Maybe during this broiling summer you’ve seen the footage—in one striking video, women and men stand dazed on a boat sailing away from the Greek island of Evia, watching as ochre flames consume their homes in the otherwise dark night. Similar hellish scenes are unfolding in Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, as well as in Turkey and Spain. Currently Siberia is experiencing the largest wildfire in recorded history, an unlikely place for such a conflagration, joined by large portions of Canada. As California burns, the global nature of our immolation is underscored by horrific news around the world, a demonstration of the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Report on Climate Change’s conclusion that such disasters are “unequivocally” anthropogenic, with the authors signaling a “code red” for the continuation of civilization. On Facebook, the mayor of a town in Calabria mourned that “We are losing our history, our identity is turning to ashes, our soul is burning,” and though he was writing specifically about the fires raging in southern Italy, it’s a diagnosis for a dying world as well.

Seven centuries ago, another Italian wrote in The Divine Comedy, “Abandon all hope ye who enter here,” which seems just as applicable in 2021 as it did in 1221. That exiled Florentine had similar visions of conflagration, describing how “Above that plain of sand, distended flakes/of fire showered down; their fall was slow –/as snow descends on alps when no wind blows… when fires fell, /intact and to the ground.” This September sees the 700th anniversary of both the completion of The Divine Comedy and the death of its author Dante Alighieri. But despite the chasms of history that separate us, his writing about how “the never-ending heat descended” holds a striking resonance. During our supposedly secular age, the singe of the inferno feels hotter when we’ve pushed our planet to the verge of apocalyptic collapse. Dante, you must understand, is ever applicable in our years of plague and despair, tyranny and treachery.

Seven centuries ago, another Italian wrote in The Divine Comedy, “Abandon all hope ye who enter here,” which seems just as applicable in 2021 as it did in 1221. That exiled Florentine had similar visions of conflagration, describing how “Above that plain of sand, distended flakes/of fire showered down; their fall was slow –/as snow descends on alps when no wind blows… when fires fell, /intact and to the ground.” This September sees the 700th anniversary of both the completion of The Divine Comedy and the death of its author Dante Alighieri. But despite the chasms of history that separate us, his writing about how “the never-ending heat descended” holds a striking resonance. During our supposedly secular age, the singe of the inferno feels hotter when we’ve pushed our planet to the verge of apocalyptic collapse. Dante, you must understand, is ever applicable in our years of plague and despair, tyranny and treachery.

People are familiar with The Divine Comedy’s tropes even if they’re unfamiliar with Dante. Because all of it—the flames and sulphur, the mutilations and the shrieks, the circles of the damned and the punishments fitted to the sin, the descent into subterranean perdition and the demonic cacophony—find their origin with him. Neither Reformation nor revolution has dispelled the noxious fumes from inferno. There must be a distinction between the triumphalist claim that Dante says something vital about the human condition, and the objective fact that in some ways Dante actually invented the human condition (or a version of it). When watching the videos of people escaping from Evia, it took me several minutes to understand what it was that I was looking at, and yet those nightmares have long existed in our culture, as Dante gave us a potent vocabulary to describe Hell centuries ago. For even to deny Hell is to deny something first completely imagined by a Medieval Florentine.

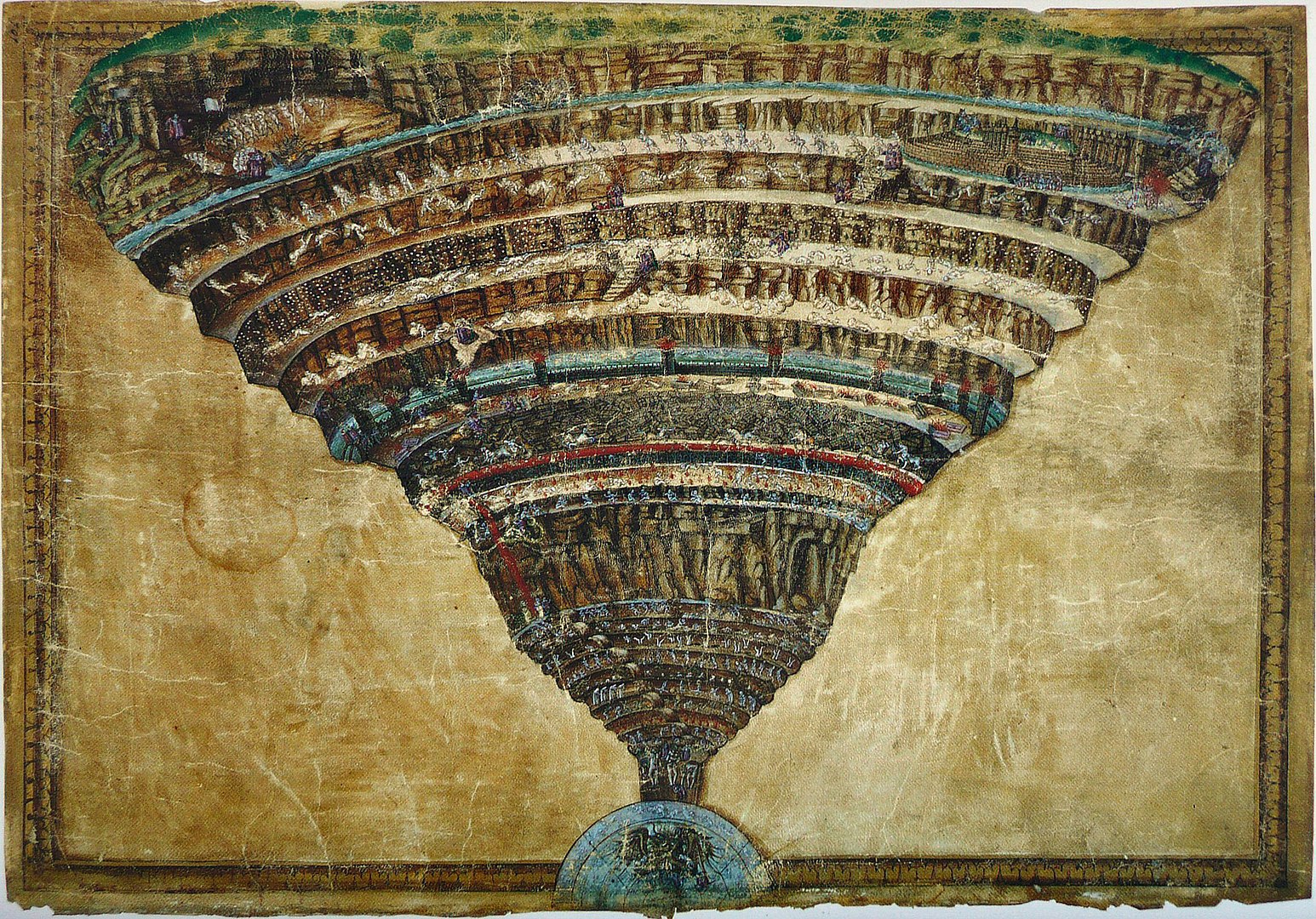

Son of a prominent family, enmeshed in conflicts between the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire, a respected though ultimately exiled citizen, Dante resided far from the shores of modernity, though the broad contours of his poem, with its visceral conjurations of the afterlife, are worth repeating. “Midway upon the journey of our life/I found myself within a forest dark,” Dante famously begins. At the age of 35, Dante descends into the underworld, guided by the ancient Roman poet Virgil and sustained by thoughts of his platonic love for the lady Beatrice. That Inferno constitutes only the first third of The Divine Comedy—subsequent sections consider Purgatory and Heaven—yet that it is the most read, speaks to something cursedly intrinsic in us. The poet descends like Orpheus, Ulysses, and Christ before him deep into the underworld, journeying through nine concentric circles, each more brutal than the previous. Perdition is a space of “sighs and lamentations and loud cries” filled with “Strange utterances, horrible pronouncements, /accents of anger, words of suffering, /and voice shrill and faint and beating hands” who are buffeted “forever through that turbid, timeless air, /like sand that eddies when a whirlwind swirls.” Cosmology is indistinguishable from ethics, so that each circle was dedicated to particular sins: the second circle is reserved for crimes of lust, the third to those of gluttony, the fourth to greed, the wrathful reside in the fifth circle, the sixth is domain of the heretics, the seventh is for the violent, all those guilty of fraud live in the eighth, and at the very bottom that first rebel Satan is eternally punished alongside all traitors.

Son of a prominent family, enmeshed in conflicts between the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire, a respected though ultimately exiled citizen, Dante resided far from the shores of modernity, though the broad contours of his poem, with its visceral conjurations of the afterlife, are worth repeating. “Midway upon the journey of our life/I found myself within a forest dark,” Dante famously begins. At the age of 35, Dante descends into the underworld, guided by the ancient Roman poet Virgil and sustained by thoughts of his platonic love for the lady Beatrice. That Inferno constitutes only the first third of The Divine Comedy—subsequent sections consider Purgatory and Heaven—yet that it is the most read, speaks to something cursedly intrinsic in us. The poet descends like Orpheus, Ulysses, and Christ before him deep into the underworld, journeying through nine concentric circles, each more brutal than the previous. Perdition is a space of “sighs and lamentations and loud cries” filled with “Strange utterances, horrible pronouncements, /accents of anger, words of suffering, /and voice shrill and faint and beating hands” who are buffeted “forever through that turbid, timeless air, /like sand that eddies when a whirlwind swirls.” Cosmology is indistinguishable from ethics, so that each circle was dedicated to particular sins: the second circle is reserved for crimes of lust, the third to those of gluttony, the fourth to greed, the wrathful reside in the fifth circle, the sixth is domain of the heretics, the seventh is for the violent, all those guilty of fraud live in the eighth, and at the very bottom that first rebel Satan is eternally punished alongside all traitors.

Though The Divine Comedy couldn’t help but reflect the concerns of Dante’s century, he still formulated a poetics of damnation so tangible and disturbing that it’s still the measure of hellishness, wherein he “saw one/Rent from the chin to where one breaks wind. /Between his legs were hanging down his entrails;/His heart was visible, and the dismal sack/That makes excrement of what is eaten.” Lest it be assumed that this is simply sadism, Dante is cognizant of how gluttony, envy, lust, wrath, sloth, covetousness, and pride could just as easily reserve him a space. Which is part of his genius; Dante doesn’t just describe Hell, which in its intensity provides an unparalleled expression of pain, but he also manifests a poetry of justice, where he’s willing to implicate himself (even while placing several of his own enemies within the circles of the damned).

No doubt the tortures meted out—being boiled alive for all eternity, forever swept up in a whirlwind, or masticated within the freezing mouth of Satan—are monstrous. The poet doesn’t disagree—often he expresses empathy for the condemned. But the disquiet that we and our fellow moderns might feel is in part born out of a broad theological movement that occurred over the centuries in how people thought about sin. During the Reformation, both Catholics and Protestants began to shift the model of what sin is away from the Seven Deadly Sins, and towards the more straightforward Ten Commandments. For sure there was nothing new about the Decalogue, and the Seven Deadly Sins haven’t exactly gone anywhere, but what took hold—even subconsciously—was a sense that sins could be reduced to a list of literal injunctions. Don’t commit adultery, don’t steal, don’t murder. Because we often think of sin as simply a matter of broken rules, the psychological acuity of Dante can be obscured. But the Seven Deadly Sins are rather more complicated—we all have to eat, but when does it become gluttony? We all have to rest, but when is that sloth?

An interpretative brilliance of the Seven Deadly Sins is that they explain how an excess of otherwise necessary human impulses can pervert us. Every human must eat; most desire physical love; we all need the regeneration of rest—but when we slide into gluttony, lust, sloth, and so on, it can feel as if we’re sliding into the slime that Dante describes. More than a crime, sin is a mental state which causes pain—both within the person who is guilty and to those who suffer because of those actions. In Dante’s portrayal of the stomach-dropping, queasy, nauseous, never-ending uncertainty of the damned’s lives, the poet conveys a bit of their inner predicament. The Divine Comedy isn’t some punitive manual, a puritan’s little book of punishments. Rather than a catalogue of what tortures match which crimes, Dante’s book expresses what sin feels like. Historian Jeffrey Burton Russell writes in Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages how in hell “we are weighted down by sin and stupidity… we sink downward and inward… narrowly confined and stuffy, our eyes gummed shut and our vision turned within ourselves, drawn down, heavy, closed off from reality, bound by ourselves to ourselves, shut in and shut off… angry, hating, and isolated.”

An interpretative brilliance of the Seven Deadly Sins is that they explain how an excess of otherwise necessary human impulses can pervert us. Every human must eat; most desire physical love; we all need the regeneration of rest—but when we slide into gluttony, lust, sloth, and so on, it can feel as if we’re sliding into the slime that Dante describes. More than a crime, sin is a mental state which causes pain—both within the person who is guilty and to those who suffer because of those actions. In Dante’s portrayal of the stomach-dropping, queasy, nauseous, never-ending uncertainty of the damned’s lives, the poet conveys a bit of their inner predicament. The Divine Comedy isn’t some punitive manual, a puritan’s little book of punishments. Rather than a catalogue of what tortures match which crimes, Dante’s book expresses what sin feels like. Historian Jeffrey Burton Russell writes in Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages how in hell “we are weighted down by sin and stupidity… we sink downward and inward… narrowly confined and stuffy, our eyes gummed shut and our vision turned within ourselves, drawn down, heavy, closed off from reality, bound by ourselves to ourselves, shut in and shut off… angry, hating, and isolated.”

If such pain were only experienced by the guilty, that would be one thing, but sin effects all within the human community who suffer as a result of pride, greed, wrath, and so on. There is a reason why the Seven Deadly Sins are what they are. In a world of finite resources, to valorize the self above all others is to take food from the mouths of the hungry, to hoard wealth that could be distributed to the needy, to claim vengeance as one’s own when it is properly the purview of society, to enjoy recreation upon the fruits of somebody else’s labor, to reduce another human being to a mere body, to covet more than you need, or to see yourself as primary and all others as expendable. Metaphor is the poem’s currency, and what’s more real than the intricacies of how organs are pulled from orifices is how sin—that disconnect between the divine and humanity—is experienced. You don’t need to believe in a literal hell—I don’t—to see what’s radical in Dante’s vision. What Inferno offers isn’t just grotesque descriptions, increasingly familiar though they may be on our warming planet, but also a model of thinking about responsibility to each other in a connected world.

Such is the feeling of the anonymous authors of the 2018 anarchist manifesto The Invisible Committee—a surprise hit when published in France—who opined that “No bonds are innocent” in our capitalist era, for “We are already situated within the collapse of a civilization,” structuring their tract around the circles of Dante’s inferno. Since its composition, The Divine Comedy has run like a molten vein through culture both rarefied and popular; from being considered by T.S. Eliot, Samuel Becket, Primo Levi, and Dereck Walcott, to being referenced in horror films, comic books, and rock music. Allusion is one thing, but what we can see with our eyes is another—as novelist Francine Prose writes in The Guardian, those images of people fleeing from Greek wildfires are “as if Dante filmed the Inferno on his iPhone.” For centuries artists have mined Inferno for raw materials, but now in the sweltering days of the Anthropocene we are enacting it. To note that our present appears as a place where Hell has been pulled up from the bowels of the earth is a superficial observation, for though Dante presciently gives us a sense of what perdition feels like, he crucially also provided a means to identify the wicked.

Denizens of the nine circles were condemned because they worshiped the self over everybody else; now the rugged individualism that is the heretical ethos of our age has made man-made apocalypse probable. ExxonMobil drills for petroleum in the heating Arctic and the apocalyptic QAnon cult proliferates across the empty chambers of Facebook and Twitter; civil wars are fought in the Congo over the tin, tungsten, and gold in the circuit boards of the Android you’re reading this essay with, children in Vietnam and Malaysia sew the clothing we buy at The Gap and Old Navy, and the simplest request for people to wear masks so as to protect the vulnerable goes unheeded in the name of “freedom” as our American Midas Jeff Bezos barely flies to outer space while workers in Amazon warehouses are forced to piss in bottles rather than be granted breaks. Responsibility for our predicament is unequally distributed, those in the lowest circle are the ones who belched out carbon dioxide for profit knowing full well the effects, those who promoted a culture of expendable consumerism and valorized the rich at the expense of the poor. Late capitalism’s operative commandment is to pretend that all seven of the deadly sins are virtues. Literary scholar R.W.B. Lewis describes the “Dantean principle that individuals cannot lead a truly good life unless they belong to a good society,” which means that all of us are in a lot of trouble. Right now, the future looks a lot less like paradise and more like inferno. Dante writes that “He listens well who takes notes.” Time to pay attention.

Bonus Link:

—Is There a Poet Laureate of the Anthropocene?

Image Credit: Wikipedia