Whatever your feelings about Twilight, you have to admit that the breadth and scope of the Twilight phenomenon is spectacular. Boy wizards aside, literature-inspired hoo-ha of this magnitude just doesn’t come along that often. To begin with, there is the dizzying array of memorabilia: Twilight band-aids, duvet covers, water bottles, umbrellas, jewelry, wallets, life-sized wall decals, as well as the standard t-shirts and movie posters. Kristen Stewart, the actress who plays Twilight heroine Bella Swan in the film adaptations, has expressed astonishment that rather mundane items of clothing she’s spotted wearing sell out in hours. There’s a Twilight make-up line that includes a pinkish gold-flecked lotion that promises to give “Twihards,” and anyone else, vampirically luminous skin (according to the editors of Lucky Magazine, “it’s gleamy but not over-the-top-Edward-in-sunlight-sparkly”). And that’s not to mention the Twilight fan blogs (oh, TwilightMomsBlog!) and the legions of YouTube videos posted by less satisfied Twilight readers burning, beating, and taking chainsaws to their copies of the best-selling novels (Breaking Dawn, the fourth and last book in the series, sold 1.3 million copies in the first day; total sales of all of the books are at upwards of 40 million, and since the final installment came out last year, all four books in the series have remained in USA Today’s top 10 bestsellers). And then there are the sell-out midnight shows whose fangirl audiences reportedly squeal with delight when the lights dim. The father of one of these fans told me that his 14-year-old daughter had taken to signing her text and email messages “Twilight,” instead of her name.

Whatever your feelings about Twilight, you have to admit that the breadth and scope of the Twilight phenomenon is spectacular. Boy wizards aside, literature-inspired hoo-ha of this magnitude just doesn’t come along that often. To begin with, there is the dizzying array of memorabilia: Twilight band-aids, duvet covers, water bottles, umbrellas, jewelry, wallets, life-sized wall decals, as well as the standard t-shirts and movie posters. Kristen Stewart, the actress who plays Twilight heroine Bella Swan in the film adaptations, has expressed astonishment that rather mundane items of clothing she’s spotted wearing sell out in hours. There’s a Twilight make-up line that includes a pinkish gold-flecked lotion that promises to give “Twihards,” and anyone else, vampirically luminous skin (according to the editors of Lucky Magazine, “it’s gleamy but not over-the-top-Edward-in-sunlight-sparkly”). And that’s not to mention the Twilight fan blogs (oh, TwilightMomsBlog!) and the legions of YouTube videos posted by less satisfied Twilight readers burning, beating, and taking chainsaws to their copies of the best-selling novels (Breaking Dawn, the fourth and last book in the series, sold 1.3 million copies in the first day; total sales of all of the books are at upwards of 40 million, and since the final installment came out last year, all four books in the series have remained in USA Today’s top 10 bestsellers). And then there are the sell-out midnight shows whose fangirl audiences reportedly squeal with delight when the lights dim. The father of one of these fans told me that his 14-year-old daughter had taken to signing her text and email messages “Twilight,” instead of her name.

The books have also had a startling effect on the small town of Forks, Washington, the setting of Meyer’s series. Tourism has been booming. Last year, the mayor of Forks declared the weekend of September 12-13th to be Stephenie Meyer Day Weekend (September 12th is Bella Swan’s birthday). This year, the weekend’s events include a birthday breakfast for Bella, tours of Forks High School (where Bella was supposed to have been a student), a Twilight character look alike contest, and a sunset bonfire at the Quileute Reservation, on the same beach where, in the novels, Bella meets Jacob Black, a Quileute teenager, who becomes her best friend, a werewolf, and the rival of the beautiful teenage vampire Edward Cullen for Bella’s affections. By all accounts, this year’s celebration was a massive success, nearly doubling Forks’ population of somewhere around 3,000 and drawing visitors from as far away as England and Japan.

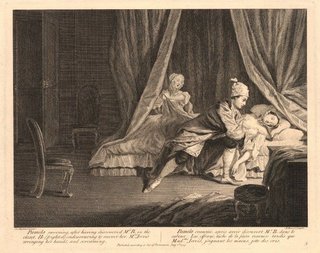

Marveling at all this on the eve of the second Twilight movie’s release, I found myself thinking of Samuel Richardson‘s Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded. Pamela, published in 1740, was the first best-selling novel in English; it is the story of a teenage servant girl who resists her aristocratic master’s increasingly violent sexual overtures, eventually wins his heart and becomes his wife. It was the first novel to inspire the sort of frenzy that Twilight is inspiring right now. Like Twilight, Pamela spawned themed merchandise: Pamela tea cups and tea towels, Pamela prints and painting, Pamela fans, Pamela playing cards. Pastors recommended the book from the pulpit and European intellectuals as well as private citizens sang its praises. Rousseau, for one, reported weeping copiously over it. There wasn’t any declaration of a Pamela Day, but one famous and oft-repeated anecdote about the Pamela mania verges into the kind of confusing of the fictional and the real that the Forks’ Twilight celebrations offer. There are many anecdotes dating back to the eighteenth century, in which Pamela’s wedding is taken as fact or publicly celebrated. In one of the best known, from an 1833 address given by Sir John Herschel at Eton, a blacksmith in a small village in Windsor got hold of a copy of Pamela

and used to read it aloud in the long summer evenings, seated on his anvil, and never failed to have a large and attentive audience…At length, when the happy turn of fortune arrived, which brings the hero and heroine together, and sets them living long and happily according to the most approved rules—the congregation were so delighted as to raise a great shout and, procuring the church keys, actually set the parish bells ringing.

These readers were practicing the English custom of ringing church bells to celebrate and announce a marriage–though in this case, the marriage of a fictional hero and heroine: Pamela and her former master, the landed squire named Mr. B.

Pamela was revolutionary in its day and Richardson was both celebrated (as by the Windsor townsfolk) and reviled for the novel’s “leveling” tendency. Servants and common laborers were widely considered a lesser order of being in the eighteenth century—there to serve the pleasure of their masters, whatever that pleasure might be. The idea of a titled landowner marrying his maid—when he might sleep with her with impunity—was considered scandalous and subversive, to say the least. Historian Lynn Hunt‘s recent book, Inventing Human Rights, claims that novels like Pamela were foundational in the development of the idea of human rights that surfaced explicitly in the French and American Revolutions of the late eighteenth century.

Pamela was revolutionary in its day and Richardson was both celebrated (as by the Windsor townsfolk) and reviled for the novel’s “leveling” tendency. Servants and common laborers were widely considered a lesser order of being in the eighteenth century—there to serve the pleasure of their masters, whatever that pleasure might be. The idea of a titled landowner marrying his maid—when he might sleep with her with impunity—was considered scandalous and subversive, to say the least. Historian Lynn Hunt‘s recent book, Inventing Human Rights, claims that novels like Pamela were foundational in the development of the idea of human rights that surfaced explicitly in the French and American Revolutions of the late eighteenth century.

On the surface, then, it would seem that the similarity between Twilight and Pamela, between Bella and Pamela, ends in their popularity and the mania they inspire(d). But these twin phenomena, one sitting at each end of the history of the novel, I think, share more. By an admittedly cynical and reductive reading, Twilight and Pamela are the same book, the same archetypal female fantasy: a poor or undistinguished girl is chosen as “the one” by a handsome, rich, aristocratic man who sweeps her off her feet and takes her out of her (more or less) grubby, mundane, low-born life. And the cynical reading goes further. These are not merely Cinderella love stories; in fact, they are not love stories at all. By the cynical reading, these novels are only about class, about becoming rich, becoming one of the rarefied beautiful people.

A year after Pamela‘s publication, Henry Fielding published Shamela, a parody of Richardson’s novel motivated by the belief that Pamela didn’t resist her master’s attempts to rape her out of fear or a moral certainty that her desires were just as important as his, but because she thought she might get more out of him if she held out. Fielding’s sham Pamela is a hypocrite, a wily girl on the make—after money, finery, and social position that she was not entitled to by birth or by her incredible virtuousness (which Fielding tells us is only a ruse designed to ensnare Mr. B, her master.). Pamela protests too much on Fielding’s reading: he suggested that Pamela’s belaboring of the spiritual peril that Mr. B’s advances threaten her with, combined with her obvious attraction to him, didn’t quite ring true.

A year after Pamela‘s publication, Henry Fielding published Shamela, a parody of Richardson’s novel motivated by the belief that Pamela didn’t resist her master’s attempts to rape her out of fear or a moral certainty that her desires were just as important as his, but because she thought she might get more out of him if she held out. Fielding’s sham Pamela is a hypocrite, a wily girl on the make—after money, finery, and social position that she was not entitled to by birth or by her incredible virtuousness (which Fielding tells us is only a ruse designed to ensnare Mr. B, her master.). Pamela protests too much on Fielding’s reading: he suggested that Pamela’s belaboring of the spiritual peril that Mr. B’s advances threaten her with, combined with her obvious attraction to him, didn’t quite ring true.

In Pamela’s case, I think Fielding goes too far. A marriage to a landed, titled man would have been quite literally beyond the wildest dreams of a servant like Pamela, even assuming that she possessed the sort of calculating wiliness that Fielding attributes to her. In fact, if she were as wily as Fielding drew her, Shamela would have known that she’d never become Mr. B’s bride. (Only by the rules of Richardson’s quasi-allegorical plot can Pamela’s virtue be rewarded as it is.) But in the case of Meyer’s Bella Swan, I think Fielding’s hypocrisy reading might stand. Like Pamela (and Pamela is more convincing), Bella insists that what she values, particularly in her beloved vampire Edward, is spiritual: “Edward had the most beautiful soul, more beautiful than his brilliant mind or his incomparable face or his glorious body,” she tells us.

But why, if the spiritual is supposed to be paramount, are the Twilight novels so distractingly full of money – literally, piles of cash – and the things money can buy? “There was enough cash stashed all over the house to keep a small country afloat for a decade,” Bella reports of the Cullen family home. This cash buys Bella an acceptance to Dartmouth, a special order Mercedes (a model preferred by drug dealers and diplomats for its bulletproof glass—Edward’s very protective), a Ferrari, lots and lots of couture clothing, and a faux rustic cottage in the woods that I came to think of as a version of Marie Antoinette’s hameau (the little faux farmhouse where the queen and her ladies played at being peasants). All of this, Bella claims to resent or to feel uncomfortable accepting.

But the idea that the Cullen wealth holds no appeal to Bella, when it is Bella herself who draws so much attention to it in her first-person narration, just doesn’t stand. When, at the end of the fourth book, she finally admits a little pleasure in the jaw-dropping, head-turning spectacle that this wealth allows her to become, it feels like she is finally admitting what she’s felt and wanted all along—a pleasure that anyone, most especially a teenage girl, would feel:

He took the calf-length ivory trench coat I’d worn to disguise the fact that I was wearing Alice’s idea of appropriate attire, and gasped quietly at my oyster satin cocktail gown. I still wasn’t used to being beautiful to everyone rather than just Edward. The maitre d’ stuttered half-formed compliments as he backed unsteadily from the room.

Of course, the idea here is that it’s (spoiler alert) Bella’s newly enhanced physical beauty that stuns the man (she’s become a vampire at this point, and vampires are more beautiful in order to attract their prey, i.e. humans), but Meyer/Bella lingers on the clothes—the things money can buy.

Bella’s compulsive observation of the Cullens’ beauty and their beautiful things does not come to seem a metaphor for spiritual superiority but a conflation of material wealth, physical beauty, and moral elevation. While the books suppose to be about a perfect, otherworldly love (this love could be metaphor: it certainly doesn’t exist in the real world), the material intrudes constantly (cars, money, clothes), suggesting that beauty and money and blessedness and happiness are all one, confused and interchangeable.

This pernicious lie that is at the heart of Twilight. When I see pictures of young girls waiting in line to buy these novels or tickets to the movie, this is why I get angry. I don’t get angry because Meyer’s recycled the classic female fantasy of the most desirable boy picking the girl he never will in real life (I love My So-Called Life, while knowing all too well that Angela Chase (Clare Danes) would never have gotten Jordan Catalano (Jared Leto) in “real” life), I get angry because Meyer didn’t seem to trust the unbelievable love between Bella and Edward as sufficient to hold her readers’ interest. Love, apparently, needs to be tarted up in designer clothes, given sparkling six-pack abs, armed with platinum credit cards and Ferraris before we’ll recognize it. For all of its heavy-handed allusions to Romeo and Juliet and Wuthering Heights, Twilight is, in the end, fatally invested in the shallow materialism and the youth and beauty worship that continue to define and corrode American popular culture.

It’s scarier than vampires.