In 2017, Honey & Wax Booksellers established an annual prize for American women book collectors, aged 30 years and younger. Our goal, at the time, was to expand the popular perception of who book collectors are (and can be) by highlighting original collections built by young women, often without the knowledge or help of the rare book trade. By celebrating their achievements, we hoped to inspire potential collectors to look at their shelves differently, to identify patterns and projects, to think creatively about the aspects of the historical record they might recognize and preserve.

The response to this prize over the past eight years has exceeded all of our expectations. We are inspired by our contestants, and delighted to announce the $1000 winner of the 2024 Honey & Wax Book Collecting Prize:

WINNER:

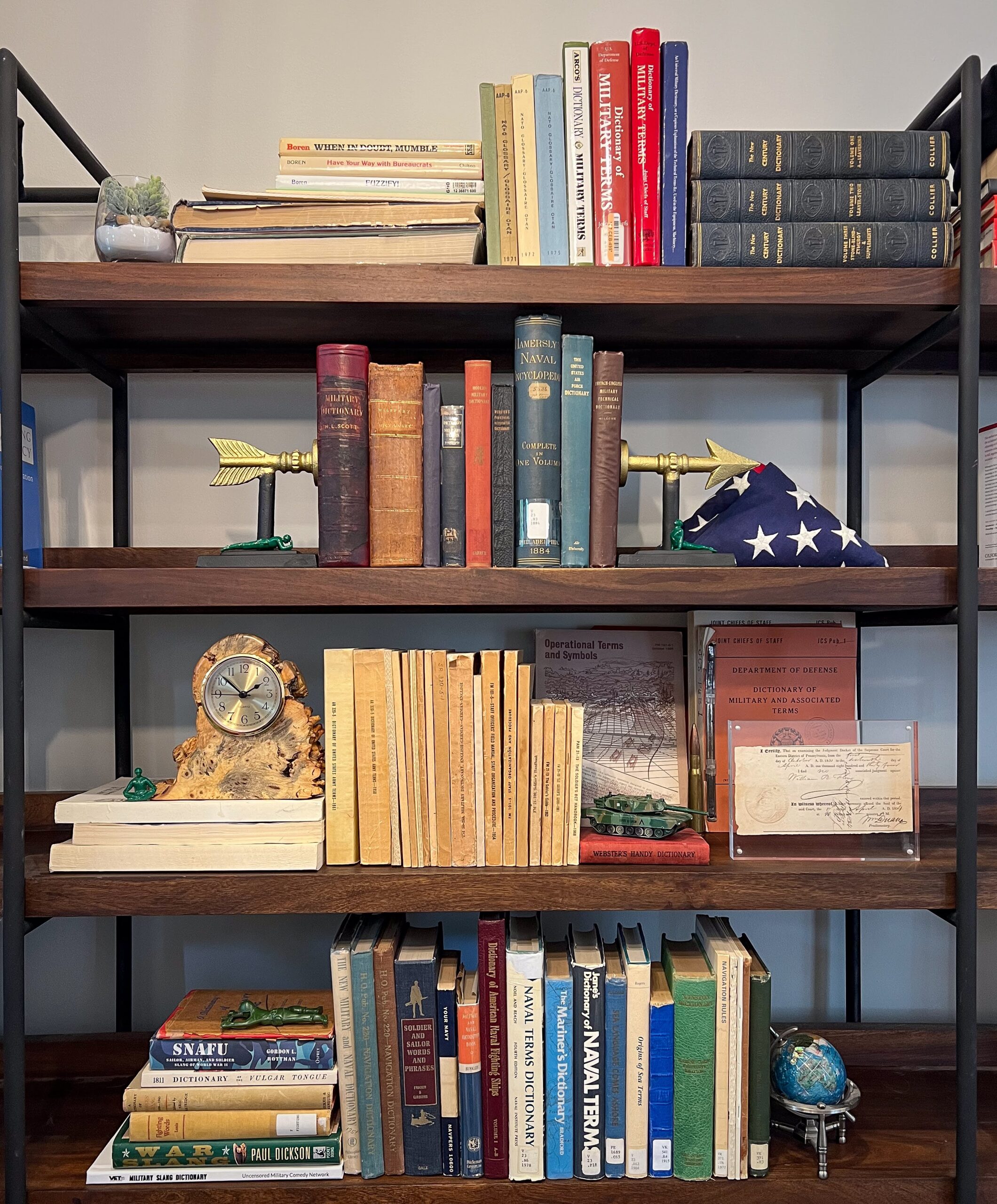

Elena Wicker, 30, (she/her), of Washington, DC, soon to be a national security analyst at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, for “Military Mania: A Collection of U.S. Military Dictionaries from 1776 to Today.”

Wicker first began collecting out of necessity. At her first job out of college, she found herself baffled by the language of her military colleagues: “I had to keep lists of words and acronyms in the margins of my notes for later translation.” That original moment of inquiry grew into a collection of over two hundred American military dictionaries, official and unauthorized, spanning two centuries.

“I began my collection by trying to find the outliers: the first, the last, the biggest, the strangest. Every published dictionary notes which dictionary was now obsolete, or ‘superseded.’ Each book tells you what came before it. I traced each dictionary all the way back to its first edition. The U.S. Army has published over thirty dictionaries, the Department of Defense has published over seventy. I eventually expanded my research to tell the story of the U.S. Navy as well. I collected naval encyclopedias from the 1880s, the famous Jane’s Guide to Fighting Ships from World War II, and lexicons of mariner and naval terms. One of the reasons why I love my collection is because these books weren’t intended for someone like me: a civilian female researcher.”

“I began my collection by trying to find the outliers: the first, the last, the biggest, the strangest. Every published dictionary notes which dictionary was now obsolete, or ‘superseded.’ Each book tells you what came before it. I traced each dictionary all the way back to its first edition. The U.S. Army has published over thirty dictionaries, the Department of Defense has published over seventy. I eventually expanded my research to tell the story of the U.S. Navy as well. I collected naval encyclopedias from the 1880s, the famous Jane’s Guide to Fighting Ships from World War II, and lexicons of mariner and naval terms. One of the reasons why I love my collection is because these books weren’t intended for someone like me: a civilian female researcher.”

We were impressed by the disciplined ambition of Wicker’s collection, pursued within clear national and chronological limits. Her bibliography was exemplary, with close attention paid to the materiality and historical significance of each book, including copy-specific points (a laid-in court document, stamps of the Infantry Journal and the Army Navy Club.) Wicker’s collection reveals a process of continual discovery, using these dictionaries, “invisible observers of history,” to tell a more expansive story about language, politics, and change.

You can read Wicker’s winning essay and bibliography here.

We are also awarding five honorable mentions of $250 each:

HONORABLE MENTIONS

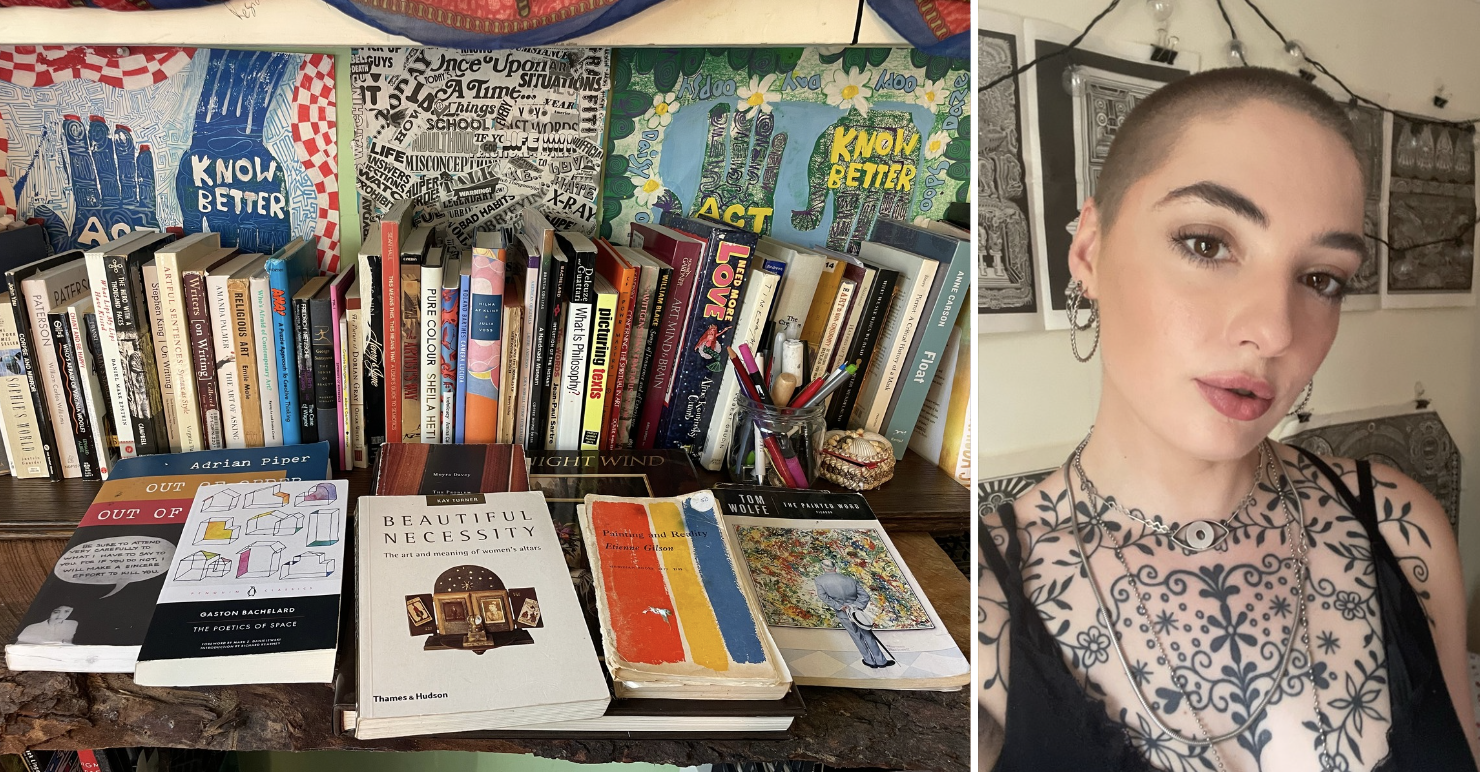

Emily Chauvin, 27, (they/them), an artist and writer from New Milford, Connecticut, for “Theory/Practice: A Meta-Aesthetics Collection.”

Chauvin collects “books of art-about-art,” ranging from William Blake to Yoko Ono, Oscar Wilde to Roland Barthes, George Santayana to Laurie Anderson. While Chauvin concedes that “genre is a blurry game to play,” they focus on books that in some way challenge the divide between aesthetic theory and practice:

“In this collection, each book criss-crosses the fine line between being art and talking about art; at best, they have a foot in both at once. . . . While the deeply academic texts look great on the shelf, I’m more excited by books that have a sense of joy for art. I would love to expand in the direction of comics and graphic novels with a self-awareness of their ‘art-y-ness.’”

We appreciated Chauvin’s definition of their library as “a material history.” Their approach to art as a resource generated all around us, every day, accessible to anyone with eyes to see, is reflected not only in each of the individual books in their collection, which were “90% found, gifted, or thrifted,” but in the creative act of collecting itself.

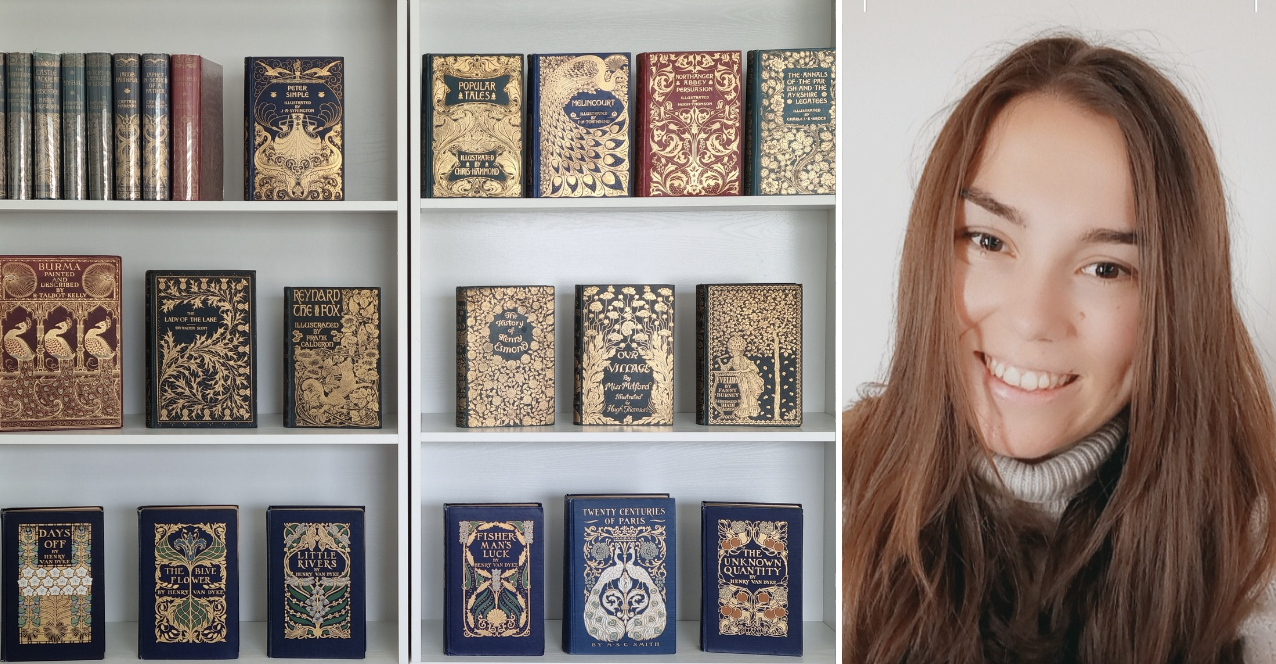

Elena Ganzevoort, 29, (she/her), of Durham, North Carolina, a former book editor, for “Under the Peacock’s Feathers: Discovering Literature through Art Nouveau.”

Ganzevoort collects Art Nouveau publishers’ bindings, including examples by celebrated fin-de-siècle book designers Albert Angus Turbayne and Hugh Thomson. She was drawn to these books at first purely for their design, which reminded her of her years growing up in Paris, walking past Hector Guimard’s Métro stations and other Art Nouveau landmarks. Over time, however, the bindings she collected drew her into a deeper engagement with authors new to her:

“Even though I had initially been simply drawn to these books because of their elegant ornamentation, I became increasingly more fascinated with authors [like Zona Gale] whose names I had never encountered before. . . . Discovering more about female writers steered my collecting interests towards female book artists.”

We enjoyed the organic development of this collection, as Ganzevoort’s interest in book design drew her, gradually, into the text of those beautiful volumes, and the text in turn suggested new Art Nouveau designers to explore, among them Margaret Armstrong and Alice Cordelia Morse.

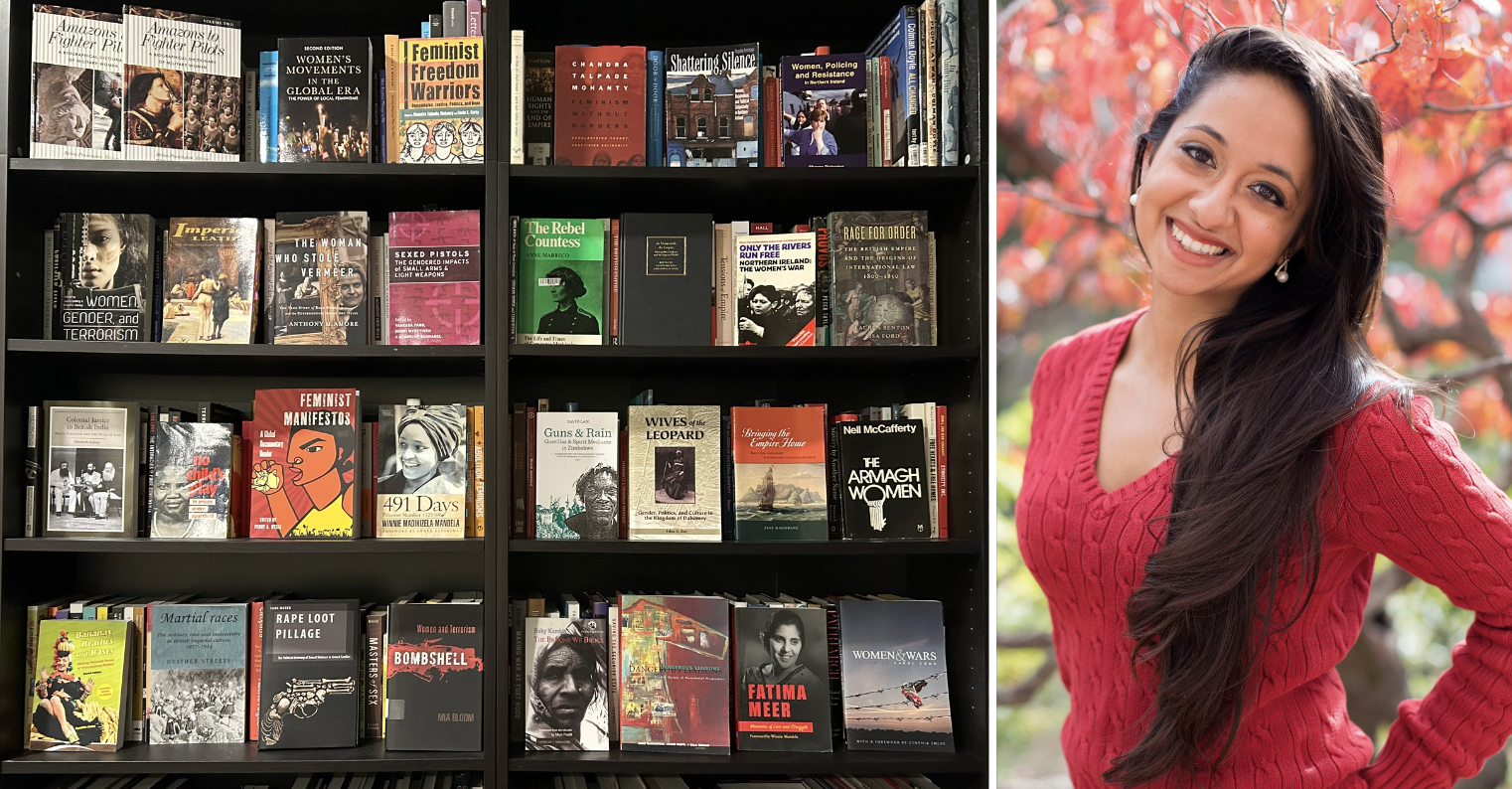

Kirin Gupta, 31, (she/her), a doctoral candidate and teacher in Alexandria, Virginia, for “Femmes Fatales: The Violence and Power of Women Against Empire.”

Gupta collects books by and about women insurgents, guerrillas, and revolutionaries, exploring how gendered expectations shape the way that women’s long-standing participation in political violence is received. While her collection started with scholarly monographs, “over time and with travel, my focus developed. I was able to seek out the stories of the activists themselves.”

“Where the women themselves have narrated these stories, there is so much to be learned . . . such as [in] Nell McCafferty’s The Armagh Women, which captured interviews with the imprisoned women of the IRA during the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The book was banned and burned months after its first small-run publication, only a few smuggled copies making it out of Northern Ireland, so I was thrilled to finally find a copy of this tiny, rare work in Canada.”

We admired the pivot in this collection, from the assembling of an academic bibliography to the pursuit of scarce and out-of-print primary sources, a redirection that centers the historical context of these narratives’ publication and holds the promise of new scholarship.

Donna Sanders, 23, (she/her), of New York City, a recent master’s graduate in English, for “From The Red and the Black to The Man Without Qualities: 101 Texts in 101 Years.”

Sanders approached her collection as a kind of thought experiment, bringing together one reprint of one work of Western literature for every year between 1830 and 1930 to create a three-dimensional mosaic of the long nineteenth century: “I filled in years with all of the glee of a lotto-player scratching off winning numbers.”

“Sometimes great novels doubled up— there are, apparently, bumper crops for exceptional literature— obliging me to choose between two (or three) beloved texts. . . . After laying out one text for every year between 1830 and 1930, I stood back and marveled for some time at the strange bedfellows that popped intermittently into sight. Nietzsche sits by Tolstoy, Lewis Carroll by Dostoevsky, Willa Cather by Vladimir Nabokov!”

We were especially charmed by Sanders’s enthusiasm for her project, and by her highly personal reprint rating system: “smooth over rough-cut pages . . . red Everymen are okay, but black ones are better.” The historical timeline created by these 101 books is overlaid with the history of Sanders’s own experience as a reader, captured in the acquisition notes on each volume.

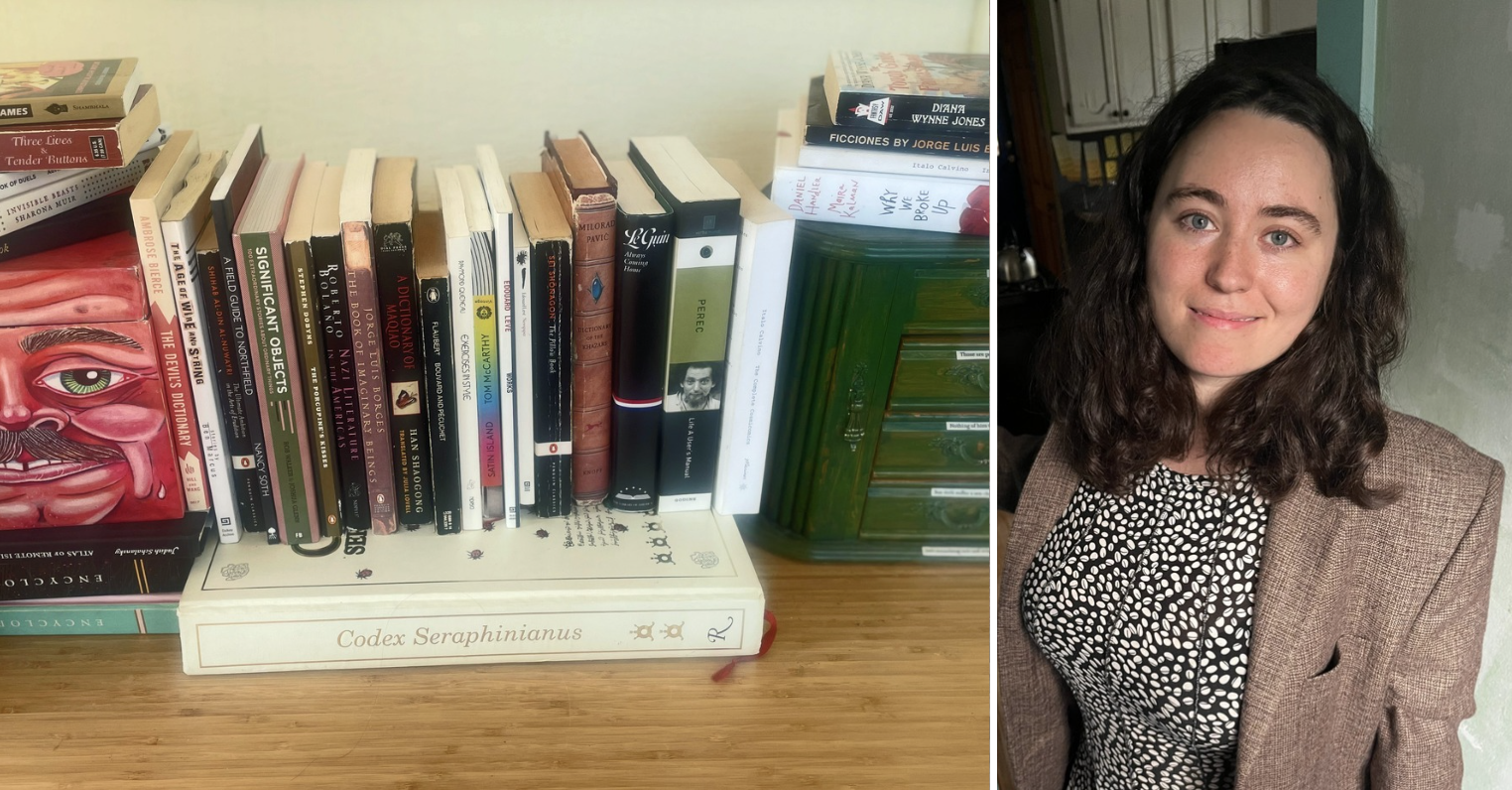

Amelia Soth, 29, (she/her), a freelance writer and editor from Madison, Wisconsin, for “Infinite Fiction: Novels of Classification.”

Soth collects “books that play – in a vast range of ways – with the format of the reference work: the dictionary, the encyclopedia, the catalog, the travel guide, the textbook, the atlas.” Her collection ranges from established classics like Gustave Flaubert’s Dictionary of Received Ideas, Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons, and Jorge Luis Borges’s “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” to more recent works by Milorad Pavić, Sophie Calle, and Roberto Bolaño.

“Paradoxically enough, the literature of classification is itself rarely classified. It remains marginal and under-explored. They aren’t easy to find; there are no commonly accepted search terms (believe me, I’ve tried). As far as I know, I’m the only person obsessed with it. As a result, it’s not really possible for search for these in a concerted way. The only way to find them is to persist, follow your nose, and get lucky.”

We found ourselves immediately invested in expanding Soth’s chosen genre, brainstorming other potential books to add to her collection. We loved the plot twist that, in compiling her bibliography, Soth discovered that her own grandmother had in fact once published a novel of classification.

To see last year’s winners, click here.

The co-founders of the Honey & Wax Prize, Heather O’Donnell of Honey & Wax Booksellers and Rebecca Romney of Type Punch Matrix, would like to thank the 2024 prize sponsors: Biblio, Bibliopolis, The Caxton Club, Christie’s, and Ellen A. Michelson. Thanks also to Lit Hub, Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America, Fine Books & Collections, and The Millions for their support. Most of all, thanks to all the inspiring young collectors who shared their ongoing projects with us! We look forward to seeing where they take you.