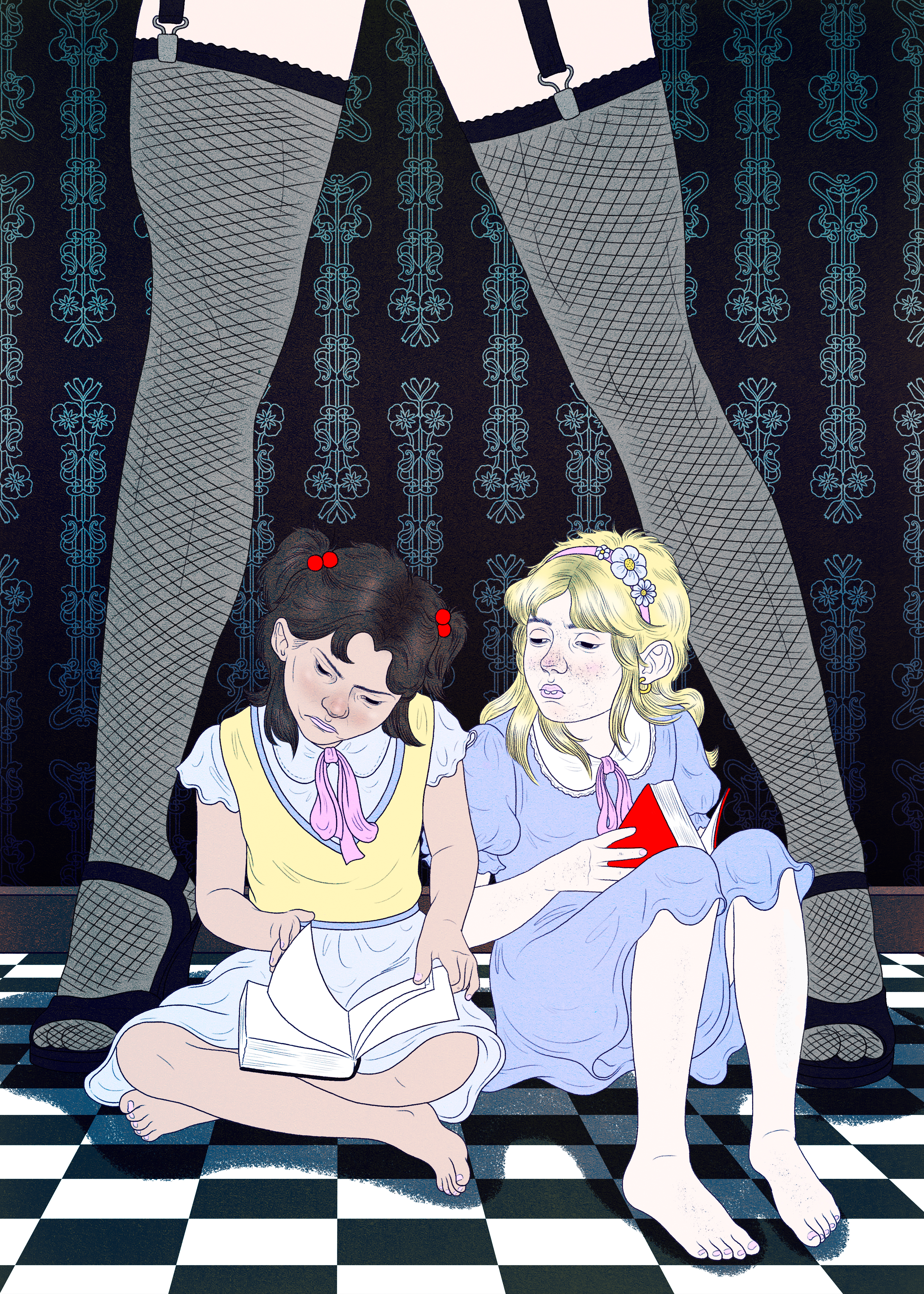

It was in sixth grade that I discovered The Official Rocky Horror Picture Show Movie Novel. During recess a thin, lonely girl named Carrie was hunched in a corner of the playground reading it with rapt attention. An avid reader myself, I was curious and went over to her. I hadn’t heard of the movie. We were way too young to get in, of course.

I was fascinated. The book’s black cover bore the iconic red, dripping-blood letters. It had stills from the film slapped together in bulletin-board style, with dialogue and lyrics. Pictures of Janet in a bra and Frank N. Furter in a sparkly black corset and lush, black-lined lips. You could follow along as you listened to the soundtrack.

Before then it had mostly been Narnia for me. And other children’s classics. We didn’t have a TV, so I wasn’t much of a pop-culture kid.

Before then it had mostly been Narnia for me. And other children’s classics. We didn’t have a TV, so I wasn’t much of a pop-culture kid.

I don’t know how I got my own copy. I only know I read it into rags. It was Frank N. Furter who compelled me most. Even now, when Tim Curry pops up in some small role in a newer movie, I can’t help wishing I could slap that thick, extravagant makeup right back on him. His face—an interesting face, admittedly—looks naked without it.

How I learned the music I don’t know either, because I didn’t have a Walkman till high school and the only record I owned was Supertramp: Breakfast in America. I have a terrible long-term memory, so I also don’t know when I first saw the movie—by then the book had been a beloved substitute for years. Yet to this day I know all the Rocky Horror songs by heart.

How I learned the music I don’t know either, because I didn’t have a Walkman till high school and the only record I owned was Supertramp: Breakfast in America. I have a terrible long-term memory, so I also don’t know when I first saw the movie—by then the book had been a beloved substitute for years. Yet to this day I know all the Rocky Horror songs by heart.

That dog-eared, faded paperback with unglued pages sticking out languished in my childhood bedroom when I went off to college. After graduation I picked it up and moved it with me. To Los Angeles, North Carolina, New York.

A year ago my 14-year-old daughter saw the teen-oriented remake. It was weird and campy, she said. Made no sense. Still, she liked the music. I hurried to fetch the book to show her, but it was nowhere on my shelves.

I must have become ashamed of it at some point, I realized. That was typically why I got rid of old possessions, in my late twenties. Putting away childish things. I cursed my twenty-something self.

I wanted it back. And that’s the thing about lost books—those that aren’t rare, at least. In the world of digital commerce, copies are easily acquired. A replacement wouldn’t be my book. But it would serve.

When the replacement arrived, my daughter glanced at it in passing, shrugged, and said she’d already seen the movie. The original, as well as the remake. The work of a few clicks, $3.99. She hadn’t bothered to ask for permission: it was a given.

Thanks, she said, but she didn’t need to look at the book.

Excerpt from Lost Objects: 50 Stories About the Things We Miss and Why They Matter, available July 26 from Hat & Beard Press.

Illustration by Berta Vallo, a Budapest-born illustrator and graphic designer based in London. Her work has attracted clients such as the BBC, Vice, Bloomsbury Publishing, Financial Times, and Stansted Airport, among many others; and it was featured in Taschen’s The Illustrator: 100 Best From Around the World (2019). Visit bertavallo.com, or follow her via Instagram: @bertavallo.