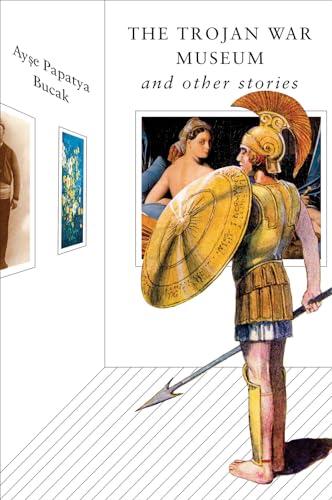

In our latest installment of featured fiction—curated by our own Carolyn Quimby—we present an excerpt from O. Henry and Pushcart Prize winner Ayse Papatya Bucak’s debut collection, The Trojan War Museum: And Other Stories, out today from W.W. Norton.

Kirkus called the book “cerebral yet high-spirited,” while Publishers Weekly, in its starred review, praised Bucak’s “remarkable, inventive, and humane debut.”

“The Gathering of Desire”

It was the age of automatons and already there was a fly made of brass, a mechanical tiger, an eight foot elephant, and a duck that swallowed a piece of grain and excreted a small pellet. There was a dancing woman and a trumpet playing man. A miniature Moscow that burned and collapsed and sprang up again.

And once there was, and once there wasn’t,

in the time when magic was mystery and science was fact,

in the time when God’s hand could arm man’s puppet,

when miracles were seen to be believed, and schemes were believed to be seen,

there was the Ottoman Turk, the chess-playing mechanical man.

Philadelphia, 1827

Outside the Turk’s cabinet is the stage, the audience, and an opponent coaxed out of the crowd by Maelzel the showman. Inside the Turk’s cabinet is the dim light of the candle, its smoke which does not ventilate as quickly as it burns, the magnets and mechanics that allow S. to control the automaton’s movements, the small chessboard that allows him to control the larger game. Outside of the cabinet is all of the mystery and wonder and suspicions that he alone should be free of, the one person who does not have to ponder how it works—inside is a man, him. He is the Turk’s beating heart, he is its brain. Its skill is his, its first move, its reactions, the many wins and few losses, all his. And yet.

Outside the cabinet, the Turk is a champion. Inside the cabinet there are only endless moves, no trickier than the moves S. makes to slide his mechanized seat from left to right, from front to back as Maelzel the showman opens the various doors of the cabinet to prove to the audience that nobody is inside. Maelzel is a master of proving what is not true.

Still there are rumors. A boy, a dwarf, a man without legs. Some have even guessed the truth, mentioning S. by name. And yet the crowds arrive. They will not relinquish their amazement.

They have been performing in Philadelphia a month already when she comes to the stage, the last match of the night. “Never a woman before,” Maelzel announces to the crowd. “Finally a woman. Can she beat the Turk? Can she?”

In the café in Paris, S. sometimes played women, sometimes they flirted with him, but rarely. His appearance was not one to draw women in, nor was his manner. It is no matter: he will play whomever.

Gone are the days of playing masters.

“What is your name, Madam?” Maelzel asks, but S. does not hear her answer.

She takes the stage surprised. She did not mean to volunteer. Her children willed her to, she believes. The power of them together, wishing, with the same force that caused her to take them to the performance in the first place, the first time any of them have gone out since the disappearance (death, she tells herself) of her husband, their father, Thomas, eight months ago.

There have been whispers: another family, a secret debt, a sudden madness. But she does not believe them. Given a mystery, people, she finds, force startling narratives on the unlikeliest characters. Thomas was a Quaker, a teacher and reformer, a person of family; and now people want to believe him less than he was. But she does not care what they want to believe. After all her time in the faith, after all her efforts to hold their community together–it astonishes her to realize it–but she does not care if she sees any of them again. Instead all of her work goes to accepting the most logical truth: she will never know what happened, and Thomas will always be gone. Every day she must convince herself of this or else she will merely pass the time waiting for his return.

Her first look at the Turk is no more than a glance. But when she looks more steadily at him, she wants to laugh—at his height, his fur-lined robes, his ridiculous turban. There is an air of the absurd to the whole occasion, playing chess on stage against an oversized toy–but she finds she feels sorry for him. His dark downcast eyes, painted on of course, make her think of a serious man forced to attend a costume party. He’s sad, she thinks, before she can chase the idea away. He reminds her of Thomas on the occasions when he was forced into society and she was the one to comfort him with the thought of coming home again.

She settles in her seat, arranges her skirts, focuses on the ivory pieces in their familiar formation in front of her. She looks out into the audience, tries to see her children, but all is darkness and shadow.

Thomas Jr. is fourteen, while Margaret is eleven, but in recent months they have twinned themselves. During meals they stare across the table, one at the other, refusing any longer to eat meat and pretending—yes, pretending, she is certain—they are able to communicate without speech. They take long walks by themselves, and force her to wait through long silences before they will answer any question. They all live now in her father’s house; she herself sleeps in the room she had as a child, a strange comfort, and the children have two small rooms adjacent to each other, with a door in between. At night she can hear them talking across the divide, though as much as she strains she cannot make out what they say. During the days they frequently close themselves in one room or the other, and though she stands often outside the door, it is so quiet that she feels forbidden to enter or even knock.

She has thought sometimes of sending Thomas Jr. away to school.

Perhaps she is jealous. They have each other.

But she is their mother; it is grounded in love, her concern.

She herself has stopped going to meetings, no longer calls on anyone, rarely receives calls from anyone; she has refused all invitations for missions and cancelled those that were already scheduled. Perhaps her children’s strangeness is merely a reflection of her own. She cannot seem to move forward in her old life, nor determine how to begin anew.

“Madam will have the first move,” Maelzel says, though she knows that is not the Turk’s custom. It is because she is a woman, she assumes, but she does not argue.

It was Thomas who taught the children chess, and after his disappearance (death, she tells herself) it was her father who taught her, when she and the children moved into his house, when it became clear Thomas was not returning and that she needed both shelter and a job, and her father had, so gently, offered both. Now the four of them play long tournaments, the only thing to reliably keep the children in her presence.

She had thought she was a good mother. Before.

She studies the pieces, imagines the game ahead. She wants very much to win. For them, she thinks, so they will be proud of her. She should find it wrong she knows, to want so much, to be on this stage even, but it is hard to believe now that God would concern himself with such things.

She is embarrassed to see her hand quiver as she raises it over the board, but thankfully only Maelzel is close enough to notice. She glances up at him, and he smiles.

“Do not worry, Madam, he has not leapt at anyone yet,” he announces loudly and the crowd laughs.

How angry people make her lately. She constantly wishes for more grace, but finds herself failing daily at the task of merely being kind. Only her father is still patient with her.

It has been a surprise to her, how grief has changed her.

She takes a breath. Makes her first move. Waits for the Turk to make his.

Excerpted from The Trojan War Museum: And Other Stories. Copyright (c) 2019 by copyright holder. Used with permission of the publisher W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.