In the last few months, Alaska has been brutal to people I know. A friend who’s so knowledgeable about the wilderness he teaches college classes on the subject got mauled by a bear on a mountain outside Haines. The outdoors-savvy boyfriend of a friend disappeared while running or hiking outside Nome. A bush pilot I flew with last year crashed into Admiralty Island; he and all but one of the passengers died.

But if Alaska can be brutal, it can also be transcendent. Another friend recently caught a beautiful king salmon with a fly she tied herself; the photo of her holding it conveys a form of worship. Earlier this summer, I traveled to Admiralty Island — Kootznoowoo, or “fortress of the bears” in Lingít, the indigenous language of the area. For hours, we watched male and female brown bears court — running away, snarling, following each other as if they were connected by an ever-shortening rope. For the last few years, my boyfriend and I have packed inflatable boats, food, and our tent and floated down a different river in Alaska or the Yukon — the Pelly, the Big Salmon, the Nisutlin, the Stikine. We’ve listened to a dozen wolves howl and bark on each side of the river around us long into the night. We’ve watched a pack of them ghost in and out of the trees, barely visible as they run. We’ve seen kingfishers beat in place above the water, ravens chase ospreys, a cow moose sheltering her two calves as she watched us float by, black and brown bears eating sedges.

Many fiction writers get wilderness wrong.

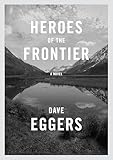

I recently received a copy of Dave Eggers’s newest book, Heroes of the Frontier, which is set in Alaska. I like Eggers’s books. I first read A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius in high school, when my love for it verged on the babbling. I appreciate the generous, expansive nature of his writing, and because he’s Dave Eggers, I really enjoyed everything about the new book that relates to people. Josie, the protagonist, is complicated, believable, moving, frequently hilarious — so is the way she interacts with others. The towns, and their quirky, touristy craziness, ring true.

I recently received a copy of Dave Eggers’s newest book, Heroes of the Frontier, which is set in Alaska. I like Eggers’s books. I first read A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius in high school, when my love for it verged on the babbling. I appreciate the generous, expansive nature of his writing, and because he’s Dave Eggers, I really enjoyed everything about the new book that relates to people. Josie, the protagonist, is complicated, believable, moving, frequently hilarious — so is the way she interacts with others. The towns, and their quirky, touristy craziness, ring true.

This is not the case for the wilderness. At one point in the book, Josie watches a water snake emerge from a river and eat a snail. The only problem? There are no snakes in Alaska. In a later section, Josie and her two children pause to watch “a ten point buck.” Only problem? There are no “ten point bucks” in interior Alaska. Every now and then mule deer stray over from Canada, but when they do they’re so unusual people write newspaper articles about them. A “ten-point buck?” No.

In the first ten pages, Josie and the kids drive through an animal park that advertises its Alaskan mammals. They see “a pair of moose, and their new calf, none of them stirring.” I realize this is a zoo, but male moose do not hang around with their calves. They saw “an antelope, spindly and stupid; it walked a few feet before stopping to look forlornly into the grey mountains beyond. Its eyes said, Take me, Lord. I am now broken.” Again, a zoo, but there are no antelope in Alaska. If it wanted to flee into the Alaskan mountains it would find itself just as lonely and would die of cold, wolves, or starvation come winter. When they’re finished with the zoo, a ranger points “to a mountain range nearby, where, he said, there was a rare thing: a small group of bighorn sheep, cutting a horizontal line across the ridge, east to west.” Bighorn sheep do not live in Alaska. Alaska has Dall sheep, which are a different species.

To most Alaskans, these are big mistakes. But when reading Heroes of the Frontier, I was also thinking about something more intangible — the nature of a place versus the nature of a story set in that place.

Much of the novel is set on the road, but at the end Josie and her two children, Paul and Ana, decide to go for a hike. It ends up taking much longer than they anticipated, and they’re unprepared. There is lightning. It begins to rain; they get soaked. They decide not to go back the way they’ve come, but to run from copse of trees to copse of trees, somehow staying on the trail. If there’s one thing indicated by the very large number of people that get lost and die or have to be rescued in the Alaskan wilderness every year, it’s that it is very easy to accidentally veer off-trail, especially if the trail is not well traveled or near a city, especially if it’s not the best of circumstances. But somehow, despite the fact that they’re literally running for their lives during a massive storm, Josie and the kids keep finding clues as to where they’re going.

There’s something described as “an avalanche,” though its only elements seem to be rock and shale — Josie slides across it on her back with her upper body clad in only a bra, but Eggers never mentions snow, ice or cold. Somehow, Josie and her children make it to a cabin she didn’t realize was there when they began the hike. It is decked out with balloons and a feast for the “Stromberg Family Reunion.” I can get with a cabin; a cabin can be the deus ex machina of real-life salvation. But a cabin decorated and then abandoned, miles and an arduous hike into the wilderness, containing a table “overflowing with juices and sodas, chips, fruit and a glorious chocolate cake under a plastic canopy?” I wanted to believe in this cabin — I hope there is a cabin like that out there for all of us — but I could think of too many people for whom this cabin didn’t exist.

I am by no means immune to the perils of writing wilderness myself. I recently showed a new chapter in my novel-in-revision to my boyfriend Bjorn, a life-long Alaskan. In it, a young girl wanders around lost on Chichagof Island. It was the chapter he liked least.

“She would be afraid,” he said. “When does she start feeling like prey?”

My problem was that I wanted my character to be challenged, but like Eggers, I hadn’t accounted for the reality of the place that would challenge her.

A few years ago, Bjorn and I hiked the 33-mile Chilkoot Trail, the route many would-be miners took to the Yukon during the Klondike Gold Rush. It was before the official start of the season, and except for a very fit German guy in his mid-twenties, we were the only hikers. We spent the first night at Sheep Camp, the last stop before the pass; the German guy woke before us, and we followed his tracks the rest of the day. We summited the pass in a late-May snowstorm on steps Bjorn cut with his ice ax and emerged from the clouds into what a Canadian ranger we’d passed called “a bluebird day.” It was surreal. We were still using our snowshoes, but bumblebees buzzed around us and landed on the snow. We started steaming. We followed the route the snowshoe-wearing rangers had flagged…right over a half-frozen pond. The German guy hadn’t brought snowshoes, and we could see the hole where he’d fallen through up to his waist, the drag marks where he’d pulled himself out. As we walked, we saw his footsteps — he’d been post-holing, sinking through the deep snow up to his crotch with each step. Post-holing makes for incredibly miserable walking. A few miles later, we saw a tiny figure waving to us frantically. The German guy hadn’t brought sunglasses, and his eyes were hurting; he was going snow-blind. Bjorn gave him an extra pair. The rangers had told him they’d marked the trail to Happy Camp, and he was wondering if he’d taken a wrong turn. We got out our GPS and figured out we were on the snow-covered trail, but the rangers had stopped flagging two or three miles short.

That is what happens in wilderness when you are unprepared — even with a flagged route on a trail thousands have walked before, even if you are experienced. You don’t magically find a party-food-filled abandoned cabin decorated for a family reunion, complete with a sheet cake under a protective dome. You end up miserable and wet and exhausted and snow-blind and far from where you’ve tried to be, and if you’re lucky, it’s a sunny day and there are other people around who can help you. It’s a transformative experience to realize how vulnerable, and how lucky, you are.

The idea of owing more to luck than courage, however, contradicts one of the basic themes of Heroes of the Frontier — that through acting bravely and persevering, you and those around you (in Josie’s case, Paul and Ana) can become the “heroes” of the title. That conflict is one of the difficulties of writing wilderness in fiction. Wilderness is what it is, not what a book requires it to be. The Alaskan wilderness challenges people in ways they don’t anticipate, and it is not kind to the inexperienced and underprepared, no matter how “brave” they might be.

Last year, I went to a panel in which Juneau writer Ernestine Hayes, author of Blonde Indian, said “A sense of place arises from the place itself… it is (not) a panorama to be conquered.” I thought of this as I read these lines, after Josie and company arrive at the cabin: “Every part of their being was awake. Their minds were screaming in triumph, their arms and legs wanted more challenge, more conquest, more glory.” At the end of Heroes of the Frontier, Alaska is a panorama conquered.

Last year, I went to a panel in which Juneau writer Ernestine Hayes, author of Blonde Indian, said “A sense of place arises from the place itself… it is (not) a panorama to be conquered.” I thought of this as I read these lines, after Josie and company arrive at the cabin: “Every part of their being was awake. Their minds were screaming in triumph, their arms and legs wanted more challenge, more conquest, more glory.” At the end of Heroes of the Frontier, Alaska is a panorama conquered.

Ultimately, the novel is about a woman escaping the fears, restrictions and regrets of her life and trying to shape her children into good, brave people, like those she imagines live in Alaska. It’s an admirable goal. But both in towns and out of them, Josie, Paul and Ana seem charmed. In the wild, that means Eggers’s Alaska loses something essential to itself.

So here are some questions. Where is the line between artistic license and error? If we take liberties with the character of a place and we are aware of it, should we acknowledge that we’ve done so? This isn’t nonfiction, after all, and in spite of its bighorn sheep, Heroes of the Frontier is an enjoyable story.

Writers who write wilderness have a responsibility to it, partly because so many of us are disconnected from it, and partly because it’s been misrepresented so often. We’ve now constructed so much of the world — even in our national parks — that most of us never experience real wilderness, a place you can’t see from the road. It exists with or without us. It means only and incredibly itself, and when we are there, we become a part of it — something that can be terrifying, or exhilarating, or both.

There is lots of insightful, beautiful writing about Alaskan and northern wilderness, both fiction and nonfiction — see Seth Kantner, Sherry Simpson, Velma Wallis, a vast array of others. There are people who write wilderness gorgeously outside the context of Alaska as well — Louise Erdrich, Cormac McCarthy. If there’s anything wilderness can teach you, it’s the dizzying breadth of what you do not know, and if what you write is to resonate as true there is no lesson more important. So if you’re going to write wilderness, experience it. Respect it. Be prepared and scared and awestruck and relieved. Research. Fact check. Then represent the place you are writing as honestly as you can. You owe it to a world that has lost a sense of true wild.

Image courtesy of the author.