1.

1.

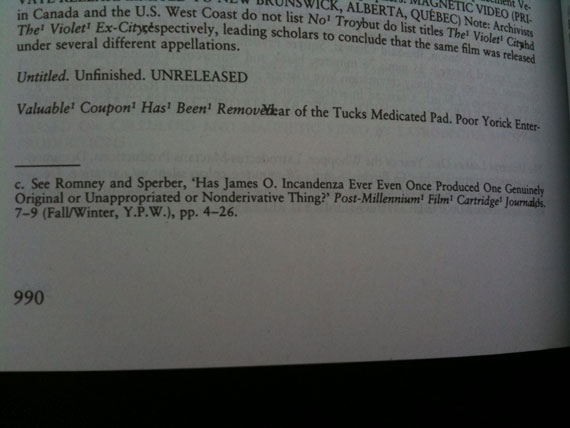

The only footnotes worth reading these days are the ones written by David Foster Wallace. Wallace made the marginalized fine print purr with energy. The typical Wallace footnote is something of a trick. It begins with what appear to be functional intentions before morphing into a linguistic stunt delivered with a sweet mixture of wit and tenderness. When it’s over (and that

can take a while — sometimes pages in 7-pt font), a single Wallace footnote creates shockwaves that reduce the dominant text, no matter how brilliant, to an afterthought.

I’m speculating here, but I’m fairly certain those footnotes probably got Wallace laid. A lot. D.T. Max’s recent (and wonderful) biography is littered with anecdotes documenting the writer’s opportunistic carnality. We learn, for one, that on a fall afternoon, making his way across the

quadrangle of Amherst College, Wallace turned to a friend and noted how “the smell of cunt was in the air.” Seriously. Cunt. Here was this off-the-charts brilliant man, a charming wordsmith who used words such as priapic and supperate as if they were the stuff of bathroom graffiti, reducing garden-variety lust to a word so juvenile in its offensiveness that most decent folk just refer to it, under duress, as “the c-word.”

Say what you will about propriety, but such language bespeaks drive. My introductory claim here is thus that Wallace’s success with women — however fleeting and detached and cold — had something to do with those footnotes. Again, I’m aware that this sounds sort of ridiculous. But think about, as a reader, how a truly good footnote can rivet you to the page and transport you to an exotic fantasyland. It’s the verbal equivalent of wink and a nod, a secret invitation to look under the hood. Wallace footnotes are an exclusive invitation to connect over something more exciting than whatever’s happening above, at that moment, in the conventional living room of common text where words make small talk. It is, alas, an aphrodisiac.

I’m a professional historian. I’m indoctrinated, not to mention professionally obligated, to wonk out on footnotes. But, after two years of studying Wallace’s trail of gems, I’ve stopped reading historical footnotes. Comparatively speaking, they’re beyond painful, about as sexy as grandma jeans, and — as a direct result — a collective foreshadowing of my profession’s slow demise. I don’t mean to sound dramatic here. But I do mean to be clear and confessional and might as well get to it:

I’ve not only stopped reading historical footnotes but, due to Wallace’s footnotes, I’ve stopped reading all academic history. Having been seduced by a real writer’s footnotes, I just can’t do it anymore. I’m well aware that there are very sensible and sober reasons for including historical footnotes, especially when you are writing about, as they are in the current issue of The American Historical Review, “the contingencies of postcolonial history-writing.” I get it. But the critical if reductive fact of the matter is that no historian in the history of writing history was writing history in order to get laid. And that’s ultimately why, I’m afraid, we’re history. Our time has come.

2.

For me, an inveterate novel reader, this conclusion has been marinating for a while. Many novels that I’ve been reading over the past few years — Hilary Mantel notwithstanding — generally express a lingering hostility toward my profession, or at least hostility to what the profession

refuses to aspire to: telling accurate and relevant and entertaining stories about the past with such skill that readers want to sleep with you.

My reading journal alone brims with novelistic expressions of scorn for my trade. There’s Bud’s plea to Lit to cease talking about the past in Charles Frazier’s Nightwoods. He says, “Come on, fuck this shit. What do you care about history? I thought we were friends.” Or there’s Don DeLillo’s time-obsessed narrator in Point Omega, declaring, “An eight-hundred-page biography is nothing more than dead conjecture.” Or consider Julian Barnes’s character Finn, the precocious kid in The Sense of an Ending who, to further stoke the awe of his peers, utters oracular portents such as, “History is that certainty produced at the point where the imperfections of memory meet the inadequacies of documentation.” (And then he gets laid.) Add to the mix Alistair MacLeod’s No Great Mischief, in which Macaulay, the great historian of England, is casually dismissed as a guy “who just made it up after the event.” Such is the novelistic respect for historical thought and writing.

My reading journal alone brims with novelistic expressions of scorn for my trade. There’s Bud’s plea to Lit to cease talking about the past in Charles Frazier’s Nightwoods. He says, “Come on, fuck this shit. What do you care about history? I thought we were friends.” Or there’s Don DeLillo’s time-obsessed narrator in Point Omega, declaring, “An eight-hundred-page biography is nothing more than dead conjecture.” Or consider Julian Barnes’s character Finn, the precocious kid in The Sense of an Ending who, to further stoke the awe of his peers, utters oracular portents such as, “History is that certainty produced at the point where the imperfections of memory meet the inadequacies of documentation.” (And then he gets laid.) Add to the mix Alistair MacLeod’s No Great Mischief, in which Macaulay, the great historian of England, is casually dismissed as a guy “who just made it up after the event.” Such is the novelistic respect for historical thought and writing.

The disparagement of my profession in the pages of modern fiction doesn’t bother me at all. It shouldn’t. It can’t. It’s pretty accurate, for one. For another, it’s ultimately a kids’ gloves treatment. It doesn’t come remotely close to capturing the remarkable depth of the historian’s unmatched capacity to ask questions that evoke drool and then answer them with coma-inducing prose. I’m not exaggerating here. A professional historian (not like those successful amateurs who we simply hate for actually getting people to read history) can drag you into verbal ennui faster than an instruction manual for an Ikea bunk bed. The sad thing is that we were trained to do this. Indeed, we’re creative people dulled by the arbitrary and pinheaded imperatives of professional achievement. The sexy stimulus of storytelling has been leached out of us by comp exams and dissertation writing and Turabian. Wallace, who was smart enough to drop out of a PhD program in philosophy to keep his literary voice untainted, can write a footnote that makes you want to have sex. The historian can write about sex in a way that makes you want to read the footnotes. Who are you banking on for the future?

Thing is, we’re all — historians and novelists and essayists and poets — just weaving yarns. This is our common quest. Still, there’s something about the radically different conventions of narration and permissible flexibility of voice between professional historical writing and other forms of storytelling that turns out to be fatal for the future of history. Good novels make you want to seduce and frolic and celebrate and indulge. Good works of academic history to make you want to drink a vial of hemlock. Which is another way of saying that if novelists wanted to really go after professional historians they could mock us even higher up the ivory tower than we’ve already situated ourselves. Frankly, they should. We’ve earned our marginalization. We’ve practically begged for it: mock us.

Chances are we’ll be too far up to hear you. In fact, it’s almost as if we’ve purposely gone against the grain of what works narratively, detaching ourselves from hoi polloi while posing as their champions. In the nineteenth-century you had historians like Frances Parkman telling heroic and tragic tales about explorers and adventures and nation building and Indian fighting. It was exceptional stuff (even if it was exceptionalism at its worst). If a professional historian wrote like Parkman today he’d be vilified for his attention to simple-minded storytelling and failure to analyze, to deconstruct, to complicate, to . . . ugh! . . .contextualize. Today, all the drive to be sexy has been neutralized by context. F. Scott wrote to win over Zelda. Historians write for tenure. It has been more than 70 years since Walter Benjamin, in his classic essay “The Storyteller,” lamented how “Less and less frequently do we encounter people with the ability to tell a tale properly.” He complained. “It is as if something that seemed inalienable to us, the securest among our possessions, were taken from us: the ability to exchange experiences.” He must have had historians in mind.

3.

Here’s what I would suggest that every young PhD student in history currently begin doing (besides preparing yourself for not getting a job): a) skim works of history but study novels; b) never use the words complicate, contexualize, limn, framework, or rich (as in “The driving analytic motivation is to alternately complicate and contextualize the prevalent effort to limn the rich territory between fiction and fact.”); and c) read Wallace’s footnotes, paying attention to how beautifully he’s trying to seduce you. In essence, no matter what your topic is, no matter how obscure or geeky or peripheral, write as if you were telling a story to win over a romantic interest. To be blunt: write as if you were trying to get laid. You most likely won’t, but at least you will have left behind something useful.

Image via Nick Douglass/Flickr