timeliness of its themes: capitalist exploitation, environmental devastation, and the plight of Indigenous peoples. Héctor Tobar, who wrote the forward, calls this "Asturias’s Mayan masterpiece, his Indigenous Ulysses." —SMS

Good Night, Sleep Tight by Brian Evenson [F]

It is practically impossible to do, after cracking open any collection of stories by the horror master Evenson, what the title of this latest collection asks of its readers. This book is already haunting you even before you've opened it. —JHM

Reservoir Bitches by Dahlia de la Cerda, tr. Julia Sanches and Heather Cleary [F]

De la Cerda's darkly humorous debut story collection follows 13 resilient, rebellious women navigating life in contemporary Mexico. Dogs of Summer author Andrea Abreu writes, "This book has the force of an ocean gully: it sucks you in, drags you through the mud, and then cleanses you." —SMS

Lost: Back to the Island by Emily St. James and Noel Murray [NF]

For years, Emily St. James was one of my favorite TV critics, and I'm so excited to see her go long on that most polarizing of shows (which she wrote brilliantly about for AV Club way back when) in tandem with Noel Murray, another great critic. The Lost resurgence—and much-deserved critical reevaluation—is imminent. —SMS

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin [F]

Who could tire of tales of Parisian affairs and despairs? This one, from critic and Art Monsters author Elkin, tells the story of 40 years, four lives, two couples, one apartment, and that singularly terrible, beautiful thing we call love. —JHM

Bringer of Dust by J.M. Miro [F]

The bold first entry in Miro’s sweeping Victorian-era fantasy was a novel to revel in. Ordinary Monsters combined cowboys, the undead, a Scottish magic school, action better than most blockbuster movies can manage, and refreshingly sharp prose astonishingly well as its batch of cast of desperate kids confused by their strange powers fought to make sense of the world around them—despite being stalked, and possibly manipulated, by sinister forces. That book’s climax upended all expectations, making Bringer of Dust something rare: a second volume in a fantasy where readers have no idea where things are heading. —AS

Frighten the Horses by Oliver Radclyffe [NF]

The latest book from Roxane Gay's eponymous imprint is Radclyffe's memoir of coming out as a trans man in his forties, rethinking his supposedly idyllic life with his husband and four children. Fans of the book include Sabrina Imbler, Sarah Schulman, and Edmund White, who praises Radclyffe as "a major writer." —SMS

Everything to Play For by Marijam Did [NF]

A video game industry insider, Did considers the politics of gaming in this critical overview—and asks how games, after decades of reshaping our private lives and popular culture, can help pave the way for a better world. —SMS

Rejection by Tony Tulathimutte [F]

Tulathimutte's linked story collection plunges into the touchy topics of sex, relationships, identity, and the internet. Vauhini Vara, in describing the book, evokes both Nabokov and Roth, as well as "the worst (by which I mean best) Am I the Asshole post you’ve ever read on Reddit." —SMS

Elizabeth Catlett by Ed. Dalila Scruggs [NF]

This art book, which will accompany a retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum organized by Scruggs, spotlight the work and legacy of the pioneering printmaker, sculptor, and activist Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012), who centered the experiences of Black and Mexican women in all that she did and aspired "to put art to the service of the people." —SMS

The Repeat Room by Jesse Ball [F]

I often credit Jesse Ball's surrealist masterpiece A Cure for Suicide with reviving my love of reading, and his latest got me out of my reading slump once again. Much like ACFS, The Repeat Room is set in a totalitarian dystopia that slowly reveals itself. The story follows Abel, a lowly garbageman chosen to sit on a jury where advanced technology is used to forcibly enter the memories of "the accused." This novel forces tough moral questions on readers, and will make you wonder what it means to be a good person—and, ultimately, if it even matters. —DF

Defectors by Paola Ramos [NF]

Ramos, an Emmy Award–winning journalist, examines how Latino voters—often treated as a monolith—are increasingly gravitating to the far right, and what this shift means America's political future. Rachel Maddow calls Defectors "a deeply reported, surprisingly personal exploration of a phenomenon that is little understood in our politics." —SMS

Monet by Jackie Wullshläger [NF]

Already available in the U.K., this biography reveals a more tempestuous Claude Monet than the serene Water Lilies of his later years suggest. Wullschläger, the chief art critic of the Financial Times, mines the archives for youthful letters and secrets about Monet’s unsung lovers and famous friends of the Belle Époque. —NodB

Brooklynites by Prithi Kanakamedala [NF]

Kanakamedala celebrates the Black Brooklynites who shaped New York City's second-largest borough in the 19th century, leaving a powerful legacy of social justice organizing in their wake. Centering on four Black families, this work of narrative history carefully and passionately traces Brooklyn's activist lineage. —SMS

No Ship Sets Out to Be a Shipwreck by Joan Wickersham [NF]

In this slim nonfiction/poetry hybrid, Wickersham (author of National Book Award finalist The Suicide Index) meditates on a Swedish warship named Vasa, so freighted with cannons and fancy carvings in honor of the king that it sank only minutes after leaving the dock in 1682, taking 30 lives with it. After Wickersham saw the salvaged Vasa on display in Stockholm, she crafted her book around this monument to nation and hubris. —NodB

Health and Safety by Emily Witt [NF]

I loved Witt's sharply observed Future Sex and can't wait for her latest, a memoir about drugs, raves, and New York City nightlife which charts the New Yorker staff writer's immersion into the city's dance music underground on the cusp of the pandemic—and the double life she began to lead as a result. —SMS

[millions_email]

Margaret Wise Brown and the Mystery of Mood

1.

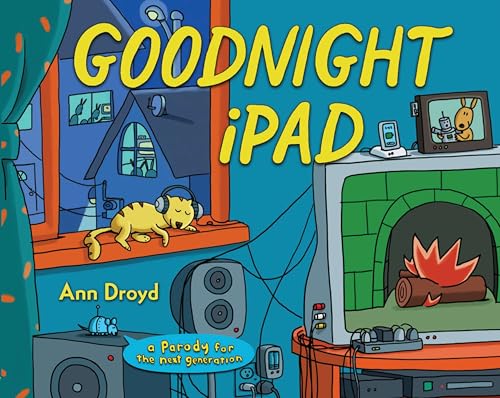

Unlike most people, with or without children of their own, I had not come to Margaret Wise Brown by the popular-to-the-point-of ubiquitous Goodnight Moon. Even if I had never read Goodnight Moon (but hasn’t everyone read Goodnight Moon?), it was impossible not to encounter it in every children’s bookstore and airport across the land where it not only existed in its original form but in endless imitation from Goodnight _____ (fill in the blank of the city or state to Good Night Farm, Zoo, North Pole, Ocean, World, Galaxy, and Baby Jesus, to say nothing of parodic spin-offs like Goodnight Goon, Goodnight iPad, and Goodnight Husband, Goodnight Wife. But Goodnight Moon wouldn’t prove to be the mood lure that would have me wanting to enter more deeply into the worlds created by Margaret Wise Brown.

I found Brown lurking with a start in the pages of a 900–page book on noise by cultural historian Hillel Schwartz. I had invited the scholar and translator to the campus where I teach to discuss his book in a class in “literary acoustics” --a course in which we sought to transform words on pages and so much of what we took about our lives to be self-evident by turning our attention to sound, voice, noise, and silence. Schwartz introduced the students and me to one book in a series of books devoted to listening by Brown, the paradoxically titled The Quiet Noisy Book.

It was interesting at the outset to think about the vast mood influence the magic of one of Brown’s books had cast into the nighttime wells of millions of children over a period of several decades and still to this day. Then, to pause to consider how little any reader, be they parent or child, knew about the particular geometry of her life, to say nothing of the scores of books she wrote that haven’t yet enjoyed the same ascendency as Goodnight Moon including her Noisy Book series, or those she wrote under a handful of pseudonyms. Could it matter to our experience of the book to know that Brown didn’t live to see Goodnight Moon thrive, that she died young, at 42 in 1952, exiting life with the kind of boisterous exuberance she was known for: cause of death was a cancan-type kick of her leg into the air following a minor surgery. She died instantly of an embolism. In an equally strange twist of fate, in her will, Brown had named the child of a friend the right to all monies earned by her books should he survive her, but the boy, who never completed high school and who gained a reputation for destroying public property and beating people up, grew up to squander the millions.

At the center of the famous tale was a bunny, and Brown had grown up with bunnies and other animals. As an adult, she once took a bunny on a train with her en route to a date; but, could a reader imagine it? -- as a child, she had also skinned a bunny. The houses she lived in were like hutches -- in the middle of Manhattan, a cottage that she called Cobble Court; on a ruggedly beautiful island in Maine named Vinalhaven, a former quarryman’s house she dubbed “The Only House.” Brown’s biographer, Leonard Marcus, describes the house as an uncomfortable extravagance: it wasn’t wired for telephone service or electricity and lacked indoor plumbing, but Brown made sure the larder was stocked with “champagne, fresh cream, imported cheeses and other such necessities.” A well served as a fridge, as did the cool, running waters of a nearby brook, from which she might surprise a visitor with a bottle of wine. Rainwater was collected for bathing, and three outhouses were positioned “for the sake of the view”: “a mirror had been nailed to one of the apple trees in the yard, and a pitcher and basin were left out on a battered Victorian washstand. First-time visitors would be surprised on opening the drawers to find the freshly laid supply of scented soaps and toiletries of Margaret’s ‘Boudoir.’” One part of the house brought the outside in through a collection of small mirrors, “each differently framed and made flush with its neighbors.” The mirrors were hung across from a door that opened onto a “sheer fifty foot drop,” and positioned in such a way each to reflect a “different image of the sea” in succession. People finding themselves in the mirrors, would glimpse themselves as “plural.”

I don’t recall which detail from Hillel Schwartz’s work on Brown and noise made me ask him about her romantic life. I only remember a feeling of a life lived differently and athwart, and a desire to draw closer to her, whatever the answer might be. I wasn’t looking to find myself in her, but learning that she’d spent most of her life in a relationship with a woman poet who called herself Michael Strange and who had been the ex-wife of John Barrymore filled me with a perverse delight. Picture this: when Michael was in the mood, she called Margaret “Bun;” when Margaret was in the mood, she called Michael “Rabbit” (those really were their pet names for one another). I loved how the idea of a “childless” lesbian having devised one of the most classic books for children gave the lie to maternity as the only or most natural route to knowing how to be with children. I wondered if hospitals that sent copies of the book home with newborns would discontinue the practice if they knew the book’s author had been queer. Would all those folks who lulled their children to sleep with Goodnight Moon rest easy if they knew the little prayer was birthed by a lesbian consciousness? Might they worry that Goodnight Moon could unconsciously shape a mood realm deep inside the child that might make him grow up gay?

Come to think of it, all of the mood-room makers to have drawn my interest are by coincidence queer insofar as all three -- Florence Thomas, Thomas Hubbard, Margaret Wise Brown -- lived out of tune with the hum of a neatly domesticating hetero norm. Florence Thomas, I recently learned, and as I’d imagined, enjoyed her days in retirement alone with her cat, her garden, and a basement studio where she carved abstract art out of wood. “‘I’m a cat person,’ Florence Thomas told a local reporter in 1971, ‘So I am really fondest of ‘Puss and Boots.’” “You have to know how to be a scavenger,” she said, referring to the suite of materials used in her scenes. “It’s much easier now since we have plastic flowers and leaves. I used to bring live things from the garden.” Though retirement would give her time “to renew old friendships” -- she was planning a major trip to Australia and New Zealand with one friend -- she explained she wanted to work on her garden first. This wasn’t a garden-variety garden providing flowers for the table or tomatoes for a stew. Spanning one half-acre, it was a form of applied dedication by a specialist-eccentric: Thomas had cultivated one hundred varieties of rhododendrons. She continued to make 3-D constructions, but now by way of what was known as the Personal View-Master camera: a device that people could use to make View-Master reels with images they themselves took, based, that is to say, on their own lives.

Hubbard wasn’t exactly a solitary soul, but he lived at an apparent distance from his wife, who has been described as emotionally unwell, devoting himself to his students, his art, and his summer travel in turn.

Brown had experienced attachments to other women and a near marriage to a man before she met Michael Strange. Unfortunately, her relationship with Strange wasn’t, in the long term, a happy one. Strange comes off as abusive in the end, with Brown the ever-pining and unfulfilled lover. One of numerous painfully poignant junctures in Leonard Marcus’s account of their relationship has Brown hiring a lobsterman to build a special house just for Michael Strange near to Brown’s “Only House” on Vinalhaven. Since Strange rarely joined her there, perhaps Brown thought designing a “Picture Window” using an ornate picture frame she’d found in a Rockland antique shop trained on a spruce forest would do the trick. But she was wrong. Nevertheless, an unconventionally attuned Brown was involved in experiments in living and in writing all her short life -- having been the literal voice to prompt Gertrude Stein to compose a children’s book, with the result being Stein’s 1939 The World is Round illustrated by the same artist who pictured Goodnight Moon, Clement Hurd. Brown’s Noisy Book series, which came into print around the same time, grew directly out of her work with Lucy Sprague Mitchell, founder of the Bank Street School whose experiments in early childhood education in the early 20th century included encouraging children to be noisy rather than disciplining them into silence. Many of Brown’s books in progress were tried out, so to speak, on children at the school.

The Noisy books, Brown explained, “‘came right from the children themselves -- from listening to them, watching them, and letting them into the story when they are much too young to sit without a word for the length of time it takes to read a full-length story to them. I mean three- and two-year olds.” At the center of the series is a little black dog named Muffin who stands in place of a child -- one imagines the child-reader identifying with him -- but who, on account of his being a dog, has a keener sense of hearing than a child. Or does he? The books are meant to meet children in that time before they’ve come to use language fully to mediate desire and their world, that period when looking hasn’t yet replaced listening as the form of reading, where letters aren’t yet yoked to sounds but float, one form among others on a page splashed with Leonard Weisgard’s bright colors and Brown’s colocation not just of words bound to meanings but of phonemes’ clattering in imitation of sound.

If Gertrude Stein famously discovered the difference between sentences and paragraphs by listening to the rhythm with which her dog lapped the water in his bowl, Margaret Wise Brown understood the equation in reverse when she included dogs among her listener-readers. A dog can train a writer to make prose; and, a writer can write a book that a dog can understand. “Dogs,” Brown wrote, “will also be interested in ‘the Noisy Books’ the first time they hear them read with any convincing suddenness and variety of whistles, squeaks, hisses, thuds, and sudden silences following an unexpected BANG.”

Here I am, a dogless adult, tethered to and transfixed by Brown’s protagonist dog. The play-space she creates for him and invites us to enter in her books isn’t exactly a-brim with frolic and jaunt, a run in the park, a pat or a pant, the tossing of a ball before being tucked in with a biscuit and warm milk for the night. These aren’t easy or straightforwardly narrated books. They are tantalizingly difficult; most have the riddle of sound at their center; all are marked by absence, for isn’t it the nature of sound to emanate from the object world but remain detached from it; to seem to reside within an object but not be traceable to it; to exist as a solid experience of sense but to remain ungraspable, sometimes unlocatable, at heart, ephemeral?

Meaningful and meaningless sounds were the bases of our moods -- possibly the earliest molds for the form a mood could take -- and sound is mood’s analog.

In The Quiet Noisy Book, Muffin is awakened by a “very quiet noise.” “What could it be?” the narrator asks, then provides a set of answers in the form of questions whose examples are beyond audition, or imaginary: “Was it butter melting?” “Was it an elephant tip-toeing down a stairs?” “Was it a skyscraper scraping the sky?” Teasing the limit of our senses to meet the reach of our imagination, gathering into a book-as-net all that coexists simultaneously with us and beyond us, offering a promise of presence -- the blank filled in -- if only we could be willing to listen hard enough, the book answers each possibility with the word “no,” without at the same time canceling its belief in the possibility that what Muffin could be hearing was “a fish breathing,” say.

What do we wake to? What is the sound that’s waking Muffin up? It’s something very quiet, but there. It’s “quiet as a chair. Quiet as air.” It’s something Muffin knows, but do you know what it is, dear reader? By now you could be terrified or mesmerized or both, when, splash, it is the sun coming up. The sound of the sun coming up is accompanied by conventional harbingers of joy -- roosters crowing and such -- but Brown also leaves the child -- and the adult reader -- with puffs of cloud heavy with mystery, my favorites being, it was the sound “of a balloon about to pop,” and “it was a man about to think.”

Here Brown had gifted me the finest definition of a mood, and one defying explanation. Mood: it was the sound of a person about to think. What qualities inhere in the sound of a person about to think? Does thought really admit of pause? What form of silence have we here, for doesn’t the “about to,” though yoked to sound, imply an absence of sound? A soundless sound?

Philosophers of silence spoke of silence as its own active presence, not merely a negation of sound. Of brusque or smooth silences, of silences yoked to utterance, and requisite to language’s meaningmaking capacity, and silence as its own live phenomenon, with its own temporality, independent of sound. Of silence as predictive of the type of utterance to follow, of rhythmic silence, silence as the place of anticipatory alertness, and silence that serves as an end point or terminus, a concluding silence. Silence that casts a spell, and silence that lifts a spell. Certainly, there is no such thing as silence pure and simple, and if any of us were asked to generate types of silence, we could come up with enough examples in an instant to fill a page -- just now, radio silence; the silence enjoyed between intimates; awkward silence; and how about the silence that pervades the experience of reading? Does that bear any resemblance to the sound of a person about to think?

Margaret Wise Brown is the person whose picture books ask these questions, not I, and when she translates the “new day” in The Quiet Noisy Book into the dawn of life’s unanswerables, she opens her reader to possibilities of heaviness or light, of greeting the unknown with a mood of curiosity or hiding under the covers depressed by the prospect of pondering.

If we equate the sound of a person about to think with a form of soundlessness, that’s only because, as adult readers, we think of thought as word-bound, a kind of talking to oneself, and sound, therefore, as one sign in a system of language, like the space between words, say. But what if the sound of a person about to think were a tone or air, a vibration or an atmosphere that thought depended on, no matter the form thought took; what if it was understood to be a presence rather than an absence, albeit one we might not be able to translate into words?

What I notice about the books in Margaret Wise Brown’s Noisy series is how, in each of them, she confides in absence, allows for it, enfolds a reader in it even: she makes absent presences a field of play. For, whether it is The Indoor Noisy Book, The Noisy Book, The Winter Noisy Book, The Seashore Noisy Book, The Summer Noisy Book, or The Country Noisy Book, to name a few, there is always something menacing, askew, uncanny, inexplicable, in excess, or ghosted to contend with or consort with. It’s that same quality that provides a mood for or to childhood but that is forgotten or covered over in adulthood, in which case, adult moods are a form of the comforting blanket that one had lain beneath when such stories had been read to one; they are the cover for a more mystifying cloudscape forgotten but ever-hovering.

There is a kind of ultimate silence, of course, that, if we try to “think” it, fills the mind with existential dread -- the blotting of consciousness, the death-in-store that would jettison us into, well, I can’t think of a better figure for it than “outer space.” Celestial music or the music of the spheres must just be something humans have devised to console themselves with when confronted with the inconceivable absoluteness of the silence that is death. Mood is that silence momentarily animated.

2.

In several of the Noisy books, Muffin’s eyesight or some other aspect of his sensorium is compromised so that he has to rely more fully on his capacity to listen. In The Noisy Book, he’s gotten a cinder in his eye and is required to wear a blindfold. In The Indoor Noisy Book, he has caught a cold and is forced to stay inside making him more acutely aware of the noises in the house. In The Seashore Noisy Book, he is disoriented by the fact of his hearing, for the first time, the sounds of the ocean. As the book nears its end, he hears a splashing sound, and, as always, we are invited along with Muffin to try to attach the sound to its source: “Was it the sun falling out of the sky?” “Was it a sea horse galloping?” Earlier, we’re asked to listen for the light of moon and stars on water. The “answer” to the splashing is that Muffin has fallen out of the boat and it is his own flailing that he’s caught in the sound of. He began by falling into a mood -- the mood of the sea -- and ends by being rescued from his nearly drowning there. This particular meta-ending is just one instance of the mystery of sound -- and by affiliation, mood -- being answered by a scenario of oddly proportioned dimensions in which nothing is resolved but where we are asked in effect to squeeze the large round ball attached to a scary clown’s nose.

The end of The Noisy Book might be the most delightfully perverse in this respect. Here, blindfolded Muffin hears a squeaking whose source he can’t identify. Neither a garbage can nor the house nor a mouse nor a policeman, the answer is “a baby doll / And they gave the baby doll to Muffin for his very own.” The problem, or pleasure, for a reader, though, is that the anthropomorphizing has Muffin playing with a facsimile of a human rather than with a doll in the form of a diminutive dog -- a puppy doll, and that the illustration shows the doll to be nearly twice Muffin’s size. He can barely hold the doll, but he’s propped himself, sans blindfold now, as if posing for a snapshot. Muffin and the reader in their collaborative investigations of sound and mood seem to have won the booby prize.

The Winter Noisy Book might broach the most uncanny territory of all once we realize it’s Brown’s version of Muffin Had Two Daddies. Winter has come; night is cold, and still, beyond the windows; stark, black branches rattle against the windowpane. Muffin hears a thud thud thud scrunch scrunch scrunch -- what was that? Rather than provide her usual series of playful speculations, Brown works together with her illustrator -- this time an abstract painter other than Weisgard, Charles G. Shaw -- to produce a frighteningly stark page. The illustration shows an empty dog collar and leash, and a shade drawn against the darkness in a furniture-less room. One sentence is spelled across the white floor of the room. As answer to the question of the scrunching, it could describe the entry of a sci-fi menace: “The fathers were coming home.” Does the empty collar mean the dog has fled or that the dog has died? More benignly, could it mean the fathers are the ones who will take Muffin out for a walk? The ominous mood is dispelled -- the blank of the page filled in -- by the introduction of a perfectly normal-seeming domestic scene comprising two men. They produce sounds that Muffin listens to, like laughter and the dropping of a nickel, the turning on of a light, and the b-r-r-r-r of a shiver before they stretch their legs in front of the roaring fireplace where they sip cocktails and crunch on celery. Muffin is merrily spread on the rug before his bachelor fathers -- one clad in neatly striped pants, the other, solid blue.

Leonard Weisgard, who had been a dancer and a Macy’s window display designer before he turned to children’s book illustration, mastered the magic of minimalism in the Noisy books. The palette is simple, relying sometimes on no more than four colors in the course of a book, including the noncolors, black and white, especially in combination with primaries. A page could turn entirely yellow, daylight reduced to a trapezoid of blue against red. He arrives at images -- the shape of icicles, for example -- by subtracting rather than filling in, or by cutting out and pasting in. If I find myself wanting to roam around inside an illustration, is that the same as reading?

The endpapers of The Indoor Noisy Book hold my attention the way the interior of a doll’s house once had. For a two-page spread, he’s cut one side of the walls out of Muffin’s four-story house so we can climb the small ladder in the basement through a hatch to arrive in the dining room whose table sits below a Victorian tub in the bathroom on the floor above it, which sits beneath the most interesting room of all: the attic. There’s a bed frame and an equally empty, though ornate, picture frame. There’s a dress frame with exaggerated curves. A bandbox and a dome-lidded trunk. A taxidermied moose head. There’s a piano.

Is the power of the drawing -- see how it draws me even now, drawing my adult eye, compelling me to redraw it by way of words -- fueled by nothing more than reminiscence -- just one more instance of a version of 3-D paper cutout houses enjoyed in childhood? When a mood space is activated by a work like this, we are put in contact with something ever present but impalpable. It’s never so simple a thing as a reminder of or a return to something from our past; it’s more a how than a what.

There was a sentence like a conundrum that appeared in Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht’s work on mood that I also wished to understand and most definitely felt I was experiencing. Describing what happens when literature creates a mood, Gumbrecht made a distinction thus: “For what affects us in the act of reading involves the present of the past in substance -- not the sign of the past or its representation.” I’m not compelled by Weisgard’s illustrations because they bring my past back to me by pointing to it in replica but because something has been made possible in the readerly transaction of color, line, and consciousness that puts me literally in contact with a piece of a reconstituted atmosphere as if to say I once was in that dream but forgot I’d never left its precincts. Now I not only recognize its outline but also feel what it is to be buoyed inside its envelope. It’s not a forgotten place but a place where I always am -- part of my mood repertoire -- but which I fail to see.

While Weisgard’s elaborated interior might seem like just one more iteration of a repetition of examples -- enter a return to an already-scripted View-Master -- there were other aspects of his illustrations for Brown’s books that turned a key to unlock a mood and that were much less legible. They were not at all “representational.” These were absorptive planes (pure blots of color, where the feeling of the paper as recipient of a hue was as important as the fact of color itself), and stencils.

Numerous of the images in The Indoor Noisy Book are finely dotted or shaded as though they were applied through screens or with sponges onto the white page below rather than fully filled in, and bunches of tiny flecks of color mist around their edges like the scatter left by a spray-painted stencil. Maybe a child is meant to read such touches as a sign of its maker having fun: “These pictures are ones you too could make,” the speckled fringes say, “some afternoon of arts and crafts.”

For this adult reader, it matters that I touch the page when turning it, and when I do, I’m suffused with a smell of sour milk and hay. White-colored goo had been applied to a piece of bright red particleboard, four by four inches square. Had we been given sprayers or had the adults sprayed our hands? You pressed into the board, painted the white goo on, and what remained as an absence but also as an imprint was your child hand. Overly warm milk in a small waxen carton probably was meted out to us after nap time in kindergarten like dribbles of white into the mouths of mewing kittens. But the “stuff” we used to “make our hands” that day was milky, too, and sour smelling. The hand left on a block of red detached from a body was meant as a gift to our mothers, but it wasn’t something I wanted to give to mine. The hand lay in a drawer as a shadow self. It was the hand from a body that could only be described as “bleating.” If this wasn’t the stuff of an originary mood, I don’t know what else could be. And it was immanent in the quiet noisy books of Margaret Wise Brown.

Stencils could be a form for mood itself: there was always something missing from them; a stencil was a means, and its end. Would the stenciling in The Indoor Noisy Book create a mood no matter the particular reader’s relationship to stencils, then? Or in order for it to do its work, need it be tied to a remembrance of stencils past? To me, it seemed struck from the same granules as a mood that I harbored, one part quavering voice, one part shadow.

3.

Stencils can be found in caves dating to 10,000 B.C. And guess what they depict? Hands. Entire walls with nothing but hands like paw prints as records of human yearning. Early man, delighted with a technique of missing and finding himself at the same time. Hands as outlines feeling for something in the rock. Not pushing it upward like Sisyphus but transmitting or receiving warmth from it. Then there were those uses of hands that magically—with no more than a set of stick legs here, a wattle there—transformed the outline of palm and fingers on a page into a turkey. I wonder if we effected such magical transformations in the same week that we spray-painted our hands or in the week following. No doubt we were also instructed to give our turkey-hands to our mothers.

In even earlier childhood, when naming is the game but not yet reading, you might be placed before the sort of “puzzle” made of wooden figures that you are meant to fit into shapes cut out for them. The shapes -- either abstract or figural -- have knobs attached to them that make them seem like lids or doors. No doubt the point of such puzzles is to aid a child in the development of hand-eye coordination while at the same time teaching her words. Assuming that is a skill I’ve mastered, what kind of pleasure could such a puzzle hold out for me now?

I bought one such puzzle at a flea market because I had a hunch it belonged with the View-Masters and picture books in a cupboard marked “the mystery of mood.” I also found it aesthetically pleasing: in its world, a duck could reside in the same row as a clock, a house was the size of a crow, and a cat that of a sailboat. Each thing was unstuck from any context and returned to its thingness: one purely red chair; a single boot without the need for a foot or mate. I felt it had something to teach me, but I also quite simply enjoyed it: placing the wooden tree snug in the slot suited only for it and it alone, doing the same with the dog, the hen, and the jug must work to quell the chaos in any adult life.

The principle behind the puzzle was as riddled with absent presences as any book by Margaret Wise Brown and just as rife with a mood of earliest reading. Fitting each figure into its slot, you earn the prize of getting something right, case closed. But you also cover something over; each time you remove a form, something is revealed: hiding inside each home for a form is its word. It’s easy to get the words wrong -- one reason no doubt that the manufacturer called the puzzle Simplex, brother of complex: instead of “boat,” the slot yields “yacht.” Where I recognize a creamer, it tells me it’s a “jug.” Instead of a crow, it offers the word “bird.” An obvious Christmas tree is simply a tree. The figure meant for a slot whose inner wall reads “teddy” is missing from this puzzle. I think if I saw it, I’d call it a bear.

Learning to call things by their right names; imagining words as entities, or answers, that hide inside things; trading in the feel, and the shape, of the thing for its word so that you can eventually advance from puzzles to reading: our moods lurk in the interstices, for our mood is the story no one asked us to devise when presented with the shape of the thing. It’s the missing link between the word and the thing, and it’s also the cloak that shrouds the word in mystery. It’s the shape left inside the toy box cut off from the hand that held it.

It was the sound of a balloon about to pop.

Reprinted with permission from Life Breaks In: A Mood Almanack. Published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2016 Mary Cappello. All rights reserved.