Like a lot of the people I know these days who grew up wanting to be writers, I learned how to write by reading the Internet. I graduated from college with a degree in capital-L Literature, but by the time I was 23, my major sources of inspiration were blogs and online fiction magazines. I found my voice (or at least a voice) by imitating bloggers no one had ever heard of, and publishing on websites few people would ever read. This suited me — I liked the isolated weirdness of writing into the infinite void of the web. It didn’t matter to me that no one answered back.

Some time between then and now, businesses with real money caught on to writing on the Internet, discovered it could be made scaleable, and everything changed. For many of my writer friends, this change was a net positive. Suddenly there was money in writing; in some cases, lots of it. The possibility of a “piece” going viral also meant the possibility of a job for pay at a real publication, or a book deal, or a mention in The New York Times, or any number of other writerly blessings. At the same time, wanting to make a career in letters and not being on Twitter and Facebook — that is, not wanting to share your work constantly with the strangers you met on airplanes and in restaurants and people you hadn’t seen since seventh grade — became the equivalent of not actually wanting to be a writer at all. For extroverts and writers with surplus self-assurance this didn’t pose a problem. For those of us drawn to writing because it was the one job that wouldn’t require us to talk to people regularly, it was a nightmare.

“Aside from issues of life and death, there is no more urgent task for American intellectuals and writers than to think critically about the salience, even the tyranny, of technology in individual and collective life,” wrote Leon Wieseltier last month in his call to arms against the threat technology poses to humanism. “Among the Disrupted” sparked a heated debate among its readers, or at least, as heated as can reasonably be expected in the letters section of the New York Times Book Review. As one critic pointed out, there are plenty of more urgent issues for all of us to ponder, child poverty and the pay gap among them. What struck me, though, wasn’t the essay’s hyperbole, but the inaccuracy of its target.

The problem facing writers now isn’t the growing prominence of tech, but the question of how deeply the two fields are intertwined, and what that relationship means. Most of the notable works of fiction published in recent years (Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad and Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven spring immediately to mind) present thoughtful considerations of the evolving relationship between the self and technology, and a lot of the people who read these books probably read them on the Kindle app. The same people who subscribe to Harpers read work published by the Atavist and curated by Longform. I’m writing right now in the notepad app on my iPhone, and you’re reading on your computer or your iPad or your own phone. How many writers do you know at this point who don’t have their own websites, Tumblrs, or blogs? For that matter, how many do you know who aren’t on Twitter?

The problem facing writers now isn’t the growing prominence of tech, but the question of how deeply the two fields are intertwined, and what that relationship means. Most of the notable works of fiction published in recent years (Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad and Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven spring immediately to mind) present thoughtful considerations of the evolving relationship between the self and technology, and a lot of the people who read these books probably read them on the Kindle app. The same people who subscribe to Harpers read work published by the Atavist and curated by Longform. I’m writing right now in the notepad app on my iPhone, and you’re reading on your computer or your iPad or your own phone. How many writers do you know at this point who don’t have their own websites, Tumblrs, or blogs? For that matter, how many do you know who aren’t on Twitter?

Still, it’s true that while the Internet augmented journalism, creating jobs for newcomers and inventing new forms for them to occupy, it didn’t do the same for fiction. Atavist Books confirmed last fall that it would no longer be taking new submissions, and Byliner was folded into Vook last September. Amazon’s e-books are popular, but more innovative forms of digital literature don’t seem to be. Meanwhile, more and more often, walking into library near the office building where I work in Los Angeles feels like walking into a museum. Untouched contemporary novels line the shelves, positions unchanged. The few people in the reading room are, to a person, on laptops or on their phones.

“Only connect,” E.M. Forster wrote in Howards End. We’ve taken his directive and run with it, to the point where we talk about disconnecting — going off Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Venmo, whatever — in the same wistful tones we once used to talk about going on vacation. Social media, like literary fiction, allows us briefly, to inhabit a consciousness outside our own: on Facebook, we experience the highs and lows of strangers in real time through the same lens of authenticity that marks work by writers like Ben Lerner and Sheila Heti. If these platforms give every one of us both an audience and a show on demand, at any given moment, and for free, then what is there left for fiction to do?

“Only connect,” E.M. Forster wrote in Howards End. We’ve taken his directive and run with it, to the point where we talk about disconnecting — going off Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Venmo, whatever — in the same wistful tones we once used to talk about going on vacation. Social media, like literary fiction, allows us briefly, to inhabit a consciousness outside our own: on Facebook, we experience the highs and lows of strangers in real time through the same lens of authenticity that marks work by writers like Ben Lerner and Sheila Heti. If these platforms give every one of us both an audience and a show on demand, at any given moment, and for free, then what is there left for fiction to do?

Curious about how all of this was affecting those most likely to suffer from its consequences, I reached out to novelists in my Twitter timeline to find out what they thought about the role of social media — specifically Twitter — in their own writing lives. I expected all three of them to share my own anxieties — my view of the world has more in common with Wieseltier’s than I am, perhaps, ready to accept — and I was surprised when not one of them did.

Roxane Gay contributes reviews and cultural criticism to high-profile outlets regularly, edits multiple literary journals, and works as a professor at Purdue. She tweets prolifically to her 54,000 and counting followers, and engages with many of them directly. Last year, her essay collection, Bad Feminist, and her novel, An Untamed State, both dropped at the same time, to widespread acclaim.

Roxane Gay contributes reviews and cultural criticism to high-profile outlets regularly, edits multiple literary journals, and works as a professor at Purdue. She tweets prolifically to her 54,000 and counting followers, and engages with many of them directly. Last year, her essay collection, Bad Feminist, and her novel, An Untamed State, both dropped at the same time, to widespread acclaim.

“Many of my essays begin as conversations on Twitter, where I am thinking through something that’s happening in our culture,” Gay wrote me, adding that she uses Twitter “to be alone while feeling less lonely.”

“Ninety percent of the time,” Gay wrote, “I’m having delightful conversations and interactions on Twitter. There’s little to dislike.”

Amelia Gray, author of Threats and the forthcoming Gutshot, responded that Twitter “has been more beneficial to my creativity than most theory,” adding, “It’s a little corner of the world that is a pure ball-pit.” She went on, “My tweets and my fiction ideally share the same precision. They share a sense of character too, though rarely the same character. I use different social media towards different ends, and in that way I have different Internet personas and also a real persona which is different here and there.”

Amelia Gray, author of Threats and the forthcoming Gutshot, responded that Twitter “has been more beneficial to my creativity than most theory,” adding, “It’s a little corner of the world that is a pure ball-pit.” She went on, “My tweets and my fiction ideally share the same precision. They share a sense of character too, though rarely the same character. I use different social media towards different ends, and in that way I have different Internet personas and also a real persona which is different here and there.”

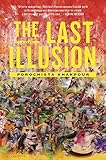

Porochista Khakpour is an essayist and fiction writer and the author of, most recently, The Last Illusion. Last year one of her tweets caught the attention of Slate, landing her timeline a mention in The New York Times Book Review. She often writes, more or less jokingly (I think?), about being enslaved to Twitter, but when I wrote to ask her about the relationship between the site and her work, she wrote back, “I think I am beneficial and destructive to my own creativity and ability to be productive. I am the problem!” She described her relationship to Twitter as, “Love/hate, but tbh mostly love. And we all know love hurts, love bleeds, love kills, love is a battlefield, etc.”

Porochista Khakpour is an essayist and fiction writer and the author of, most recently, The Last Illusion. Last year one of her tweets caught the attention of Slate, landing her timeline a mention in The New York Times Book Review. She often writes, more or less jokingly (I think?), about being enslaved to Twitter, but when I wrote to ask her about the relationship between the site and her work, she wrote back, “I think I am beneficial and destructive to my own creativity and ability to be productive. I am the problem!” She described her relationship to Twitter as, “Love/hate, but tbh mostly love. And we all know love hurts, love bleeds, love kills, love is a battlefield, etc.”

A blogger friend of mine once called social media a loneliness eliminator and I have to admit that definition makes me uneasy. What about those of us who like being lonely? What if loneliness is, in some ways, necessary? It’s true though, that, soon enough, this conversation will likely be irrelevant. Twitter and Facebook will dissolve into the digital slurry, only to be replaced by some other technology as incomprehensible to us as texting once was to our grandparents. Consider Vine, currently churning out new waves of celebrities that no one over 27 has ever heard of. Maybe six-second videos will become the new Twitter, which is the new Facebook, which was the new books. Or maybe, by this time next year, we’ll be having this same conversation about yet another new technology we can never remember how we lived without. Meanwhile, as these writers make clear, fiction writers will continue to adapt, and books, while they may be still hanging on by a thread, will hang on nonetheless.

Something I’m starting to suspect is that it’s everything I worry will make books obsolete — their slowness, the investment of time they require, and their inability to do anything other than the singular purpose for which they’ve been created — that has allowed them to survive for this long. Social media lends itself best to chronicling discrete instances: bursts of anger, flashes of surprise. Built on the notion, even on a micro scale, of constant disruption, our feeds and streams can’t cohere for long enough to bleed seamlessly into one another the way actual sentences do. Twitter and Facebook are great for quick blasts of dopamine or adrenaline, but not for creating sustained waves of happiness or fear or maintaining the kind of cumulative tension upon which good stories rely.

“Only connect!” Forster wrote, but he also wrote, “Live in fragments no longer.” Human experience is like a Georges Seurat in that it only comes into focus the further away you get from it. Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram regurgitate the present back to us in easily manageable pieces that delight, spark envy, disdain, boredom, revulsion, or inspiration. What they can’t do, however, is take a wider scope. Its novels we depend on to reorganize those scattered fragments into something whole.

Image Credit: Pixabay.