Even if you’ve never heard the name F. O. Matthiessen, you’ve felt his influence if you’ve read Walden, The House of Seven Gables, or Moby-Dick, or any number of American literary classics. As a Harvard professor from 1929 to 1950, Matthiessen helped solidify the stature of American writing at a time when “literature” often meant English literature. His most enduring legacy is as one of the founders of American Studies, an interdisciplinary field that draws from multiple areas of study, but especially history and literature.

Francis Otto Matthiessen was born February 2, 1902 in Pasadena, California. His father, Frederick William Matthiessen, Jr., was heir to the company fortune of Westclox, makers of the well-known Big Ben alarm clock. Matthiessen attended Yale College, graduating in 1923. Yale blossomed into a Rhodes Scholarship with two years at Oxford, followed by graduate study at Harvard, where he received his Ph.D. in 1927.

As a scholar and author, Matthiessen was especially attuned to writers who were as yet unknown or outside the boundaries of accepted literary tastes. His first book Sarah Orne Jewett was the first literary biography of the 19th century author, now considered a foundational figure in American literary regionalism. Some of his subjects were canonical insiders-in-the-making: At the time Matthiessen published his books, The Achievement of T.S Eliot: An Essay on the Nature of Poetry (1935) and Henry James: The Major Phase (1944), neither writer enjoyed the stature they do today.

American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman remains Matthiessen’s best-known work. Published in 1941, it surveys the writing of Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, Melville, and Whitman, who published many of their seminal works in the window of 1850 to 1855, in the run-up to the Civil War. The book contributed to the birth of American Studies and secured Matthiessen’s reputation as one of the leading critics of his day. But since the peak of Matthiessen’s popularity in the early-to-mid 20th century, literary scholarship and studies has largely moved on. Matthiessen’s understanding of canonical literature skewed white and male, whereas most critics and writers today debate the relevancy of a canon in the first place, much less who gets into it. Despite some of its outdated views, the book undeniably helped shape a new discipline—a rare feat, especially in the humanities—so Matthiessen has remained a force to contend with in scholarly debate, even if only to react against his ideas and literary judgments.

American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman remains Matthiessen’s best-known work. Published in 1941, it surveys the writing of Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, Melville, and Whitman, who published many of their seminal works in the window of 1850 to 1855, in the run-up to the Civil War. The book contributed to the birth of American Studies and secured Matthiessen’s reputation as one of the leading critics of his day. But since the peak of Matthiessen’s popularity in the early-to-mid 20th century, literary scholarship and studies has largely moved on. Matthiessen’s understanding of canonical literature skewed white and male, whereas most critics and writers today debate the relevancy of a canon in the first place, much less who gets into it. Despite some of its outdated views, the book undeniably helped shape a new discipline—a rare feat, especially in the humanities—so Matthiessen has remained a force to contend with in scholarly debate, even if only to react against his ideas and literary judgments.

Despite Matthiessen’s wealthy family and his privileged path to the ivory tower of academia, he was an ardent socialist activist and champion of economic equality. A great friend to organized labor, Matthiessen believed that civil and political freedom meant comparably little if not accompanied by economic opportunity and security. He helped found the Harvard Teachers’ Union, which tried to build bridges to other segments of the labor movement; vocally supported the 1948 Progressive Party presidential candidate, Henry Wallace; and was associated with at least eight groups deemed “subversive” by the U.S. Attorney General in the late 1940s.

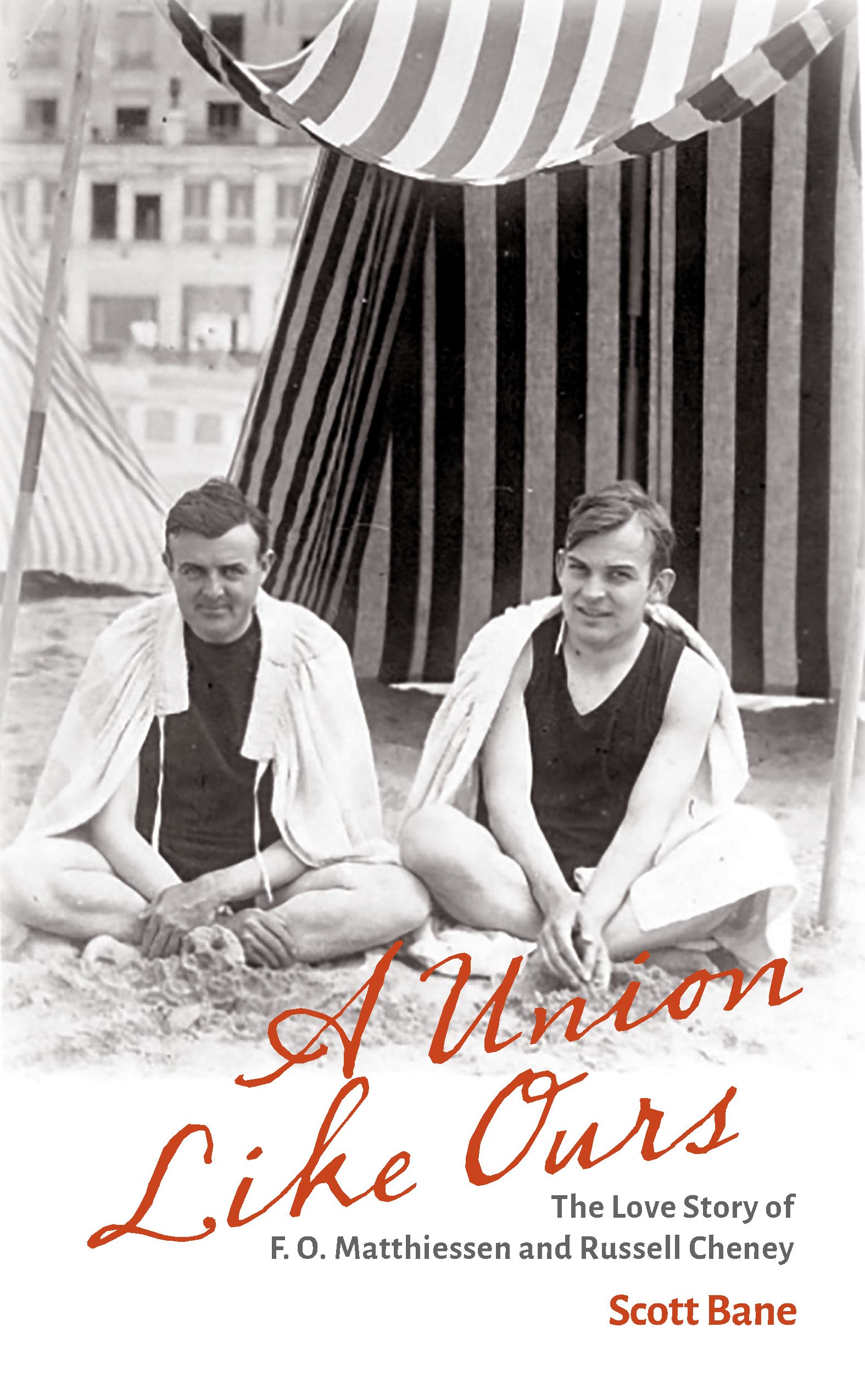

Matthiessen spoke out on just about any topic connected to progressive politics, except the one that touched his own life most directly: homosexuality. Matthiessen was a gay man involved in a relationship—effectively, in all but name and legal rights, a marriage—with the painter Russell Cheney. Matthiessen himself used the word “marriage” to describe their relationship: “Marriage! What a strange word to be applied to two men! Can’t you hear the hell-hounds of society baying full pursuit behind us?” Cheney was 20 years Matthiessen’s senior, but they had much in common: they both came from wealthy families, were educated at Yale, and were members of the college’s elite senior society, Skull and Bones. The two men met on the ocean liner Paris in 1924, and up until Cheney’s death in 1945, they remained a couple, establishing their home base in Kittery, Maine. Matthiessen had long struggled with depression, but it was compounded by unspeakable grief after Cheney died. On the night of March 31, 1950, Matthiessen checked himself into the Manger Hotel, which stood near North Station in Boston, and jumped from a twelfth story window.

Since Matthiessen’s death, there have been three scholarly books published about his legacy, as well as many articles examining everything from his criticism to his politics to his homosexuality. But surprisingly, Matthiessen has enjoyed a curious literary afterlife thanks to the work not of scholars but of novelists.

In 1952, just after Matthiessen’s death, Truman Nelson’s novel The Sin of the Prophet was published. Nelson was a self-educated, working-class writer, who made his living at the General Electric plant in Lynn, Massachusetts. Nelson had once heard Matthiessen speak at an organized labor meeting, and recalled his words that the person who meets “the ultimate challenge of life is the one who can be with the oppressed against the oppressor.” Afterward, Nelson wrote a letter to Matthiessen, and they started meeting regularly on Sundays, Nelson’s only day off. The Sin of the Prophet, which Nelson dedicated to Matthiessen, is a historical novel that opens a window into pre-Civil War Boston, dramatizing Unitarian minister Theodore Parker’s attempts to defy the Fugitive Slave Act and secure freedom for Anthony Burns, an escaped slave. Like Matthiessen, Nelson was indebted to 19th century American authors, especially Emerson, Thoreau, and Melville. Whereas Matthiessen read these authors to envision greater socioeconomic equality, Nelson read the same authors, along with Matthiessen’s analysis of their work, to agitate for greater racial equality.

In 1952, just after Matthiessen’s death, Truman Nelson’s novel The Sin of the Prophet was published. Nelson was a self-educated, working-class writer, who made his living at the General Electric plant in Lynn, Massachusetts. Nelson had once heard Matthiessen speak at an organized labor meeting, and recalled his words that the person who meets “the ultimate challenge of life is the one who can be with the oppressed against the oppressor.” Afterward, Nelson wrote a letter to Matthiessen, and they started meeting regularly on Sundays, Nelson’s only day off. The Sin of the Prophet, which Nelson dedicated to Matthiessen, is a historical novel that opens a window into pre-Civil War Boston, dramatizing Unitarian minister Theodore Parker’s attempts to defy the Fugitive Slave Act and secure freedom for Anthony Burns, an escaped slave. Like Matthiessen, Nelson was indebted to 19th century American authors, especially Emerson, Thoreau, and Melville. Whereas Matthiessen read these authors to envision greater socioeconomic equality, Nelson read the same authors, along with Matthiessen’s analysis of their work, to agitate for greater racial equality.

The Sin of the Prophet was followed by May Sarton’s 1955 novel Faithful Are the Wounds, an uneven book that tells the story of Harvard Professor Edward Cavan, who dies by suicide, purportedly over his failed progressive political activism. Sarton makes ample use of the facts of Matthiessen’s life, such as his support for Henry Wallace’s Presidential campaign and the legal battle over Matthiessen’s bequests to “subversive” organizations. But Sarton never captures in a believable way Cavan’s motivation for taking his own life: a parallel storyline to Matthiessen’s heartbreak over the loss of Cheney, the most important relationship of his adult life, is absent from the novel. Sarton, herself a lesbian who settled in York, Maine, not far from where Matthiessen and Cheney made their home, drops beads about Cavan’s homosexuality, describing him as “not the marrying kind,” but goes no further. This was not an unreasonable calculation to make. In the mid-1950s, Sarton could not write about an openly gay character, at least if she wanted to see her book in print by a national mainstream publisher.

The Sin of the Prophet was followed by May Sarton’s 1955 novel Faithful Are the Wounds, an uneven book that tells the story of Harvard Professor Edward Cavan, who dies by suicide, purportedly over his failed progressive political activism. Sarton makes ample use of the facts of Matthiessen’s life, such as his support for Henry Wallace’s Presidential campaign and the legal battle over Matthiessen’s bequests to “subversive” organizations. But Sarton never captures in a believable way Cavan’s motivation for taking his own life: a parallel storyline to Matthiessen’s heartbreak over the loss of Cheney, the most important relationship of his adult life, is absent from the novel. Sarton, herself a lesbian who settled in York, Maine, not far from where Matthiessen and Cheney made their home, drops beads about Cavan’s homosexuality, describing him as “not the marrying kind,” but goes no further. This was not an unreasonable calculation to make. In the mid-1950s, Sarton could not write about an openly gay character, at least if she wanted to see her book in print by a national mainstream publisher.

Perhaps the most richly imagined novel inspired by Matthiessen came from Mark Merlis in 1994. Merlis worked principally as a health policy analyst in philanthropy and government, but he also wrote four well-received novels. His first, American Studies, toggles back and forth between the present story of Reeve, a former student of the Matthiessen-like character Tom Slater, and Slater’s past story of sexual entanglement with a male student, his entrapment by Harvard, and his ultimate suicide. Merlis’s book embroiders the facts of Matthiessen’s story more than Sarton did: Slater dies by putting a gun in his mouth, rather than jumping from a hotel window. Nor was Matthiessen ever accused of or suspected of molesting any of his students. But Merlis captured and expressed the practical and emotional uncertainties that LGBTQ people experienced in pre-Stonewall America.

Perhaps the most richly imagined novel inspired by Matthiessen came from Mark Merlis in 1994. Merlis worked principally as a health policy analyst in philanthropy and government, but he also wrote four well-received novels. His first, American Studies, toggles back and forth between the present story of Reeve, a former student of the Matthiessen-like character Tom Slater, and Slater’s past story of sexual entanglement with a male student, his entrapment by Harvard, and his ultimate suicide. Merlis’s book embroiders the facts of Matthiessen’s story more than Sarton did: Slater dies by putting a gun in his mouth, rather than jumping from a hotel window. Nor was Matthiessen ever accused of or suspected of molesting any of his students. But Merlis captured and expressed the practical and emotional uncertainties that LGBTQ people experienced in pre-Stonewall America.

Louis Hyde, Matthiessen’s Skull and Bones brother from Yale, also contributed to the scholar’s curious literary afterlife by editing a collection of Matthiessen and Cheney’s love letters, Rat & the Devil: Journal Letters of F.O. Matthiessen and Russell Cheney, in 1978. (“Rat” and “Devil” were Cheney and Matthiessen’s respective Skull and Bones nicknames.) On his death, Matthiessen left his house in Kittery to Hyde, as well as roughly 3,100 letters that he and Cheney had exchanged in their lifetimes. A heterosexual investment manager, Hyde was an unlikely editor of a collection of gay love letters. Yet something about Matthiessen and Cheney’s love story captured Hyde’s imagination.

Matthiessen’s homosexuality often made him feel like an outsider, or at least an outsider trapped in an insider’s body and life, so he was frequently sensitive to the role of outsiders in capturing truths about life in America. It may seem surprising that a gay, politically progressive, socialist opponent of economic inequality should be such an astute interpreter of American life and in America and its native literature. But then again writers like Matthiessen are often the ones who most clearly see the divergence between America’s professed ideals and its reality, and who identify those aspects of America society that the self-appointed “defenders” are usually unwilling to acknowledge. As he wrote in the early 1930s: “Our most powerful individuals have again and again been dangerously isolated from or opposed to society as a whole.” Matthiessen recognized the power of this perspective, and Nelson, Sarton, Merlis, and Hyde have in turn recognized Matthiessen’s work and life as expressing something essential about American life, too.