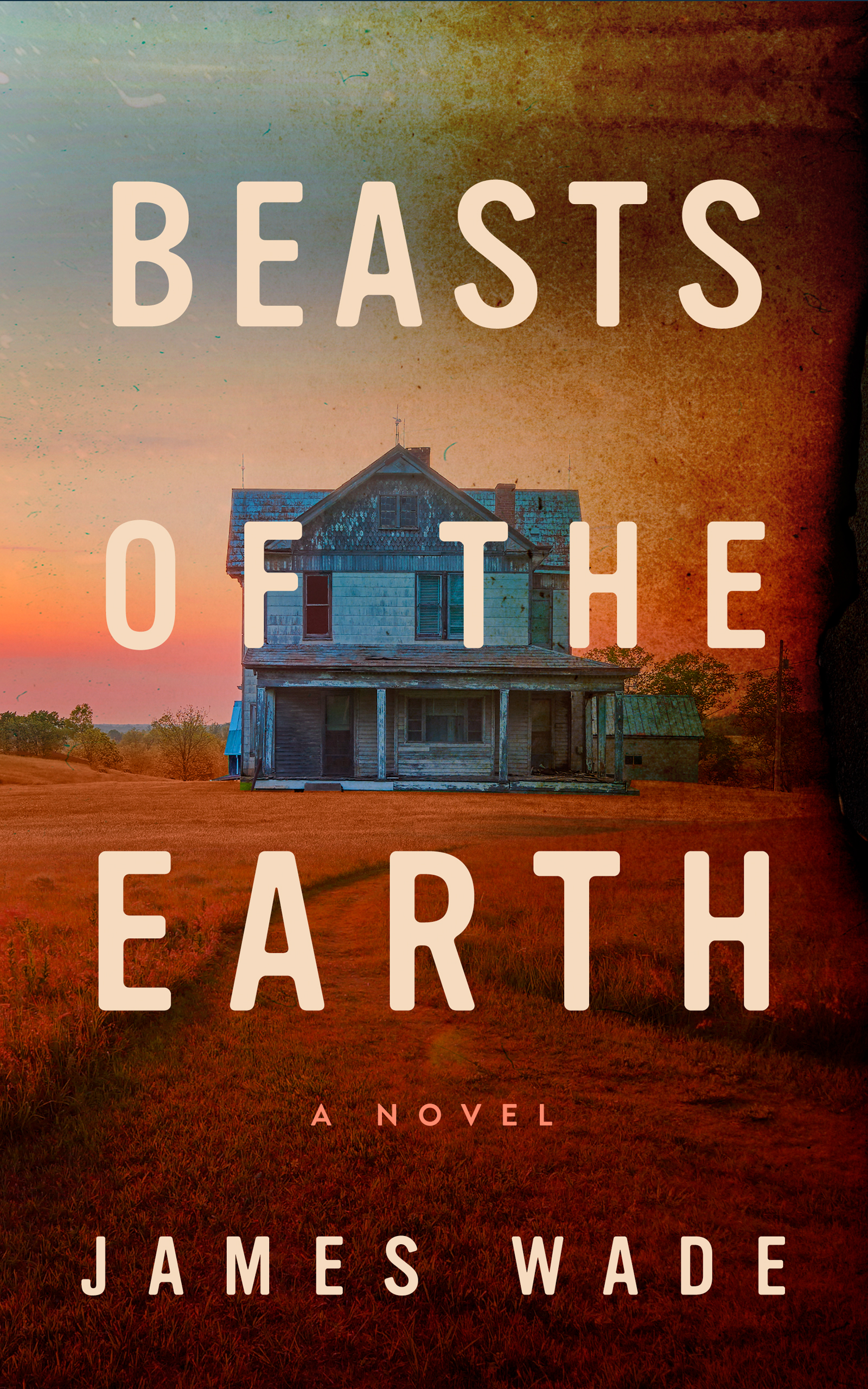

James Wade, whose work has been hailed as “rhapsodic” and “haunting,” is back with his third novel, Beasts of the Earth, a book that explores trauma, love, hate, free will, and everything in between.

Beast of the Earth, set in Texas and Louisiana, weaves together parallel narratives, the first following the life of Harlen LeBlanc, a groundskeeper at Carter Hills High School, whose life is disrupted by an act of violence. The second centers on a young man named Michael Fischer, who is dreading his father’s return from prison.

Library Journal hailed the book as a “stark and chilling tale,” and Wade’s writing has been compared to that of Cormac McCarthy and Flannery O’Connor. The Millions caught up with Wade to talk about Beasts of the Earth, his literary influences, the limits of labeling fiction, and a whole lot more.

The Millions: Beasts of the Earth explores large, complex themes like fate, free will, and what it means to be human. What do you hope readers take from the book?

James Wade: It’s a tough book, there’s no doubt about it—there’s some dark thematic material, some uncomfortable questions. But I think that lends itself to the book’s ability to get inside of you and poke around, which is something I always look for as a reader and as a writer. I hope the folks who read this book will also feel it, and that they’ll let it stay with them. I hope they’ll take something from it—something beautiful or tragic or ponderous—and just grab hold of it and let it be there with them for a while.

TM: The novel weaves together two storylines set decades apart. How did you come to structure the book in that way?

JW: Initially, Michael’s journey was going to be told much quicker in a few italicized chapters sprinkled throughout the novel (much like the structure of Mr. Carson in River, Sing Out). But the more I formed his character, as well as some of the characters he encounters—particularly the dying poet, Remus, and his lover, Deacon—the more I realized it needed to be on equal footing with Harlen’s story. At that point the goal was mirroring the storylines so that they rose and crescendoed at the same pace, so that both Michael and Harlen were simultaneously faced with these difficult decisions at the novel’s climax.

TM: Your characters—both Harlen LeBlanc and Michael Fischer, as well as the characters in River, Sing Out and All Things Left Wild—could be described as tragic or broken. Can you talk a little about writing these sorts of damaged male characters?

JW: I am a damaged male character. Write what you know, right? All of my characters end up dealing with trauma. Usually an abusive parent, or an apathetic one—sometimes both. They all grow up in poverty. They all face a crisis of faith, a loss of innocence. And they’re all stuck in a world they don’t understand but have to continually try making sense of. That doesn’t feel far off from myself or many other folks who struggle with the curse of realism.

TM: How does Beasts of the Earth stand in relation to your two previous novels, River, Sing Out and All Things Left Wild?

JW: Craft-wise, it’s tighter. The word count is smaller and the plot moves quicker. Thematically, it’s similar. I don’t believe I’ll ever be able to tell a story without involving questions of creation, purpose, and choice. And while the setting is still a strong component, Beasts of Earth is a bit more character driven than the previous two.

TM: Your work has been described a Southern fiction, but also as transcending that label? How would you categorize your work? Or do you find labels like Southern fiction and literary fiction limiting?

JW: I find most labels limiting. I think the narrowing of genres into these niche, micro-genres (grit-lit, neo-western, etc.) does a disservice to readers and writers. That said, Literary Fiction, and even Southern Fiction (or Southern Gothic) to a degree, are not as narrow in scope as some others.

TM: Your books are set in striking, singular places. Can you talk a little about the role setting in your work and how a place can function almost like a character?

JW: Setting is absolutely a character, and a strong literary device. It can impact the tone, the conflict, and the themes of a novel, just like any other character or literary tool. For example, half of Beasts of the Earth takes place in the swamps of Louisiana where dark deeds are hidden by the cypress canopies and the black water, and the reader gets a claustrophobic feel in those sections. That’s juxtaposed against the wide open Texas Hill Country where the past is laid bare for the world to see. There is a strong sense of place to each one, but these settings also function metaphorically: the burying of our sins, and the subsequent excavation.

My reverence for setting means I’ve never written about a piece of land I haven’t stood on. I need to experience the country—see the flora and fauna and all that the land entails—before I’m comfortable writing about it.

TM: How did you come to writing? When did you know you wanted to be a novelist?

JW: I started out as a writer when I was a kid. Indiana Jones fan fiction. Civil War short stories. I wrote all the time. And this was really early on– six, seven, eight years old. In my teenage years I was convinced that journalism would save the world. It was during the Iraq War and I became heavily involved in politics and civil service. I pursued journalism and politics for a while in my twenties, but the vitriol and partisanship left me dejected and jaded. And then fiction tugged at my elbow. It was still right there where I’d left it all those years ago—only now I wasn’t some six-year-old prodigy. I had a lot to learn, and I’m still very much learning it. But I hope I’m able to continue learning and continue doing this forever, because now that it’s here, I can’t imagine doing anything else.

TM: Your novels have been compared to the work of Cormac McCarthy, Flannery O’Connor, Larry Brown, and Tom Franklin. What books or authors are particularly important or influential to you?

JW: All of those authors you mentioned, with the addition of Thomas Wolfe, William Faulkner, William Gay, John Steinbeck, and plenty of other dead folks. I do read contemporary fiction, and even occasionally enjoy it. Taylor Brown and Matt Bondurant come to mind as current writers who make me jealous.

TM: Can you tell us a little about your writing process and routine?

JW: The routine was once a well-oiled machine of coffee, reading classic literature, then writing for three to five hours. Every day of every week of every month.

The last couple of years have been a little more challenging. I have a two-year-old daughter who dictates much of what my schedule looks like. Basically, I write when I can—sometimes very early, sometimes very late. And certainly not every day.

The process is usually sketching out a handful of ideas for plots—seeing how those fit into the themes I want to write about. I’ll maybe write a chapter or two and see if the character is someone I think I’d like to spend the next year or so with. Once I pick something, I make a loose outline and dive in.

TM: What are you working on now?

JW: I’m in the editing process on my fourth novel, Hollow Out the Dark, a prohibition, depression era story set in East Texas. It follows a reluctant bootlegger who is trying to protect his surrogate family and his old high school flame from local outlaws during a whiskey war.

And I’m early in the drafting process on a new manuscript that takes place on a Central Texas ranch around 1920.