Great essay collections are generative, both extending and deepening the original reading experience of each individual essay. I’ve been moved by the power and grace of Phil Klay’s fiction, but Uncertain Ground: Citizenship in an Age of Endless, Invisible War, his new collection of essays, is an exercise in both empathy and erudition. Klay is well-read, and well-considered.

Klay writes of war, of suffering, of veterans, of aspirations and delusions and laments. His writing sends me to other books, as when he quotes G.K. Chesterton on the power of fairy tales: “They make rivers run with wine, only to make us remember, for one wild moment, that they run with water.” That line then sent me back to Orthodoxy, where I found another gem tucked in the same paragraph: “One may understand the cosmos, but never the ego; the self is more distant than any star.”

In the spirit of literary inversion, I’d like to turn Chesterton’s line back on Klay—his essays force citizens to consider their complacency, their imperception of the self, in the face of constant war. His work not just illuminating but challenging, in the way that all great essays force us to confront our inadequacies.

A veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps, Klay won the 2014 National Book Award for Fiction for his debut book, Redeployment. His novel, Missionaries, was named one of the ten best books of 2020 by the Wall Street Journal. His essays have appeared in the Atlantic, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and elsewhere, and he currently teaches fiction at Fairfield University.

A veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps, Klay won the 2014 National Book Award for Fiction for his debut book, Redeployment. His novel, Missionaries, was named one of the ten best books of 2020 by the Wall Street Journal. His essays have appeared in the Atlantic, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and elsewhere, and he currently teaches fiction at Fairfield University.

Nick Ripatrazone: In your introduction to Uncertain Ground, you note that many American citizens are “swaddled from the consequences” of war. I love the malleability of this metaphor: how we can often be made sheltered, silent, and infantile. In another essay, you write: “There’s something bizarre about being a veteran of a war that doesn’t end, in a country that doesn’t pay attention.” These essays were written over a period spanning at least a decade. What’s your sense of American awareness of war now?

Phil Klay: We’ve been excused from thinking about war by our political leaders. Congress doesn’t vote on wars anymore, journalists aren’t allowed to embed with troops, and when something happens like President Biden announcing he’s sending troops into Somalia, it isn’t done publicly but rather first leaked anonymously to the press, with scant details about why and what they’ll be doing. Also, right now we heavily rely on special operations troops, on drones and airstrikes and mercenaries and partnering with local forces to achieve our objectives. It’s a style of warfare designed to be opaque to the average civilian. And so there isn’t really much interest in how we are using military force around the world, even though it is obviously one of the most important and morally fraught exercises of American power.

NR: “Marines,” you write, “are drawn like moths to a flame when it comes to the dangerous, the transgressive, and the darkly humorous.” Do you think this translates to a literary or storytelling style for Marines as well—including yourself?

PK: Ha! Guilty, probably. There’s an impish streak in me that I hope is healthy for a writer, an attraction to the bizarre, the out-of-place, the disturbing. One should poke beehives from time to time, so long as that’s not all you’re doing. Transgression does not justify itself, but needs to be earned. By that I mean that simply showing the grotesque and cruel and darkly funny things that happen in war is not enough. One must have a moral vision, a sense of why and in what context you are showing these things such that the reader does not lose sight of the human beings in the midst of the spectacle of cruelty and absurdity.

I actually think that humor is one of the more powerful tools we have for this. People in war don’t just make jokes because it takes the edge off of horror. They make jokes because human extremes come out in all their startling immediacy in war, and humor is the most serious and honest response. Emerson, in his essay on the comedic, notes that:

There is no joke so true and deep in actual life as when some pure idealist goes up and down among the institutions of society, attended by a man who knows the world, and who, sympathizing with the philosopher’s scrutiny, sympathizes also with the confusion and indignation of the detected, skulking institutions. His perception of disparity, his eye wandering perpetually from the rule to the crooked, lying, thieving fact, makes the eyes run over with laughter.

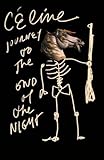

War is constant exposure to the difference between the rule and the crooked, lying, thieving fact, and the result is some of the funniest books ever written: Goodbye to All That, Journey to the End of the Night, The Good Soldier Schweik, Catch-22, Beer in the Snooker Club, and so on, right up to contemporary Iraqi literature like The Corpse Exhibition and Frankenstein in Baghdad.

War is constant exposure to the difference between the rule and the crooked, lying, thieving fact, and the result is some of the funniest books ever written: Goodbye to All That, Journey to the End of the Night, The Good Soldier Schweik, Catch-22, Beer in the Snooker Club, and so on, right up to contemporary Iraqi literature like The Corpse Exhibition and Frankenstein in Baghdad.

NR: At the end of one essay, you recall a Vietnam veteran telling the story of his best friend, who “was the sort of guy you could count on, even if he might not have been the best soldier in the world.” You add: “He was nineteen, and he always will be.” How does war affect our sense and conception of time—for veterans, especially?

PK: I think it affects veterans differently, and at different moments. I remember having beers with a veteran in Texas almost a decade ago. He showed me a grisly photo from Iraq of an injury he’d received in combat, a photo his young daughter had apparently found on his phone. It’d caused nightmares, and he’d had to talk her through what happened to him. He also had another, still younger child, and he said to me that right then was when he realized that he’d need, at some point, to have with them both “the sex talk, and the Iraq talk.” I suspect that his own relationship to what he’d been through, and his sense of that past event, suddenly warped as he saw it through the eyes of his child, and as he imagined retelling it in the future. I also think these current wars are particularly strange, in that they haven’t ended so much as become attenuated, and pushed to the side even while low-level military efforts continue.

NR: You briefly mention an essay “It’s Not That I’m Lazy” written by an anonymous veteran that appeared in the October 1, 1946 edition of Harper’s. I found and read the essay, and agree that it is as arresting as you describe. The veteran writes that his “respect for my civilian occupation was badly shaken. It wasn’t a rational change of mind. It was a gradual and unconscious effect of four years of membership in a military society which, if not contemptuous, was at least indifferent to my special abilities as a member of that other society back home.” Do you find contemporary veterans echoing a similar sentiment? Do you think that there are particular sectors of civilian society that are doing a good job of inviting veterans back into the civilian world?

PK: You know, I quote a veteran in the book who, during the fall of Kabul to the Taliban, said, “Everyone wants to know, am I OK, and I’m like, ‘Really?’ Is the burden of feeling guilty about this also a burden veterans have to carry, too? Not only did you not care about Afghanistan, not only did you not follow Afghanistan, it’s like you gave such a little shit you can’t even feel bad yourself? Could somebody else please take some of this, take some responsibility? I’m so fucking tired of it and it’s killing me and it shouldn’t be fucking me up this much.”

It was an expression of bitterness, and disconnect from the civilian world that had paid such little attention to the war that had been so formative for him. But I spoke to him a few months later, after he’d been doing work resettling Afghans, and he told me it’d been a revelation to him to see how many people had expressed an interest in helping. Many of these were people with no connection to the military or Afghanistan at all. “I used to think people were apathetic about Afghanistan and I don’t think that’s true,” he said. “I think it wasn’t communicated well. When everyday Americans see that there are people in need or there’s a crisis and people are lacking access to basic needs and treated in a way that denies them their basic human dignity, people have stepped up.”

One of the tragedies of these wars is that our political leaders have asked far less of our populace than they’re capable of. That said, there are absolutely places where that has happened. There are a lot of veterans in humanitarian communities working on immigration issues, with arts organizations, and so on. In some universities you’ll find that veterans can feel isolated, but others have taken pains to provide robust support to develop a real community. This often means a commitment of real resources. I’m currently at Fairfield University, which has committed funding to veterans who want to study in our MFA in creative writing program. Currently, about a third of the students are veterans, which has enabled an incredible community as well as the opportunity for real engagement between a diversity of veteran and civilian writers.

NR: You quote W. B. Yeats, who, while compiling poetry for The Oxford Book of Modern Verse, passed on English soldier-poets, saying “passive suffering is not a theme for poetry.” It’s certainly a glib statement from him, and it makes me think of your own appreciation for the talented work of David Jones, a Welsh soldier during World War I. Paul Sheehan finds an “oblique rejoinder to Yeats’s dictum” within In Parenthesis, where Jones writes of a soldier: “He found him all gone to pieces and not pulling himself together nor making the best of things. When they found him his friends came on him in the secluded fire-bay who miserably wept for the pity of it all and for the things shortly to come to pass and no hills to cover us.” As someone who mostly writes and publishes in prose, could you engage Yeats’s contention from a genre standpoint? Do you think fiction and nonfiction about war differs—in mode, intent, and perhaps result—from poetry about war?

NR: You quote W. B. Yeats, who, while compiling poetry for The Oxford Book of Modern Verse, passed on English soldier-poets, saying “passive suffering is not a theme for poetry.” It’s certainly a glib statement from him, and it makes me think of your own appreciation for the talented work of David Jones, a Welsh soldier during World War I. Paul Sheehan finds an “oblique rejoinder to Yeats’s dictum” within In Parenthesis, where Jones writes of a soldier: “He found him all gone to pieces and not pulling himself together nor making the best of things. When they found him his friends came on him in the secluded fire-bay who miserably wept for the pity of it all and for the things shortly to come to pass and no hills to cover us.” As someone who mostly writes and publishes in prose, could you engage Yeats’s contention from a genre standpoint? Do you think fiction and nonfiction about war differs—in mode, intent, and perhaps result—from poetry about war?

PK: What’s interesting is that although Yeats famously insulted Wilfred Owen as “a revered sandwich-board Man of the revolution… all blood, dirt & sucked sugar stick,” he greatly admired Jones (once, at a party where Jones was present, he entered and bowed low to salute the author of In Parenthesis). And of course, Jones’s work is far more than “passive suffering.” It’s complicated, because Yeats is not entirely wrong in his dissatisfaction with some of the trench poets when he suspects that they’re limiting themselves because they feel obliged to plead the suffering of their men. But he obviously misses the genuine power and beauty of Owen’s verse.

Owen, as a man who self-consciously crafted his poetry as a form of protest, and who died in the war, is a critical exemplar of the ‘poet as witness’, who, as Seamus Heaney put it, “represents poetry’s solidarity with the doomed, the deprived, the victimized, the under-privileged…[and for] whom the truth-telling urge and the compulsion to identify with the oppressed becomes necessarily integral with the act of writing itself.” And that’s a form I’ve distanced myself from.

As to whether fiction and nonfiction differ so much from poetry about war, I’m not sure. Poetry has been vital for me as a writer. Memorizing poetry to get the rhythms in my head. Working through the arguments and ideas and approaches to capturing experience in so many wars. I just read Tom Sleigh’s poetry collection The King’s Touch, which at points deals with his work as a journalist in conflict zones, and though obviously I work in prose Tom’s approach throughout his books has been pivotal for me as I think through what can be done with war writing, and how to balance ethical, political, and aesthetic commitments. Sleigh adopts a kind of caution about that in his work, a care that the poet not overstep his bounds, speak not simply for but over the voice of the oppressed, while nevertheless immersing the reader in the complexity of political fraught, emotionally intense and sometimes violent situations.

As to whether fiction and nonfiction differ so much from poetry about war, I’m not sure. Poetry has been vital for me as a writer. Memorizing poetry to get the rhythms in my head. Working through the arguments and ideas and approaches to capturing experience in so many wars. I just read Tom Sleigh’s poetry collection The King’s Touch, which at points deals with his work as a journalist in conflict zones, and though obviously I work in prose Tom’s approach throughout his books has been pivotal for me as I think through what can be done with war writing, and how to balance ethical, political, and aesthetic commitments. Sleigh adopts a kind of caution about that in his work, a care that the poet not overstep his bounds, speak not simply for but over the voice of the oppressed, while nevertheless immersing the reader in the complexity of political fraught, emotionally intense and sometimes violent situations.

I try to do the same—immerse the reader in situations of political, emotional, psychological or spiritual complexity, but without necessarily providing the reader with the clear emotional or political cashout we come to expect from some poetry of witness. As a war writer, you find that people are comfortable with clear jingoism or pure denunciation, and your job is not to provide comfort.

NR: The final section of the book is titled “Faith.” “Faith, for me, has always been a place to register a sense of doubt, of powerlessness, of inadequacy and uncertainty about my place in the world and how I am supposed to live,” you write. You note: “It increasingly seems to me that the certainty of earlier life was based on fantasies of an orderly future in a rational, controllable world, fantasies that were no more than the wish that the Leviathan might one day be tied down by force.” You write of times of doubt in your life, and your musings make me think of the differing conceptions of God between the Jesuit priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who imagined a unified cosmos and consciousness, and Fr. Raymond Nogar, who envisioned the difference between them as “His God is the Lord of order; my God is the Lord of the Absurd.” You seem inclined to agree with Nogar, but I wanted to see which vision of the divine is more in line with your Catholic sensibility—and what that means for you as a writer and a veteran.

PK: Oh wow, I apparently have another book I need to read! I do find Chardin fascinating. He was a veteran of World War I himself, and has some truly fascinating reflections on it. In one essay, written during the war, after he’d already served in several major battles, he reflected on the strange nostalgia that he felt whenever he was rotated out of the front. Why was it, though he hated pain and death and suffering as much as the next man, did he find himself wanting to return to the front, this cataclysmic site of death and destruction where he knew he could be killed at any moment, and where he would certainly encounter extreme suffering? And he goes through various explanations—that simple desire we have to encounter extremity and the unknown, the freedom from normal social convention, the sense of being submerged in a larger task, and the mystic encounter with the absolute he finds in such close exposure to horror. He writes:

No one, except those who have been there, will possess charged recollections of wonder that a man retains of the plain of Ypres in April of 1915, when the air of Flanders was filled with the smell of chlorine and when artillery shells cut down the poplar trees all along the Yperlé; or when the chalky slopes of souville in July of 1916 blossomed in death. These super-human hours impregnated life with a tenacious perfume, definitive in exaltation and initiation, as if one had passed through them into the absolute.

This compulsion we have toward horror is, I think, difficult for people to talk about, and yet it is most certainly there. It’s funny, every once in a while I’ll mention that the ostensibly anti-war film Full Metal Jacket has been a fantastically successful recruiting commercial for Marine Corps, and annoyed critics have informed me that this is because I’m stupid, or the viewers are stupid, since the correct interpretation is to be repulsed by what we see. But of course, human desires are more complex than that, something I appreciate in Chardin’s searching WWI work. But it’s precisely for that reason that I’m on Nogar’s side against Chardin here. Yes, I’m wary of the Lord of order. Far too often the order imagined by those who espouse such a god has far more to do with narrow human desires. For me it comes down to the strange, broken, beautiful, unruly creatures humans are, possessing of freedom and creativity which seems to explode outwards, rather than narrow to a point.