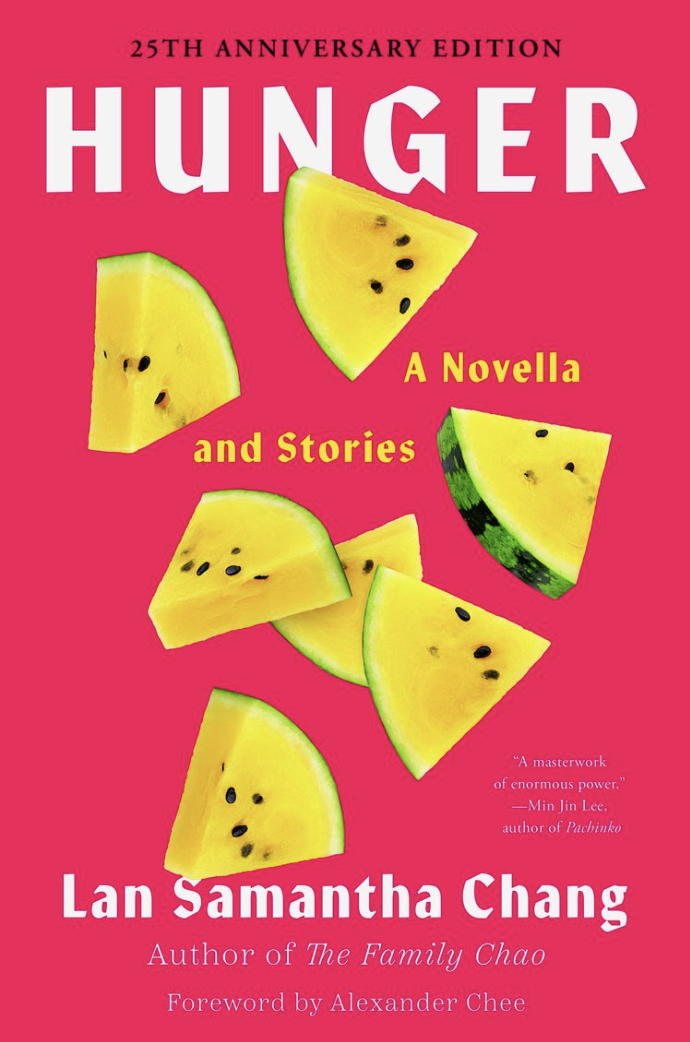

Lan Samantha Chang was a student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop when she wrote many of the stories in her luminous debut collection, Hunger. Published in 1998, Hunger comprises a titular novella and five stories, all filled with exiles and immigrants. Today, the themes of exile and immigration remain central to her work, as the author of three novels and the director of the Iowa Writers Workshop, which she has helmed for the past 17 years. Her new story, “Painting of Hannah,” will be published in Harper’s Magazine later this month.

I spoke to Chang about immigration, competing passions, and Hunger, which has been reissued by W.W. Norton for the 25th anniversary of its publication.

Margot Livesy: I read your collection Hunger with profound pleasure when it was first published and it was a delight to reread it. Many things have changed in your life, and in the larger world, since then, but the stories are just as ravishing, as full of passion and longing, as I remember. I wonder if you’ve reread the collection, and, if so, what that was like.

Lan Samantha Chang: It is so hard to believe it’s been more than 25 years since you were my beloved thesis advisor! And yes, the world has changed so much since then. I recently reread the collection’s title novella, “Hunger,” and was struck by the immigrant characters’ profound isolation in a country that had a much smaller population of Asian Americans than it does now. This is the world before the internet, before social media, when letters and expensive long-distance phone calls were the only communication across continents. Siblings lost touch. Parents died unforgiven.

When I read “Hunger” now, the family’s pain verges on unsustainable. They feel alone in a strange society; moreover, they believe their stories mean nothing. I was struck by Min’s description of her daughter, Anna’s greatest hope and fear—that her childhood home is gone. “This is an echo of my own fear,” Min says, “that there might come a time when no one on earth will remember our lives.” I remember when my family felt so isolated, in Wisconsin, that it seemed to me our story would never be known.

The experience of this isolation is one of the reasons I felt so determined to create a more inclusive program at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. I want to make sure that writers with other stories have the chance to tell them.

ML: Has directing the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, being surrounded by writers at various stages, changed the way you think about writing stories? Your idea of a story?

LSC: When I compare my most recent short story, “Painting of Hannah,” to the stories in Hunger, I see few similarities. Most of those early stories are stark, brief portraits of immigrant families. “Painting of Hannah” is less condensed. It draws upon my evolving interest in artmaking. When I started writing, I was obsessed with the stories of Jewish immigrant families —writers like Bernard Malamud and Philip Roth. I still love these writers—Roth was an inspiration for my most recent novel The Family Chao —but when I was drafting “Painting of Hannah” I had been reading the shorter works of Henry James (“The Real Thing

—but when I was drafting “Painting of Hannah” I had been reading the shorter works of Henry James (“The Real Thing ” and “The Beast in the Jungle

” and “The Beast in the Jungle ”) and Valerie Martin’s collection The Unfinished Novel

”) and Valerie Martin’s collection The Unfinished Novel . I was more consciously interested in creativity, a theme that runs through my work, and which I encounter every day at the Workshop.

. I was more consciously interested in creativity, a theme that runs through my work, and which I encounter every day at the Workshop.

ML: Going back to Hunger, one of the most striking choices in the collection is to begin with the expansive title novella. Was that your idea?

LSC: You may recall my awful struggle with the short story form! Each project felt impossible; there were weeks of three-hour daily writing sessions in which I’d add only a few words. Only the strongest sense of desperation kept me at my desk. I couldn’t see a path as anything other than a writer; and yet, as I mentioned, it seemed the people and the feelings I wanted to write about had never been written about before. I certainly didn’t write the stories with the idea of a collection or even a theme in mind. Four of the stories were written at the Workshop. The novella was drafted years later, in a six-month period. I had failed several times to begin a novel and decided to try something shorter: 100 pages. I had no other goals than page count.

I began “Hunger” with the idea that I’d cannibalize and rewrite one of the short stories, “The Eve of the Spirit Festival,” which is about two sisters and their father. But when I made the father a violinist, the shape of the narrative changed organically, and it became very different from “Spirit Festival.” My biggest struggle was conceiving the point of view; making Min the narrator further transformed the story. When I was done, I had a piercing sense that I had completed a work encompassing everything I’d written over the seven years it had taken me to reach that point. I chose to put it first in the collection, and my editor was supportive.

ML: Growing up, you studied the violin. Was there a moment when you had to choose between writing and the violin?

LSC: Watching my 16-year-old daughter negotiate between an all-encompassing study of violin and the rest of her education as a human being, I have more perspective on my own life as a child musician. I knew I didn’t want to become a violinist—I was practicing, even excelling, only because my mother wanted me to. But I wanted to be a writer. I didn’t have room in my life for more than one obsession. So there was no moment of decision. Instead, the seeds of an interest in a creative practice were planted and, after a long dormant period, have sprouted into a fascination with the world of classical musicians: the ruthlessness of it, and the beauty, as well as the fraught mentorships.

ML: You portray that ruthlessness so vividly. For me one of the most piercing moments in “Hunger” is when the mother tells the father, “You lived an honest life.” “It was never my desire,” he responds, “to live an honest life.” He is lonely twice over, as an artist and as an immigrant.

LSC: I was recently talking to my oldest sister about the indelible marks immigration leaves upon the psyche, marks that can be passed from immigrant parent to child. Although my parents came to the U.S. almost 70 years ago, before I was born; although my family belonged to a wave of Chinese immigration that was followed by several larger waves; although I have identified as an American since childhood, I still feel a connection to other immigrants and children of immigrants. My sister describes what we share as some imprint of “desperation.” I think of it also as the experience of cultural deprivation. This loneliness is essential to all the characters in Hunger: even in “Water Names,” in which three sisters listen to their grandmother tell stories. “Water Names” ends on an awareness of their isolation in the Midwestern landscape. And the story demonstrates how this kind of isolation can lead to the creation of narratives or other art.