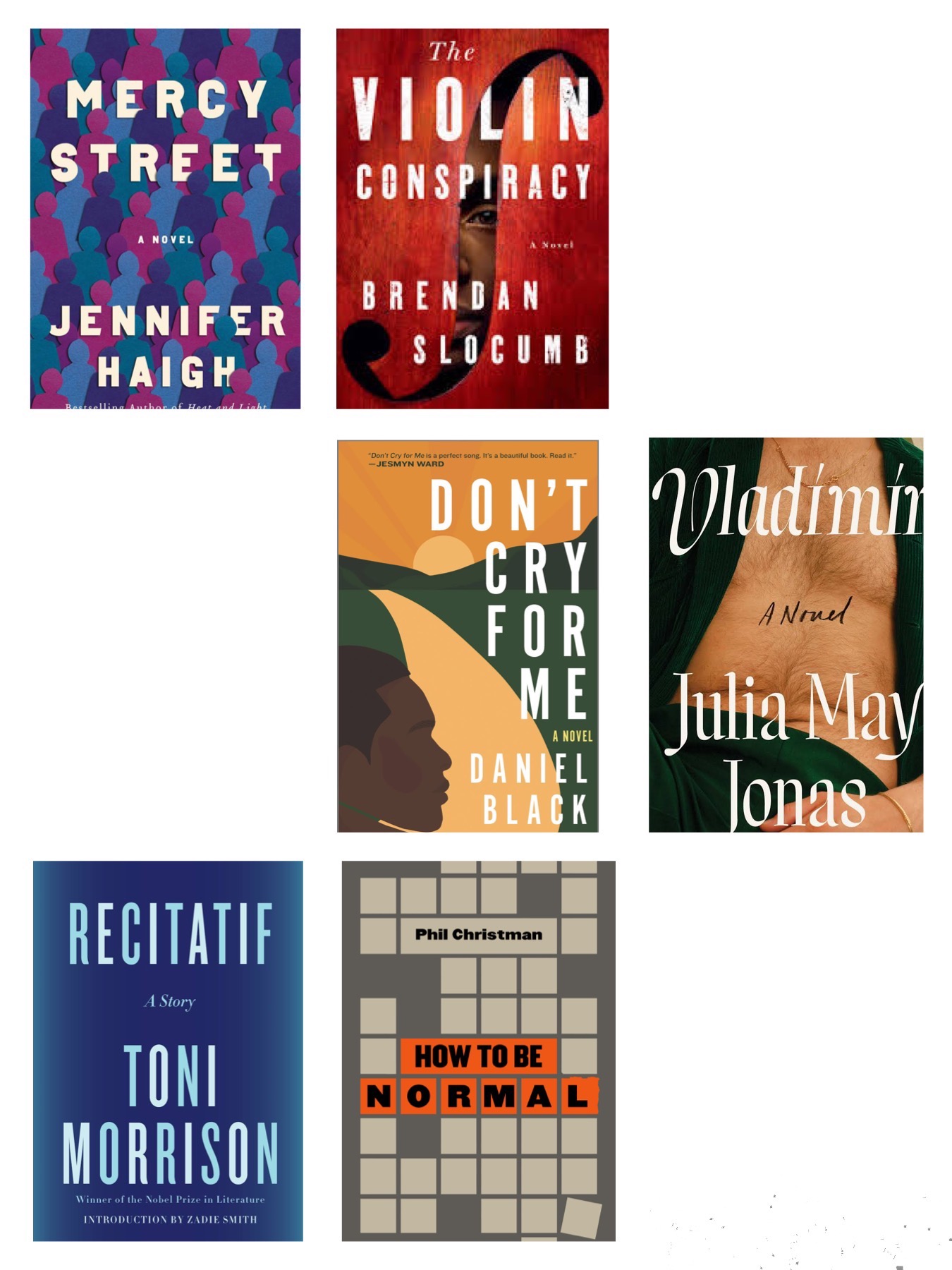

Here’s a quick look at some notable books—new titles from Daniel Black, Jennifer Haigh, and more—that are publishing this week.

Want to learn more about upcoming titles? Then go read our most recent book preview. Want to help The Millions keep churning out great books coverage? Then become a member today.

Recitatif by Toni Morrison

Recitatif by Toni Morrison

Here’s what Publishers Weekly had to say about Recitatif: “Originally published in 1983, this stunning work from Nobel laureate Morrison (God Help the Child) follows two women who share a tenuous bond after meeting at an orphanage at eight in the 1950s. As Zadie Smith notes in an illuminating introduction, Morrison (1931–2019) chose not to reveal the race of either character, just that one is Black and one is white. Twyla and Roberta connect over a shared sense of rejection after their single mothers were unable to take care of them. Morrison then jumps forward to the late ’60s with Twyla as a young woman working at a Howard Johnson’s near Kingston, N.Y., where Roberta comes in with a musician boyfriend who supposedly has an ‘appointment’ with Jimi Hendrix. During their awkward exchange, she mocks Twyla for not knowing who Hendrix is. Twelve years later, Twyla is married and living in segregated Newburgh, where she again sees Roberta while shopping at an upscale grocery store. Roberta now lives across the river in fancy Annandale, and she insists Twyla join her for coffee, then brings up a violent incident from the orphanage. Eventually, she accuses Twyla of committing an act of racial violence. The author’s experiment pays off brilliantly, forcing the reader to consider racial stereotypes while also providing an indelible story. The gravitas and unparalleled skill found in Morrison’s best-known work is on full display in this compact powerhouse.”

Don’t Cry for Me by Daniel Black

Don’t Cry for Me by Daniel Black

Here’s what Publishers Weekly had to say about Don’t Cry for Me: “Black (The Sacred Place) chronicles a father’s confession of his failures in this heartbreaking narrative. Jacob Swinton writes to his estranged gay son, Isaac, in an effort to, in Jacob’s words, provide a ‘record of a poor Black father’s appeal… what any dying daddy might say to his son.’ Jacob recounts his years growing up in Arkansas, where he bullied a queer classmate, and describes his courtship with his wife, Rachel, and their move to Kansas City, where they had Isaac. He also offers insight on Black history and the power of reading, and writes eloquently about the country versus the city, but the core is about how Jacob treats Isaac—having asked him, for instance, ‘Do you wanna be a sissy, boy?’ at the breakfast table after deriding his son for resisting sports, kissing a doll, and performing in a school play. Jacob’s shame is made palpable in his alternately hurtful and supportive correspondence (‘I wonder how to fix you’; ‘You weren’t the son I wanted’; ‘Be the kind of man you are, but be a man’), and the wisdom he gains along the way brings him to concluding remarks that are poignant and moving. The painful narrative of regret can feel preachy at times, but it is consistently powerful.”

Vladimir by Julia May Jonas

Vladimir by Julia May Jonas

Here’s what Publishers Weekly had to say about Vladimir: “Playwright Jonas debuts with a mordantly funny post-#MeToo campus story about a 50-something woman unhinged by desire for a younger man. The unnamed narrator, a tenured English professor at a small upstate New York liberal arts college, starts the fall semester embroiled in scandal. The scandal is not hers (at least not at first)—her husband, John, also a professor in the department, has been placed on leave pending the results of a hearing after being accused of sexual predation by a host of young women, many of them former students. Denounced by both her colleagues and her adult daughter for her complicity in John’s behavior, the narrator retreats into obsessive sexual fantasies about a new young colleague, Vladimir. She also yearns to recapture the physical allure of her youth and revive her own stagnant writing, and by the end, her behavior turns monstrous. Vain, narcissistic, and seemingly oblivious to the absurdity of her actions, the narrator can nevertheless pluck at readers’ sympathies, especially in the generous and thoughtful ways she helps her daughter during her own personal crisis. The author generously studs the narrative with clever literary allusions (the narrator describes her mind in contrast to Edna St. Vincent Millay’s: ‘more like a chaotic battle scene than the unfurling of insight’), and surprisingly upends assumptions about gender, power, and shame. Jonas is off to a strong start.”

The Violin Conspiracy by Brendan Slocumb

The Violin Conspiracy by Brendan Slocumb

Here’s what Publishers Weekly had to say about The Violin Conspiracy: “Black violinist Ray McMillian, the hero of Slocumb’s gripping debut, receives a $5 million ransom demand for his Stradivarius violin after the instrument is stolen from his New York City hotel room a few weeks before he’s due to perform in the prestigious Tchaikovsky Competition. When the police, the FBI, and the insurance company’s investigator hit dead ends, the case comes to a standstill. Flashback to Ray’s high school years in Charlotte, N.C., where he must deal with pervasive racism—and his mother nagging him to drop out and get a job. Meanwhile, his grandmother, who supports his musical aspirations, gives him her grandfather’s violin. At college, where he receives a full scholarship, Ray endures prejudice from fellow students, and a luthier repairing the heirloom discovers it’s a Stradivarius. This revelation leads members of the Marks clan, whose ancestors enslaved Ray’s ancestors, to claim the violin belongs to them. Legal battles over the violin’s ownership ensue. The tension builds as the competition looms, and Ray struggles to shake off doubts, not get caught in false leads, and focus on finding the missing violin. Slocumb sensitively portrays Ray’s resilience in the face of extreme racism. The author is off to a promising start.”

How to Be Normal by Phil Christman

How to Be Normal by Phil Christman

Here’s what Publishers Weekly had to say about How to Be Normal: “Critic and lecturer Christman (Midwest Futures) examines in these searching essays his various identities—as white, heterosexual, and a ‘left-of-center Christian,’ to name a few—through the lens of their being unexceptional. Despite what the title suggests, this isn’t a how-to, but rather an exploration of averageness in which Christman considers such subjects as racism, masculinity, artistry and religion. In ‘How to Be White,’ he surveys the ‘vast, flimsy’ nature of ‘whiteness’ and lambasts ‘shit-eating allyism,’ in which ‘a person of privilege suspends, at least rhetorically—most of the time it is only rhetorical—their… claim to basic self-respect or human rights.’ He critiques the prevalent usage of vague terms to assign value to art in ‘How to Be Cultured (II): Middlebrow,’ observing how in America, ‘None of us can enjoy our pleasures till we think someone wants us not to have them.’ Christman is at his sharpest when analyzing religion, as seen in ‘How to Be Religious (II): Fundamentalism,’ in which he reflects, ‘What growing up fundamentalist helped me learn early on, is how terribly wrong you can be while thinking very hard.’ While there are moments in which Christman doesn’t sufficiently articulate his line of thinking, his style is, for the most part, cogent and on-point. It’s a probing and provocative collection.”

Mercy Street by Jennifer Haigh

Mercy Street by Jennifer Haigh

Here’s what Publishers Weekly had to say about Mercy Street: “Haigh (Heat & Light) explores the issue of abortion in this layered if frustrating story of a Boston women’s health clinic. Claudia, a counselor at Mercy Street, struggles with insomnia and anxiety after the death of her difficult mother, as well as because of her daily work with women who are faced with unwanted pregnancies. To cope, she smokes weed. Meanwhile, antiabortion protesters mount a steady campaign outside the clinic, and Haigh delves into their world. Among them is a rabidly antiabortion activist and racist retiree named Victor, who is tangentially connected to Claudia’s dealer and maintains a website where he shames white women who visit Mercy Street. The set up is strong and culminates in Victor deciding to travel to Boston from his log cabin in Pennsylvania to ‘save’ Claudia, but the narrative runs out of steam just as it gets going. Haigh doesn’t successfully weave the different narrative threads, delving into what leads men to become violent antichoice activists, for instance, but leaving the female characters disappointingly unexplored. There are some solid building blocks, but they crumble into an unsatisfying resolution. This doesn’t hit the high marks it aims for.”