Here’s a quick look at some notable books—new titles from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Peter Ho Davies, Anna North, and more—that are publishing this week.

Want to learn more about upcoming titles? Then go read our most recent book preview. Want to help The Millions keep churning out great books coverage? Then become a member today.

In the Land of the Cyclops by Karl Ove Knausgaard

In the Land of the Cyclops by Karl Ove Knausgaard

Here’s what Publishers Weekly had to say about In the Land of the Cyclops: “In this dense and thought-provoking essay collection, Knausgaard (My Struggle) once again displays his knack for raising profound questions about art and what it means to be human. While Knausgaard brings complexity to his studies of paintings and photographs, analyzing the function of myths in German artist Anselm Kiefer’s paintings and wondering ‘how are we to understand’ Francesca Woodman’s mid-20th-century photographs, the essays pick up when Knausgaard writes about literature. Among the most successful pieces are ‘To Where the Story Cannot Reach,’ which contains his musings on craft and his relationship with his editor (whom Knausgaard has ‘absolute trust in’); the title essay, which asks, ‘What is literary freedom?’ when writers are told ‘what they should and shouldn’t write about’; and an exploration of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (‘If [it] were published today, there is no doubt in my mind that tomorrow’s reviews would be ecstatic’). In ‘All That Is Heaven,’ he eloquently compares art to dreams, writing, ‘art removes us from and draws us closer to the world, the slow-moving, cloud-embraced matter of which our dreams too are made.’ Though unevenly paced, the volume tackles knotty subjects and offers nuggets of brilliance along the way. These wending musings will be catnip for Knausgaard’s fans.”

A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself by Peter Ho Davies

A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself by Peter Ho Davies

Here’s what Publishers Weekly had to say about A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself: “Davies (The Fortunes) delves into fatherhood in his thoughtful latest, intertwining musings on pregnancy, marriage, family life, and work. The unnamed narrator, a writer and creative writing professor, makes the difficult decision with his wife to terminate their pregnancy after the fetus tests positive for mosaicism and their doctor gives them a long list of potential birth defects. A subsequent successful pregnancy brings new fears over their son’s development, as the couple processes their internalized shame over the abortion and their son’s potential autism (‘Abortion is shameful, because pregnancy is shameful, because sex is shameful, because periods are shameful. It almost makes me relieved we had a boy,’ the wife says). Davies explores their emotions in unflinching honesty, as the narrator contends with lingering fears over getting their son tested for autism. Davies’s smooth prose and ruminations on language (a synonym for ‘imagine,’ the narrator considers, is also ‘to conceive’) are the stars of this work. While an anticlimactic, philosophical conclusion somewhat undermines the narrator’s character development after he embraces his role as a father, it resonates with the key theme of paradoxes. Davies’s meditation on the complexities of parenthood is at once celebration and absolution, finding truth in human contradictions.”

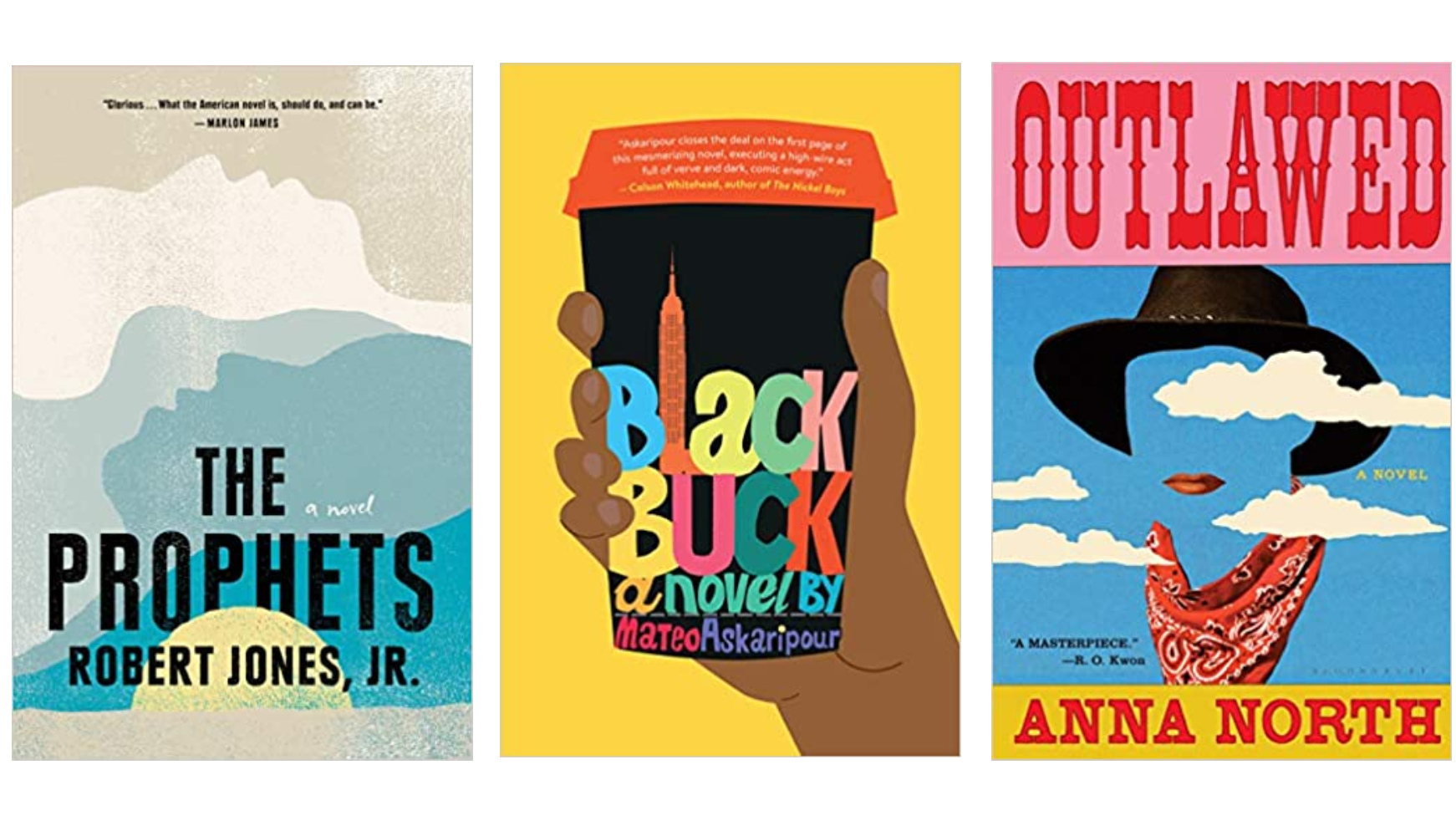

The Prophets by Robert Jones

The Prophets by Robert Jones

Here’s what Publishers Weekly had to say about The Prophets: “This is a first novel, but I hope it took years and years to write since it is so powerful and beautiful. It is an antebellum story of a flourishing Mississippi plantation some people refer to as ‘Nothing’ and others call ‘Elizabeth,’ the name of the owner’s mother. This is a love story of two gay enslaved men, Isaiah and Samuel (not their original African names), who’ve been assigned to look after the horses and who work together in perfect harmony in the barn.

With astonishingly real details, Jones creates a convincing picture of slave life, everything from transportation in ships (where those captives who had died from hunger or wounds or disease were just thrown overboard) to the arrival, in this case, at a vast cotton plantation, where they are branded, forced with whipping to work harder and faster, insulted, mocked and, if they’re female, raped.

Jones’s women are all sharply delineated, starting with the ‘king’ of a tribe in Africa, a woman-warrior who lives with her several wives. The main women on the plantation—Be Auntie, Sarah, Puah, Essie—have their own clearly delineated identities and complex psychologies. What is unprecedented in this novel is its presentation of the two gay male slaves, each endowed with his own personality, which never merges with a stereotype.

In fact, Jones’s compassionate understanding extends even to the whites (who are referred to as toubab, a Central African locution): ‘When they approached, she had figured out something that had been like a splinter in her foot: the easy thing to believe was that toubab were monsters, their crimes exceptional. Harder, however, and even more frightening, was the truth: there was no such thing as monsters. Every travesty that had ever been committed had been committed by plain people and every person had it in them.’ Which is not to say Jones lets his slave owners off easily. They were hypocritical Christians, sadists who raped their chattel, who worked their slaves until they could do no more and called them ‘lazy’: ‘They stepped on people’s throats with all their might and asked why the people couldn’t breathe.’ Whites kidnapped black children and then called slave parents ‘incapable of love.’

The lyricism of The Prophets will recall the prose of James Baldwin. The strong cadences are equal to those in Faulkner’s Light in August. Sometimes the utterances in the short interpolated chapters seem as orphic as those in Thus Spake Zarathustra. If my comparisons seem excessive, they are rivaled only by Jones’s own pages and pages of acknowledgments. It seems it takes a village to make a masterpiece.”

Black Buck by Mateo Askaripour

Black Buck by Mateo Askaripour

Here’s what Publishers Weekly had to say about Black Buck: “Askaripour eviscerates corporate culture in his funny, touching debut. Darren, a young Black man, lives with his mom in Brooklyn’s Bed-Stuy neighborhood and manages a midtown Manhattan Starbucks. He’s content with his life and girlfriend, Soraya, but people tell him he could do more—he was valedictorian at Bronx Science, after all. Opportunity knocks when Darren persuades Rhett Daniels, the CEO of tech startup Sumwun and a Starbucks regular, to change his usual order. Rhett is impressed (his response: ‘Did you just try to reverse close me?’) and invites Darren to an interview, which leads to a sales job before he understands what the company actually does (it’s a platform for virtual therapy sessions). Darren makes good money, but struggles to keep up his commitments to his family and Soraya as Rhett pulls him into heavy after-hours partying. When an employee in China is charged with murder, Sumwun crashes, and so does Darren’s life. In an author’s note, Askaripour suggests the book is meant to serve as a manual for aspiring Black salesmen, and the device is thrillingly sustained throughout, with lacerating asides to the reader on matters of race. (‘The key to any white person’s heart is the ability to shuck, jive, or freestyle. But use it wisely and sparingly.’) Darren, meanwhile, is alternately said by various white characters to resemble Malcolm X, Sidney Poitier, MLK, and Dave Chappelle, while he struggles to hold onto a sense of self, which the author conveys with a potent blend of heart and dramatic irony. Askaripour is always closing in this winning and layered bildungsroman.”

After the Rain by Nnedi Okorafor

After the Rain by Nnedi Okorafor

Here’s what Publishers Weekly had to say about After the Rain: “Upon Chioma’s arrival to the remote Nigerian village where her great-aunt and grandma live, heavy, unseasonable rain begins to fall, in this vibrant, succinct graphic adaptation by Jennings (Kindred) and Brame (Baaaad Muthaz) of Okorafor’s short story ‘On the Road.’ On the third night of rainfall, a boy with brains busting out of his broken skull calls on Chioma and declares her ‘it.’ A Chicago detective, Chioma isn’t easily shaken by gore, but even she isn’t able to grasp the strange happenings that follow, the unknowable entity that stalks her, and what that entity will do when it catches her. Though, the original is open to interpretation, the adaptation, which was created in conjunction with Okorafor, outright states a moral to the story: ‘I am Nigermerican… and where those two parts meet is where I am whole again,’ slightly marring the enigma of the ending. But Brame’s bold and arresting use of color and shading lends an unnerving atmosphere to the setting, while his attention to facial expressions injects the panels with emotion. This mostly faithful adaptation honors Okorafor’s voice and paints a potent portrait of Nigeria and its folklore.”

Outlawed by Anna North

Outlawed by Anna North

Here’s what Publishers Weekly had to say about Outlawed: “North’s knockout latest (after The Life and Death of Sophie Stark) chronicles the travails of a midwife’s daughter who joins a group of female and nonbinary outlaws near the end of the 19th century. Eighteen-year-old newlywed Ada, unable to conceive a child, fears she will be accused of witchcraft, a fate common to the women in her Dakota territory community. After Ada’s former friend has a miscarriage and accuses Ada of casting a spell on her, Ada’s mother helps her flee to a nunnery, where a Sister suggests she join a nearby gang known as Hole in the Wall. Ada becomes a ‘doctor’ to the motley group led by the Kid (to whom no gender pronouns are attributed—’‘Not he, not she,’ Elzy said. ‘The Kid is just The Kid’’). The outlaws plan to create a town where nonconforming people can belong. The tense plot takes many turns through Ada’s increasingly violent adventures with the gang, beginning with a botched holdup of a wagon laden with gold. As the novel barrels toward a surprise ending, it’s further strengthened by Ada’s voice and reflections, which preserve a sense of immediacy: ‘distances that had once seemed vast were now so small that my enemies could cross them in an instant.’ The characters’ struggles for gender nonconformity and LGBTQ rights are tenderly and beautifully conveyed. This feminist western parable is impossible to put down.”