At its best, my reading is about connection: with people, with ideas and other books, which, when chased down, inevitably means forgetting a lot of which I’ve read. Beyond a document of sentences that astonish me, I don’t keep a list or a reading journal (much of this was written referring to my list of books previously checked out from the library). A recap of what I’ve read in a year felt almost impossible at first—how to write about such a diverse array of books and connect them to one another? But after sitting with this for awhile, I think I’ve grasped the thread: these days, I gravitate toward writers who have a “project,” who are concerned with—and consumed by—the search for something, unraveling a knot of ideas, or otherwise interested in producing works that accumulate over years and move toward…something.

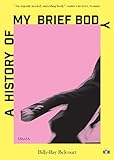

I like this because it embraces failure—each book is an admission that the last one didn’t quite capture what the author was trying to say, and so another is needed. I recognize this feeling; it’s the one that keeps me writing. It might be Billy-Ray Belcourt’s decolonial faggotry in A History of My Brief Body, or Rajiv Mohabir’s quick flourishing this year in memoir (Antiman) and poetry (Cutlish), all of which is linked together by his musicality and study of Bhojpuri Guyanese folk songs. Reading everything in a writer’s oeuvre often isn’t necessary to recognize a project, and it can be pleasurable to dip into the stream of one person’s life’s work, bathing in their observances, their obsessions so different from my own.

I like this because it embraces failure—each book is an admission that the last one didn’t quite capture what the author was trying to say, and so another is needed. I recognize this feeling; it’s the one that keeps me writing. It might be Billy-Ray Belcourt’s decolonial faggotry in A History of My Brief Body, or Rajiv Mohabir’s quick flourishing this year in memoir (Antiman) and poetry (Cutlish), all of which is linked together by his musicality and study of Bhojpuri Guyanese folk songs. Reading everything in a writer’s oeuvre often isn’t necessary to recognize a project, and it can be pleasurable to dip into the stream of one person’s life’s work, bathing in their observances, their obsessions so different from my own.

Other notable projects: The White Book by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith, a tour of white objects and fables through which a story of grief emerges. The book I spent the longest time reading this year: Sir Francis Bacon’s Novum Organum, first published in Latin in 1620, bewitched me with the simplest of sentences about water, air, and heat. Li Juan’s Winter Pasture: One Woman’s Journey with China’s Kazakh Herders was an impulse pickup in the library one day when I walked by the shelf, and preserves in the translation by Jack Hargreaves and Yan Yan much of Juan’s humor in living with a nomadic family, building shelter out of dung, and a way of life fast disappearing. Minor Detail by Adania Shibli, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette, a book so chillingly violent and obfuscating in its bifurcated narrative about the Israeli occupation of Palestine that it shook me to my core.

Other notable projects: The White Book by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith, a tour of white objects and fables through which a story of grief emerges. The book I spent the longest time reading this year: Sir Francis Bacon’s Novum Organum, first published in Latin in 1620, bewitched me with the simplest of sentences about water, air, and heat. Li Juan’s Winter Pasture: One Woman’s Journey with China’s Kazakh Herders was an impulse pickup in the library one day when I walked by the shelf, and preserves in the translation by Jack Hargreaves and Yan Yan much of Juan’s humor in living with a nomadic family, building shelter out of dung, and a way of life fast disappearing. Minor Detail by Adania Shibli, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette, a book so chillingly violent and obfuscating in its bifurcated narrative about the Israeli occupation of Palestine that it shook me to my core.

Then, over the summer, Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry finally arrived from the library, although I’ve since purchased it. I couldn’t imagine living without constant access to the poems and descriptive essays within, a few of which I knew, but many of which I didn’t, like Ed Roberson, whose collection To See the Earth Before the End of the World I sought out at Open Poetry Books in Seattle one weekend. Roberson is yet another with a project, one that unravels a unique way of looking at the world closely and methodically.

Then, over the summer, Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry finally arrived from the library, although I’ve since purchased it. I couldn’t imagine living without constant access to the poems and descriptive essays within, a few of which I knew, but many of which I didn’t, like Ed Roberson, whose collection To See the Earth Before the End of the World I sought out at Open Poetry Books in Seattle one weekend. Roberson is yet another with a project, one that unravels a unique way of looking at the world closely and methodically.

Black Nature was responsible for a spawning of sorts in the second half of my reading year. Through its pages I found C.S. Giscombe and his wonderful anti-travel book Into and Out of Dislocation. In this memoir (of sorts) he attempts to trace the almost untraceable path of another Black Giscombe from Jamaica in the remote wilderness of British Columbia in the 19th century, and in the process he traverses many of the places where I’ve lived or spent time, from remote upstate New York to New Hampshire to Seattle, most of it by bike, all set to meditations on what it means to travel through very white Canada and the Great North as a Black man in a poet’s voice. His project frustrates him, and he writes beguilingly about the dead ends he’s faced with again and again, which, of course, makes them not really “dead” at all but full of meaning.

Black Nature was responsible for a spawning of sorts in the second half of my reading year. Through its pages I found C.S. Giscombe and his wonderful anti-travel book Into and Out of Dislocation. In this memoir (of sorts) he attempts to trace the almost untraceable path of another Black Giscombe from Jamaica in the remote wilderness of British Columbia in the 19th century, and in the process he traverses many of the places where I’ve lived or spent time, from remote upstate New York to New Hampshire to Seattle, most of it by bike, all set to meditations on what it means to travel through very white Canada and the Great North as a Black man in a poet’s voice. His project frustrates him, and he writes beguilingly about the dead ends he’s faced with again and again, which, of course, makes them not really “dead” at all but full of meaning.

Black Nature also inspired me to revisit Dionne Brand’s work, something that’s been on my list since I barely scratched the surface in graduate school with In Another Place, Not Here. This time I worked my way through Bread Out of Stone and A Map to the Door of No Return, in which the door is that which her enslaved Black ancestors stepped through when they were kidnapped and forcibly removed from their homelands. Each time I read a book of Brand’s, I’m no closer to fully understanding her project—she does not write for my understanding, and that’s a liberating way to read, to not be catered to. I enjoy reading work that is not for me the most.

Black Nature also inspired me to revisit Dionne Brand’s work, something that’s been on my list since I barely scratched the surface in graduate school with In Another Place, Not Here. This time I worked my way through Bread Out of Stone and A Map to the Door of No Return, in which the door is that which her enslaved Black ancestors stepped through when they were kidnapped and forcibly removed from their homelands. Each time I read a book of Brand’s, I’m no closer to fully understanding her project—she does not write for my understanding, and that’s a liberating way to read, to not be catered to. I enjoy reading work that is not for me the most.

There were books that stood out not for the larger projects they gesture toward, but for their ephemerality and singularity of voice. Neotenica by Joon Oluchi Lee is indescribable, by far the weirdest book I read this year, and the author whom I’m most eager to read more from in the future. Cooper Lee Bombardier’s memoir Pass with Care gave me a living mirror and made me cry. You Are Eating an Orange. You Are Naked. by Sheung-King took a whirlwind spin through story and romance in the city, that somehow felt older than time.

There were books that stood out not for the larger projects they gesture toward, but for their ephemerality and singularity of voice. Neotenica by Joon Oluchi Lee is indescribable, by far the weirdest book I read this year, and the author whom I’m most eager to read more from in the future. Cooper Lee Bombardier’s memoir Pass with Care gave me a living mirror and made me cry. You Are Eating an Orange. You Are Naked. by Sheung-King took a whirlwind spin through story and romance in the city, that somehow felt older than time.

Finally, I spent one (different) blustery fall weekend in Seattle reading a copy of Bill Carty’s Huge Cloudy from a friend’s shelf, and I was compelled to finish it before leaving to drive back to Portland. I reached out to Bill to tell him how much I liked the collection, and he generously sent me a copy, in which he inscribed the weather at the moment of signing. This, project or not, is what a book is to me: a portal to a distinct time and place, which might be last week or 400 years ago. I do a lot of bouncing around between these portals, and it can get disorienting, but I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Finally, I spent one (different) blustery fall weekend in Seattle reading a copy of Bill Carty’s Huge Cloudy from a friend’s shelf, and I was compelled to finish it before leaving to drive back to Portland. I reached out to Bill to tell him how much I liked the collection, and he generously sent me a copy, in which he inscribed the weather at the moment of signing. This, project or not, is what a book is to me: a portal to a distinct time and place, which might be last week or 400 years ago. I do a lot of bouncing around between these portals, and it can get disorienting, but I wouldn’t have it any other way.

More from A Year in Reading 2021 (opens in a new tab)

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005