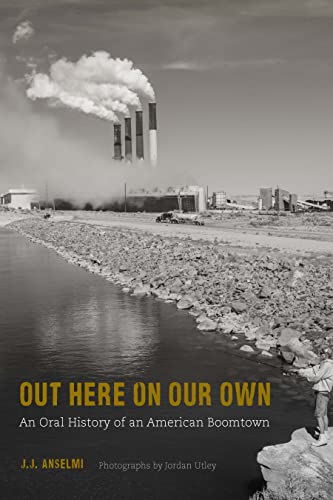

With my first book, Heavy, I wanted to capture Rock Springs, the Wyoming boomtown where I grew up, in all of its grit and glory. Not long after Heavy came out, however, I began to feel like I’d only scratched the surface of the place. The realization was equally daunting and inspiring. I knew I had to write another book about my hometown, but I didn’t know what form it would take. In 2019, three years after Heavy was published, the idea finally struck me: to understand a place like Rock Springs, you need to hear firsthand accounts of what it’s like to live there—and a narrative oral history would be the perfect way to collect those stories.

With my first book, Heavy, I wanted to capture Rock Springs, the Wyoming boomtown where I grew up, in all of its grit and glory. Not long after Heavy came out, however, I began to feel like I’d only scratched the surface of the place. The realization was equally daunting and inspiring. I knew I had to write another book about my hometown, but I didn’t know what form it would take. In 2019, three years after Heavy was published, the idea finally struck me: to understand a place like Rock Springs, you need to hear firsthand accounts of what it’s like to live there—and a narrative oral history would be the perfect way to collect those stories.

Heavy deals with suicide and addiction as cultural norms in mining towns and how that shapes people who grow up in such places—and it’s a project I still believe in. But there are so many aspects of Rock Springs Heavy doesn’t capture, can’t capture, largely because it’s a memoir. For my next book, I wanted to venture beyond my own perspective as much as possible.

These thoughts had been spinning in my head for a few years, but capturing my hometown through oral history didn’t become a concrete notion until I read Mark Yarm’s Everybody Loves Our Town: An Oral History of Grunge. I grew up watching MTV and VH1 and had heard countless stories about grunge emerging in Seattle during the early nineties, and how bands like Nirvana and Soundgarden killed hair metal. But Everybody Loves Our Town was the first book to give me a full sense of what it was like to actually be part of the Seattle grunge scene. It’s told in people’s own words without the filter or spin of narrative journalism. The oral history form asks readers to sift through several stories that don’t neatly align: there are, for instance, multiple, sometimes contradictory accounts of the same events. That sifting process leaves you with a fuller sense of what it was like to be in a specific place at a specific time. I wanted to accomplish the same feat for Rock Springs.

These thoughts had been spinning in my head for a few years, but capturing my hometown through oral history didn’t become a concrete notion until I read Mark Yarm’s Everybody Loves Our Town: An Oral History of Grunge. I grew up watching MTV and VH1 and had heard countless stories about grunge emerging in Seattle during the early nineties, and how bands like Nirvana and Soundgarden killed hair metal. But Everybody Loves Our Town was the first book to give me a full sense of what it was like to actually be part of the Seattle grunge scene. It’s told in people’s own words without the filter or spin of narrative journalism. The oral history form asks readers to sift through several stories that don’t neatly align: there are, for instance, multiple, sometimes contradictory accounts of the same events. That sifting process leaves you with a fuller sense of what it was like to be in a specific place at a specific time. I wanted to accomplish the same feat for Rock Springs.

Once I decided to tell the story of my hometown as an oral history, I was electrified by possibilities. For one, an oral history would let people from marginalized backgrounds speak for themselves, providing much-needed complications and nuance to canonical depictions of Wyoming and the American West. The form would also create space for first-person accounts of life in a mining boomtown during the eras before I was born. The late-seventies energy boom, for example, is notorious in Rock Springs lore for being violent, raucous, and unhinged. That story has been told many times as a straightforward narrative, most famously (and egregiously) by Dan Rather and 60 Minutes. My parents and their friends came of age during that seventies boom. Having grown up hearing their stories, I knew there were so many shades and layers to that era that had yet to see the light of day.

As I began exploring the form, I learned about the distinction between traditional and narrative oral history, which punk chroniclers Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain discuss in a fantastic Lit Hub article on their own book, Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk. There’s a lot to respect about traditional oral histories, like Studs Terkel’s Working, but those collections of interviews don’t usually have the same propulsion of narrative oral histories, in which the interviews are dissected and intertwined.

As I began exploring the form, I learned about the distinction between traditional and narrative oral history, which punk chroniclers Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain discuss in a fantastic Lit Hub article on their own book, Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk. There’s a lot to respect about traditional oral histories, like Studs Terkel’s Working, but those collections of interviews don’t usually have the same propulsion of narrative oral histories, in which the interviews are dissected and intertwined.

I started reading as many narrative oral histories as I could. In addition to Everybody Loves Our Town, I found significant influence—and permission—for my approach in Jean Stein’s West of Eden and Jeff, One Lonely Guy by David Shields, Michael Logan, and Jeff Ragsdale. While I wanted to step beyond my own experience of Rock Springs, I still wanted to be part of its chorus of voices. Both West of Eden and Jeff, One Lonely Guy integrate their authors’ experiences and perspectives, creating a thrilling on-the-ground sensation. Stein and Ragsdale’s gonzo approach to oral history gave me permission to include my own insights into Rock Springs’s boom-bust economy, and to recount my bouts with suicidal ideation in a place where so many people have died by their own hands.

I started reading as many narrative oral histories as I could. In addition to Everybody Loves Our Town, I found significant influence—and permission—for my approach in Jean Stein’s West of Eden and Jeff, One Lonely Guy by David Shields, Michael Logan, and Jeff Ragsdale. While I wanted to step beyond my own experience of Rock Springs, I still wanted to be part of its chorus of voices. Both West of Eden and Jeff, One Lonely Guy integrate their authors’ experiences and perspectives, creating a thrilling on-the-ground sensation. Stein and Ragsdale’s gonzo approach to oral history gave me permission to include my own insights into Rock Springs’s boom-bust economy, and to recount my bouts with suicidal ideation in a place where so many people have died by their own hands.

In addition to including her own experiences growing up in a powerful Los Angeles family in West of Eden, Stein uses historical documents like newspaper clippings, photographs, and quotes from books such as Upton Sinclair’s Oil! to cement gaps in time and narrative. Her book covers the twentieth century in Los Angeles via five of the city’s most impactful families, and there were few living witnesses of the early part of that era when Stein started working on West of Eden, which came out in 2016. I ended up using all those same tactics to complete the historical record.

In addition to including her own experiences growing up in a powerful Los Angeles family in West of Eden, Stein uses historical documents like newspaper clippings, photographs, and quotes from books such as Upton Sinclair’s Oil! to cement gaps in time and narrative. Her book covers the twentieth century in Los Angeles via five of the city’s most impactful families, and there were few living witnesses of the early part of that era when Stein started working on West of Eden, which came out in 2016. I ended up using all those same tactics to complete the historical record.

Armed with inspiration and instruction, I planned to go home and conduct interviews for my oral history in person during the summer of 2020. In addition to the abrupt changes brought on by the pandemic, my wife got pregnant during June of 2020, so the idea of traveling to Wyoming from Southern California (where I now live) was not an option. I decided instead to conduct the interviews by phone. There are purists who believe that interviews have to be done face to face in order to be authentic, but I think conducting interviews over the phone was a conduit for vulnerability, and a significant boon for my project.

One of the first things I did to find people to interview was post on social media and actively reach out to people who I thought might have an interesting Rock Springs story to tell. Having grown up there, I know many families who’ve called that place home, and I had a sense of many of those families’ histories. For as much of a hellscape as Facebook can be (and usually is), it turned out to be a primary way I found people to interview. I also placed an ad in the local newspaper that resulted in a few powerful conversations. Finally, I asked each subject to put me in contact with anyone else who might want to talk to me.

As for phone interviews benefitting the project, I don’t think people would have felt as comfortable sharing such intimate and profound stories as they did if we had talked in person. Maybe that’s self-justification, but as people told me about what it was like to grow up as a Black person in rural Wyoming, or their experiences fighting against a relentless flood of violent heteronormativity, or the despair they’ve felt living in a place with such a high suicide rate—I couldn’t help but feel like such vulnerability and honesty would’ve been harder to achieve in person. On the phone, there’s no eye contact to maintain, no anxiety about being watched, or self-consciousness over facial expressions or body language. Each phone call became its own confession booth. And on a personal level, those conversations provided crucial points of human connection during the stark isolation of the pandemic.

Listening to and transcribing such intense stories, I felt time and again the weight of people’s trust in me to put their stories into the world. It was a different level of writerly responsibility than I’d ever experienced, which was both terrifying and exhilarating. There’s something to be said for taking ownership of a story and writing without fear. But that type of writer-centric approach, while valuable for other projects, wasn’t an option for this one.

Covering the early days of Rock Springs via oral history was its own unique challenge. If I was writing a historical narrative or memoir, something like Hillbilly Elegy (a few literary agents later suggested I use that approach instead), depicting the founding era of the town would’ve been much simpler, a matter of research and exegesis. But I needed first-person accounts. Thankfully, West of Eden showed me how to tackle that problem. In my research, I discovered powerful first-person historical documents and two local memoirs, Thomas Cullen’s Rock Springs: Growing Up in a Wyoming Coal Town 1915-1938 and Marilyn Nesbit Wood’s The Day the Whistle Blew. The publishers and surviving family of those writers were generous enough to let me use significant excerpts from both books.

Covering the early days of Rock Springs via oral history was its own unique challenge. If I was writing a historical narrative or memoir, something like Hillbilly Elegy (a few literary agents later suggested I use that approach instead), depicting the founding era of the town would’ve been much simpler, a matter of research and exegesis. But I needed first-person accounts. Thankfully, West of Eden showed me how to tackle that problem. In my research, I discovered powerful first-person historical documents and two local memoirs, Thomas Cullen’s Rock Springs: Growing Up in a Wyoming Coal Town 1915-1938 and Marilyn Nesbit Wood’s The Day the Whistle Blew. The publishers and surviving family of those writers were generous enough to let me use significant excerpts from both books.

Dissecting original interviews and outside sources and honing the pieces into a cohesive narrative is akin to creating a collage. Or maybe clay sculpture is a better analogy, as the interviews were raw material I had to combine and shape. But it was living and breathing clay, and none of it really belonged to me, so I had to be ever mindful of context and speaker intent. As I shaped what would eventually become Out Here on Our Own, there were several times when I realized it should be done in a different way, at which point I would shatter the sculpture and start anew.

When I finally had something resembling a book, I pitched Out Here on Our Own to multiple literary agents. I knew an oral history of a mining boomtown would be a tough sell to mainstream publishers, but it was still surprising to get responses like, “We think this is a powerful story but not the right way to tell it.” By that point in the process, though, I knew in my bones that an oral history was the only way to tell this story, and I eventually found an editor who recognized that same truth. The form not only enabled me to unearth hidden layers of Rock Springs, but challenged and reshaped my own understanding of the place where I was born and raised. I finished the project feeling more thankful to have grown up there.