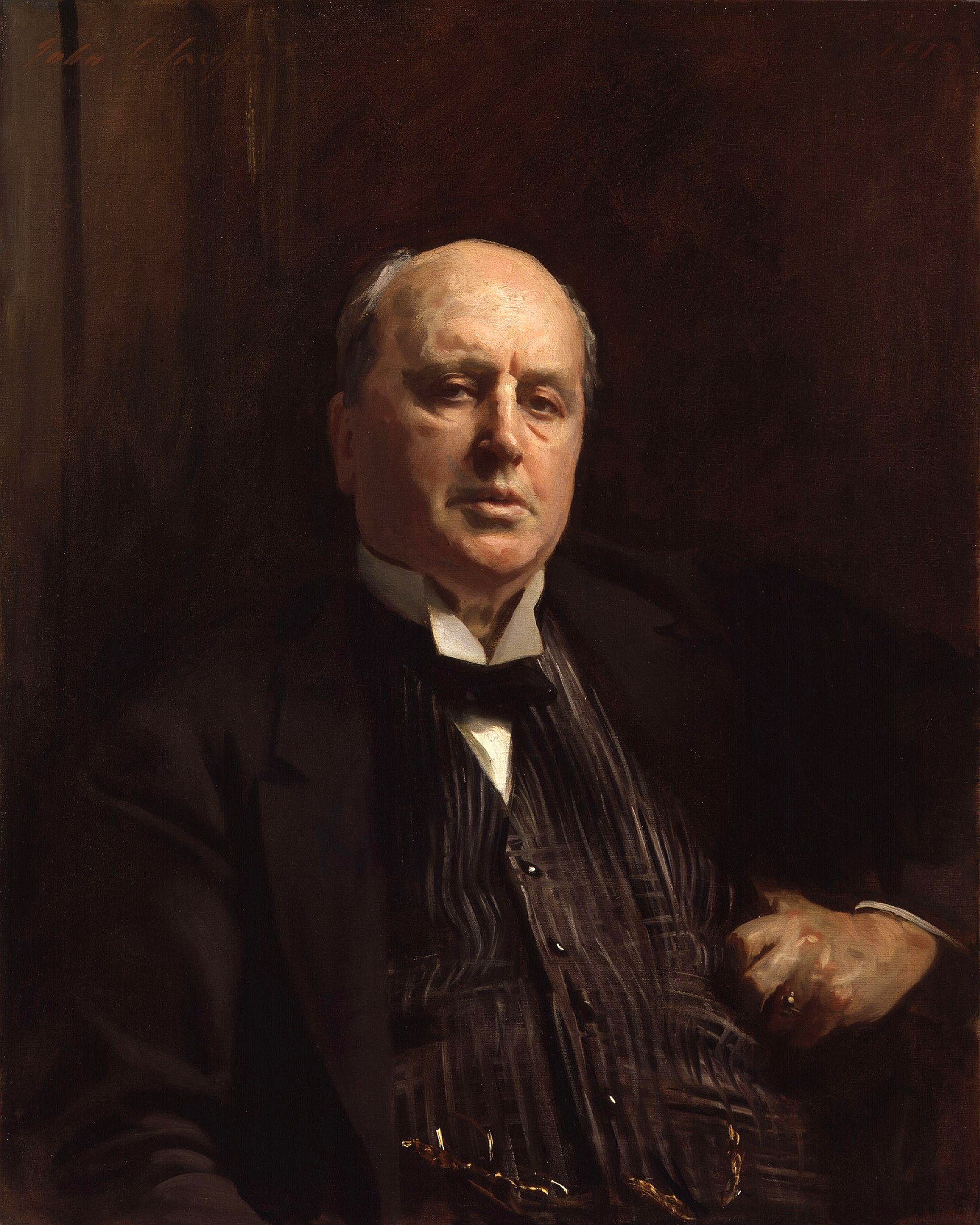

Henry James was one of the most influential English language writers of the modern era. Nominated for a Nobel Prize in Literature three times during his life, James was known for providing in his novels and stories profound portraits of human character, of the relations between genders, and of the moral conflicts and myriad cruelties of middle- and upper-class society in America, England, and Europe. No fiction writer of his time wrote with greater insight about the social and psychological existences of women and girls, nor about the power conferred by money and the vulnerability conferred by lacking it.

James’s 45-year writing career spanned the era of professionalization, and James pursued authorship with unsurpassed professionalism. Devoted to writing, he published a voluminous collection of novels, novellas, stories, plays, travel narratives, autobiographies, biographies, and literary criticism, and produced more than 10,000 letters. In highlighting the distinctiveness of James’s prose, characters, and plots, his contemporary, the editor and author William Dean Howells, noted that James was not, “a novelist…after any fashion but his own,” and would be compelled to create his own readership. The fact that his readership in the 20th century was especially full of fellow writers, among them James Baldwin, Dashiell Hammett, Toni Morrison, and Philip Roth, who all declared his work indispensable to their own, confirms that James introduced something new and lasting into the literary canon.

James has been my own favorite writer ever since I first read The Portrait of a Lady at far-too-young an age to understand it. Still, my instincts told me that I had discovered a unique voice and way of looking at the world, and I kept reading him. As happened for others, James’s writing helped propel me into a career as an English professor, and as a writer myself. Here’s my list of his top 10 works.

Having spent the last few years rereading most of James in preparation for writing my book, I consider The Portrait of a Lady his most perfect novel. It is the ultimate account of how to choose a partner, or how not to, and the novel remains as relevant today in our era of online dating as it was when it was first published. The story of Isabel Archer is James’s first great treatment of the “international theme,” the depictions of Americans going abroad to discover the world and themselves, which became his trademark. Portraying a young American full of promise, possessing looks, intelligence, and idealism, who is brought to England and invested with a fortune by relatives, the novel explores what happens to a woman who is given the freedom to realize her deepest aspirations.

Having spent the last few years rereading most of James in preparation for writing my book, I consider The Portrait of a Lady his most perfect novel. It is the ultimate account of how to choose a partner, or how not to, and the novel remains as relevant today in our era of online dating as it was when it was first published. The story of Isabel Archer is James’s first great treatment of the “international theme,” the depictions of Americans going abroad to discover the world and themselves, which became his trademark. Portraying a young American full of promise, possessing looks, intelligence, and idealism, who is brought to England and invested with a fortune by relatives, the novel explores what happens to a woman who is given the freedom to realize her deepest aspirations.

If The Portrait of a Lady is James’s great account of courtship, The Golden Bowl is his great account of marriage. Set primarily in London, its four principals are a handsome Italian prince, Amerigo, from a family of celebrated ancestry without wealth; an American man of business, Adam Verver, wealthy beyond compare but kinless except for his daughter, Maggie, who has all that money can buy; and Charlotte Stant, an older American friend of Maggie’s from boarding school, extraordinary in every way but financially insecure. The novel portrays two marriages, that of Prince Amerigo and Maggie, and of Adam Verver and Charlotte, and becomes a study of how adultery affects that institution when the Prince and Charlotte rekindle their secret past love affair. James’s favorite topic—wealth versus poverty; rich people buying poor people—is situated within a wider exploration of male versus female natures and the different ways in which the passions and appetites of men and women—familial as well as romantic—support and threaten the social order and the institution of marriage upon which it rests.

If The Portrait of a Lady is James’s great account of courtship, The Golden Bowl is his great account of marriage. Set primarily in London, its four principals are a handsome Italian prince, Amerigo, from a family of celebrated ancestry without wealth; an American man of business, Adam Verver, wealthy beyond compare but kinless except for his daughter, Maggie, who has all that money can buy; and Charlotte Stant, an older American friend of Maggie’s from boarding school, extraordinary in every way but financially insecure. The novel portrays two marriages, that of Prince Amerigo and Maggie, and of Adam Verver and Charlotte, and becomes a study of how adultery affects that institution when the Prince and Charlotte rekindle their secret past love affair. James’s favorite topic—wealth versus poverty; rich people buying poor people—is situated within a wider exploration of male versus female natures and the different ways in which the passions and appetites of men and women—familial as well as romantic—support and threaten the social order and the institution of marriage upon which it rests.

Coupling the experience of illness and suffering with the human proclivity for manipulation and deceit, this novel portrays a dying girl, Milly Theale (a heroine based on James’s beloved cousin from childhood, Minny Temple, who succumbed to tuberculosis at age 24), possessed of wealth she cannot enjoy, and her needy friends, the appealing young Englishwoman, Kate Croy, and the handsome young journalist, Merton Densher, who seek to inherit it. Unbeknownst to Milly, Kate and Merton are committed to each other, but prevented from marrying because of their mutual poverty. Ethical factors aside, the solution from Kate’s perspective is obvious: Densher should conceal his devotion to Kate and court Milly, thus ensuring the ailing girl a few happy last months, and a return to Kate with the capital to marry her properly. From this marvelously succinct scheme is woven a narrative of incomparable complexity.

Coupling the experience of illness and suffering with the human proclivity for manipulation and deceit, this novel portrays a dying girl, Milly Theale (a heroine based on James’s beloved cousin from childhood, Minny Temple, who succumbed to tuberculosis at age 24), possessed of wealth she cannot enjoy, and her needy friends, the appealing young Englishwoman, Kate Croy, and the handsome young journalist, Merton Densher, who seek to inherit it. Unbeknownst to Milly, Kate and Merton are committed to each other, but prevented from marrying because of their mutual poverty. Ethical factors aside, the solution from Kate’s perspective is obvious: Densher should conceal his devotion to Kate and court Milly, thus ensuring the ailing girl a few happy last months, and a return to Kate with the capital to marry her properly. From this marvelously succinct scheme is woven a narrative of incomparable complexity.

James once divulged to a regular correspondent, Mrs. Humphry Ward, that of his novels, The Ambassadors “is, intrinsically, I dare say, the best I have written.” The book is based on emotional advice given by William Dean Howells to a younger man—“live. Live all you can: it’s a mistake not to”—which kindled in James’s mind “the figure of an elderly man who hasn’t ‘lived,’ hasn’t at all, in the sense of passions, impulses, pleasures…He has never really enjoyed—he has lived only for Duty and conscience.” Thus originated the story of Lambert Strether, the reflective middle-aged American enlisted by a wealthy widow, Mrs. Newsome, whom he hopes to marry, to travel to Paris to rescue her son Chad who appears to have lost his way among the dazzling attractions of the French capital. What happens to Mrs. Newsome’s “ambassador” when confronted with “the vast bright Babylon” of French civilization provides the novel’s chief dramatic action.

James once divulged to a regular correspondent, Mrs. Humphry Ward, that of his novels, The Ambassadors “is, intrinsically, I dare say, the best I have written.” The book is based on emotional advice given by William Dean Howells to a younger man—“live. Live all you can: it’s a mistake not to”—which kindled in James’s mind “the figure of an elderly man who hasn’t ‘lived,’ hasn’t at all, in the sense of passions, impulses, pleasures…He has never really enjoyed—he has lived only for Duty and conscience.” Thus originated the story of Lambert Strether, the reflective middle-aged American enlisted by a wealthy widow, Mrs. Newsome, whom he hopes to marry, to travel to Paris to rescue her son Chad who appears to have lost his way among the dazzling attractions of the French capital. What happens to Mrs. Newsome’s “ambassador” when confronted with “the vast bright Babylon” of French civilization provides the novel’s chief dramatic action.

James’s only long novel set exclusively in America, The Bostonians is steeped in the rhetoric and themes of the Civil War, and concerns the social developments that defined the post-war era of Reconstruction, including the rise of consumerism, advertising, and celebrity; the ongoing tension between democratic values and class stratification in the expanding capitalist nation; and changing gender roles and ideas about sexuality. Given its emphasis on the limitations and even destructiveness of traditional ideas about men and women, The Bostonians can be viewed as a rejoinder to The Portrait of a Lady, which reimagines its predecessor as an anti-marriage novel dramatizing the need for feminist consciousness raising. However one interprets its gender politics, The Bostonians is the first major American novel to take the feminist movement seriously, and to present lesbian sexuality with real sensitivity.

James’s only long novel set exclusively in America, The Bostonians is steeped in the rhetoric and themes of the Civil War, and concerns the social developments that defined the post-war era of Reconstruction, including the rise of consumerism, advertising, and celebrity; the ongoing tension between democratic values and class stratification in the expanding capitalist nation; and changing gender roles and ideas about sexuality. Given its emphasis on the limitations and even destructiveness of traditional ideas about men and women, The Bostonians can be viewed as a rejoinder to The Portrait of a Lady, which reimagines its predecessor as an anti-marriage novel dramatizing the need for feminist consciousness raising. However one interprets its gender politics, The Bostonians is the first major American novel to take the feminist movement seriously, and to present lesbian sexuality with real sensitivity.

Like many contemporary intellectuals, Henry James and his brother William, the Pragmatist philosopher and psychologist, took ghosts seriously. They were friendly with Frederic W.H. Myers, who headed The Society for Psychical Research, and Henry was recorded in the minutes of a Society meeting in London reading a report on behalf of his absent brother about a female medium who was occasionally overtaken by the spirit of a dead man. Concerns about the boundaries between life and death, and the influence exerted by the dead upon the living are central to the plot of The Turn of the Screw. The question that confronts every reader of the novella is whether the ghosts of Miss Jessel, the governess, and Peter Quint, the gardener, are real or figments of the current governess’s imagination. While some believe in them wholeheartedly and others deem them hallucinations of an hysterical governess, James’s narrative insists on leaving the question open.

Like many contemporary intellectuals, Henry James and his brother William, the Pragmatist philosopher and psychologist, took ghosts seriously. They were friendly with Frederic W.H. Myers, who headed The Society for Psychical Research, and Henry was recorded in the minutes of a Society meeting in London reading a report on behalf of his absent brother about a female medium who was occasionally overtaken by the spirit of a dead man. Concerns about the boundaries between life and death, and the influence exerted by the dead upon the living are central to the plot of The Turn of the Screw. The question that confronts every reader of the novella is whether the ghosts of Miss Jessel, the governess, and Peter Quint, the gardener, are real or figments of the current governess’s imagination. While some believe in them wholeheartedly and others deem them hallucinations of an hysterical governess, James’s narrative insists on leaving the question open.

7. “The Beast in the Jungle”

The story of John Marcher, a man who devoutly withholds himself from ordinary experience as he awaits the distinguished fate he believes his due, is the most admired and frequently anthologized of James’s stories. Ambition, grandiosity, and the conviction that he is special, different from the multitude, are Marcher’s chief, indeed only, interests. Propelled by the expectation of an event that never happens, Marcher’s final view of himself reveals “the beast” as his own failure to accept what life offered, the love of May Bartram, who herself has lived by loving him for himself. James thought deeply about the ways in which avoiding human connection impoverished existence, and much of that thinking bears fruit in this magnificent story.

This superb novella is about an accomplished Manhattan physician, Dr. Austin Sloper, a widower raising his daughter, Catherine, alone. The plot centers on Dr. Sloper’s ambivalence toward Catherine, who is mediocre in every way. It is precisely this mediocrity that make the attentions of Morris Townsend, the handsome young fortune hunter she meets at a party when she is 22, suspect. After it is revealed that Townsend, having gone through his own small fortune, now sponges off his sister, a struggling widow with five children, Dr. Sloper forbids Catherine from seeing her suitor. Thus Catherine, who has fallen quickly in love, is caught between her passion for the handsome young man whose courtship is so unexpected, and her filial love, which are both genuinely powerful.

This superb novella is about an accomplished Manhattan physician, Dr. Austin Sloper, a widower raising his daughter, Catherine, alone. The plot centers on Dr. Sloper’s ambivalence toward Catherine, who is mediocre in every way. It is precisely this mediocrity that make the attentions of Morris Townsend, the handsome young fortune hunter she meets at a party when she is 22, suspect. After it is revealed that Townsend, having gone through his own small fortune, now sponges off his sister, a struggling widow with five children, Dr. Sloper forbids Catherine from seeing her suitor. Thus Catherine, who has fallen quickly in love, is caught between her passion for the handsome young man whose courtship is so unexpected, and her filial love, which are both genuinely powerful.

9. Prefaces to the New York Edition

The 18 prefaces James wrote for the New York Edition of his Collected Works amount to a primer on literary method: the importance of point of view and establishing the fiction’s central consciousness, the attention to narrative design and the building blocks of plot, and the organic integrity of the work, each with its own necessary size and shape. James’s goal was to devise a method and theory of fiction using his vast experience as a writer and applying his considerable critical skills to his own major works. The project was at once distanced, an objective investigation of his best fiction, and intimate, a recollection of his subjective state while writing. Without liking James, without ever having read him, legions of aspiring writers in the 20th and 21st centuries have internalized these legendary methods. This is in no small part because the prefaces present novelistic practice as the most significant of human endeavors.

James’s return to the U.S. following a 20-year absence intensified qualms about his native land that had motivated his self-exile. Much of what James writes about his rediscovered country in his famous travelogue is acute. He sees the impact of “creative destruction” everywhere, but finds few compensations for this repudiation of tradition. He hears “much talk—but no conversation.” The art of living is nowhere to be found, a consequence, James asserts, of the prevailing American obsession with profit and money-making. The paradox is how this dominant value makes the country an unusually elastic organism for assimilating people from foreign lands. Equally important is James’s insight that in America being from elsewhere is a fundamental national characteristic. In a country composed like no other of waves upon waves of immigrants, being different from others is the norm.

James’s return to the U.S. following a 20-year absence intensified qualms about his native land that had motivated his self-exile. Much of what James writes about his rediscovered country in his famous travelogue is acute. He sees the impact of “creative destruction” everywhere, but finds few compensations for this repudiation of tradition. He hears “much talk—but no conversation.” The art of living is nowhere to be found, a consequence, James asserts, of the prevailing American obsession with profit and money-making. The paradox is how this dominant value makes the country an unusually elastic organism for assimilating people from foreign lands. Equally important is James’s insight that in America being from elsewhere is a fundamental national characteristic. In a country composed like no other of waves upon waves of immigrants, being different from others is the norm.

Bonus Links:

—Henry James for Every Day of the Year

—Henry James and the Joys of Binge Reading

—The Great Late Henry James

This piece was produced in partnership with Publishers Weekly.