Criticism isn’t generally thought of as escapist, but it’s where I turned when I needed a break during the early, childcare-less days of the pandemic. I realize this may sound counterintuitive, but hear me out; there’s a place farther afield than the imagined cities of Science Fiction and Fantasy—the realm of pure thought. What I wanted this year was for reading to render me bodiless. Aerosols aren’t the concern of a brain in a vat.

The first book to succeed on this front was Out the Vinyl Deeps: Ellen Willis on Rock Music. As a self-proclaimed amateur Dylanologist, I’m ashamed to say I’d never read Willis before. Her 1967 Cheetah piece on the many masks of R. Zimmerman—a 15,000 word treatise that got her hired as The New Yorker’s first rock critic—is arguably the best thing written on this most shopworn of subjects, an exemplar of lucid prose and original thought. Willis convincingly suggests that Dylan’s great subject is celebrity, and that his work shares as much with Andy Warhol’s as it does with Woody Guthrie’s. She argues against Dylan as poet (sorry Nobel committee), and makes the case for his true genius living in the synthesis of writing and performance, “a unity of sound and word.” Though the Dylan piece came early in Willis’s short career as a music critic—she went on to focus on feminism and politics—her mission was already apparent. Willis strove to demystify the sixties even as they were unfolding, and to pull back the curtain on rock and roll mythology to get a closer, truer look at both the music and the star-maker machinery that commodified and sold it. “Rebellion,” she reminds us, “is not the same thing as revolution.”

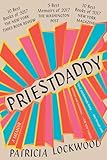

My other embarrassingly belated discovery this year was the poet, critic, and soon-to-be novelist Patricia Lockwood, whose regular columns for The London Review of Books sent me scrambling to my mailbox in anticipation (though only because it took me months to figure out how to link my print subscription to an online account.) Lockwood’s criticism triumphs through a different kind of unity, the rare fusion of magnanimity with cold critical judgment. The result is either a loving brutality or a pitiless ardor, I’m not sure which. Either way it’s thrilling to read. Nothing in recent memory has made me laugh harder than her recent piece on Nabokov, the “young aristocrat, 75 percent composed of foraged mushrooms.” The only contender is her 2019 piece on Updike, “a God who spends four hours on the shading on Eve’s upper lip, forgets to give her a clitoris, and then decides to rest on a Tuesday.” When literary Twitter recently spent a week arguing over the makings of a successful metaphor, I fantasized about shoving these pieces under everyone’s noses and stopping the argument dead in its tracks. Better still, I’d make them read Priestdaddy, Lockwood’s memoir of life with her eccentric father, a Catholic priest who rarely wears pants and thinks he’s the second coming of Eddie Van Halen. I found the book so dazzling I can only assume that its author, as a budding teenage poet, once crept out of the rectory and down to the crossroads, where she made a Robert Johnson—style deal with the devil.

More from A Year in Reading 2020

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005