Two mysteries dominate discussions of Edgar Allan Poe, whose tales of revenge and murder still captivate us. First, there are the strange circumstances of his death in October of 1849. Then there’s the even stranger matter of his marriage to his much younger cousin, Virginia. What was the nature of their relationship? Was it sexual, and if so, why didn’t they have children?

“I was a child and she was a child,” Poe wrote in “Annabel Lee,” his late-life poem seemingly inspired by his marriage. In fact, Poe was 27 when, in May of 1836, he wed Virginia Clemm in a boarding-house parlor. She was not quite 14, an exceptionally young bride even by the standards of their day. As offensive as the marriage may be to modern mores, it appears to have been motivated by Poe’s understandable desire to unite what little family he had, while his aunt, Maria Clemm—Virginia’s mother—consented to the union, and always lived with the couple afterward.

The Poes would be married for 11 years, but whether the marriage was consummated, immediately or later, has bedeviled scholars for over a century. In the 1920s, Joseph Wood Krutch theorized that Poe was “psychically” and physically impotent. A decade later, Marie Bonaparte, also applying psychoanalytic concepts to Poe’s life and work, alleged that Poe never acted on any of his sexual desires, with Virginia or anyone else, because his true interests lay in “sado-necrophilia.” Nor has such thinking fallen altogether out of fashion. In 2000, Jan Finkel cited Krutch’s impotence theory, saying, “there is no evidence that Poe ever had an adult relationship with a woman.”

Children are the usual proof we get of anyone’s sexual relationship, so the Poes’ lack thereof has fueled this salacious speculation. Yet other evidence does exist—and can’t be ignored. In Poe’s 1842 story “Eleonora,” for example, a pair of cousins grow up together in a beautiful valley, until the female cousin turns 15. At that time, “locked in each other’s embrace,” the two at last discover “Eros,” or love and desire. In turn, the valley blooms, ringing with life like a Wagner opera. Even the clouds of the sky grow closer to the ground, Poe writes, “shutting us up, as if forever, within a magic prison-house of grandeur and of glory.”

His gift for metaphor shines here. Comparing erotic life to a “magic prison-house” is a dead-on analogy to make you laugh in the painful way. The whole passage is Poe at his most explicit and seemingly autobiographical, appearing to imply that he and Virginia did know sexual joy, and to imply further that this aspect of their relationship began closer to Virginia’s 15th birthday, or approximately 16 months after the wedding, in late 1837. Poe often fudged dates, it’s true, sometimes shaving a few years off his own age to portray himself as more of a Romantic wunderkind, and adding a year or two to Virginia’s age when it suited him, too. But here again the explicitness of the passage, and the specificity of the timeline given as a relationship between cousins blossoms into mutual desire, is hard to ignore.

What’s more, the Poes’ friends described the marriage as intimate, with George Graham, Poe’s one-time boss and one of the most reliable firsthand sources, characterizing Poe as a “devoted husband.” Likewise, there is Virginia’s only known poem, a sweet acrostic written as a Valentine’s Day present, in which she tells her husband, “Ever with thee I wish to roam/Dearest, my life is thine.” The overall suggestion is one of profound love as well as intense domestic devotion.

Finally, there are the simple odds to consider. Not all marriages are physically consummated, not then and not now; the majority are, making it more likely than not that the Poes eventually developed a sexual relationship. By the same token, more people were (and are) fertile than not. We are indeed assuming a lot if we say that the Poes were likely sexually active as well as fertile, and I admit I’m speculating here, just the same as earlier commentators. Still, after five years’ deep research into Poe, consummated in a book, I’m convinced I’ve arrived at the real reason they had no children. It’s a hidden-in-plain-sight answer that readers today, amidst the rising costs of childcare and medical care, may grasp straightaway: The Poes simply couldn’t afford to have kids.

Here again, the timeline emerges as compelling. Line up the years and you will spot the economic rationale: The Poes’ marriage in fact took shape during the most devastating financial crisis in American history, at least until the Great Depression a century later. They married in the late spring of 1836. Within a year, the Panic of 1837 was fully underway, with banks shuttering and asset prices collapsing. Tens of thousands of people lost their livelihoods.

The Poes were affected, too, all the more so because Poe had chosen almost the exact moment before the crisis hit to try and trade up. In the early months of 1837, he’d left (or perhaps was fired from) his job at the Southern Literary Messenger. The Panic hit soon after, and the better job Poe had hoped to pursue in New York seems to have evaporated, essentially overnight. He could hardly any find freelance work, either. The effects of the crisis lingered for years, and his income during its depths averaged just $4 a day, adjusted for inflation. At times, the family had nothing to eat but bread and molasses.

If, as Poe hinted in “Eleonora,” he and Virginia consummated the marriage in late 1837, it would’ve been an impoverished moment, not the time to consider adding to a family. This is where birth control might have entered the Poes’ picture, and where their larger era’s massive drop in birth rates becomes relevant. In fact, birth rates declined so dramatically throughout the 19thh century that historians who track such arcane matters call it the “demographic transition.” Between 1800 and 1900, white married couples went from having an average seven children to fewer than four. The rate of extramarital pregnancy similarly plummeted during Poe’s lifetime.

Historians debate the causes of this shift, ascribing it to urbanization, war, and toward the end of the century, the beginnings of the women’s movement. So far, so plausible, but birth control’s role must be acknowledged. Techniques known in the Poes’ day included coitus interruptus, condoms, douching, and abortifacients (or pills to induce miscarriage that were advertised in a coded, if not coy, manner). Abortion was a relatively common practice, too, and broadly legal. My admittedly prurient best guess is that the Poes may have practiced one or more of these methods, with the lowest-cost methods the most likely.

And by the time their fortunes were looking up in the early 1840s? Virginia had grown ill with tuberculosis, which can cause infertility, while there are the secondary effects of grave illness to consider as well. The couple may have believed Virginia’s health too weak to risk a pregnancy after 1842, when she began to show symptoms. And in fact, Virginia would die in early 1847, closing the question forever.

In the end, there’s no way to prove this theory that the Poes didn’t have children because they couldn’t afford it. Perhaps factors in their diet and environment or some epigenetic cause made birth control unnecessary. Maybe I myself am the flaw in the rationale, inevitably seeing the history through the lens of my own millennial experience because I live in an era when economic crises and the rising cost of raising children have caused many people to delay or even forego parenthood. But my hunch, honed by research, is that a lot less has changed since the Poes’ time than we might hope. Rather, our own day is, to borrow a thought from the great Romantic biographer Richard Holmes, a “particularly fruitful moment” to rethink Poe—a moment in which his life story can take on a new “particular and poignant resonance.”

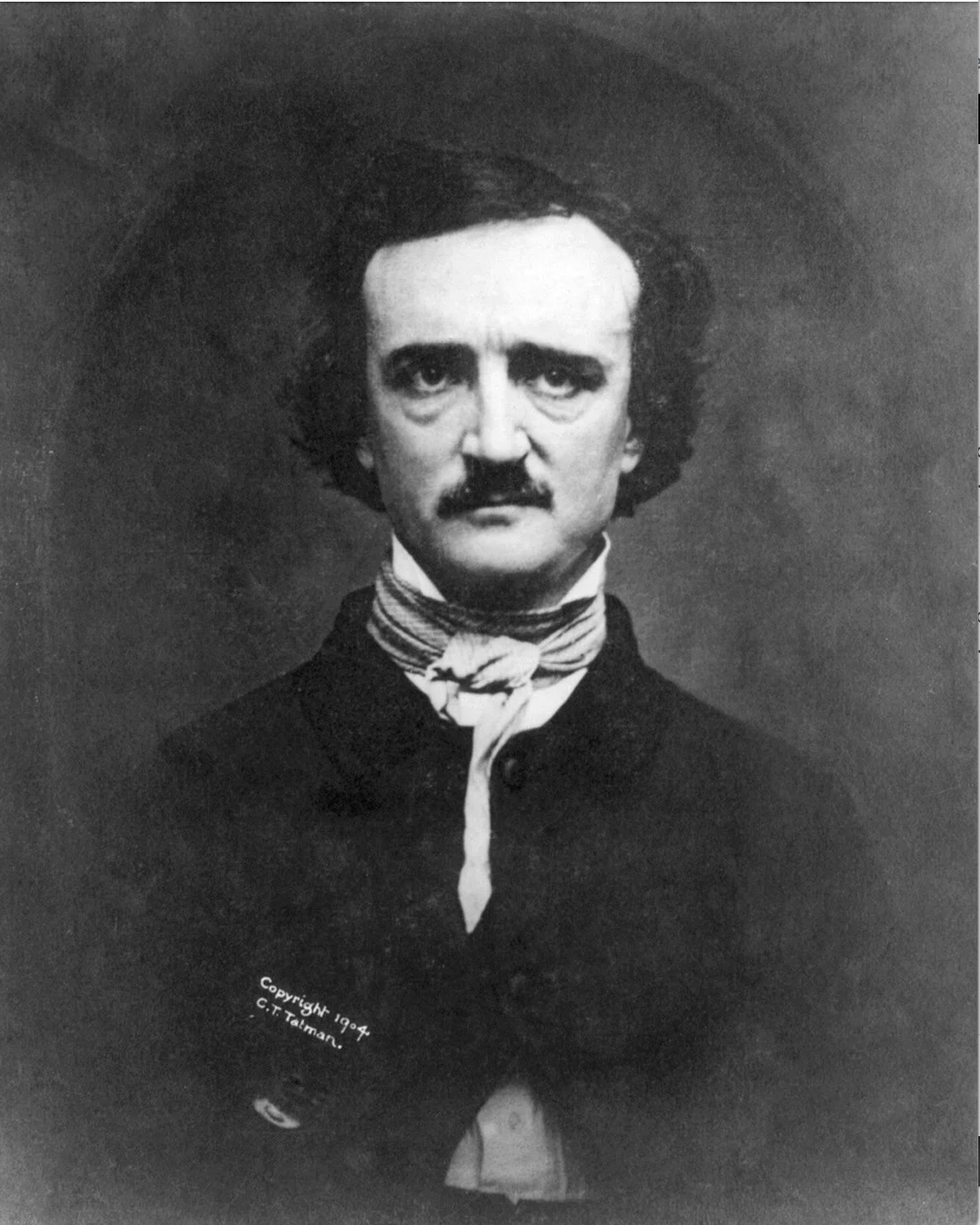

Image Credit: Pixabay