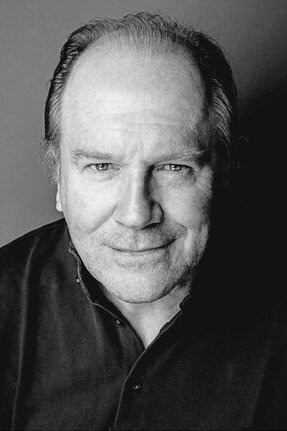

William Boyd was 16 in 1968, the year his new novel, Trio, is set. It was a moment of change and social revolution, but Boyd’s impetus to write the novel—which centers on a shoot in Brighton, England, for a fictional film titled Ladder to the Moon—was driven by his teenage recollections of an era that was much less political.

During a phone call from his London home, Boyd says he was living in the U.K. in 1968 and then in 1969, he left for Paris. There, at 17, he met numerous people “who had been on the barricades” the previous May, and he soon realized that “the world was going to go to hell on a handcart.” But this wasn’t the feeling in the U.K.

“In Britain we were in a swinging ’60s bubble,” Boyd explains. The mood of fun and frivolity was expressed in a string of zany and largely subpar films like A Hard Day’s Night and the lesser-known Can Heironymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe and Find True Happiness? The latter, he notes, was a flop, but it served as an inspiration for the novel. He wanted to “have a swinging ’60s movie being made in Brighton, and around it the real world creeps in.”

“In Britain we were in a swinging ’60s bubble,” Boyd explains. The mood of fun and frivolity was expressed in a string of zany and largely subpar films like A Hard Day’s Night and the lesser-known Can Heironymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe and Find True Happiness? The latter, he notes, was a flop, but it served as an inspiration for the novel. He wanted to “have a swinging ’60s movie being made in Brighton, and around it the real world creeps in.”

Trio focuses on three characters—the film’s producer, its leading lady, and the director’s wife—who must navigate the bizarre world of the film and the reality beyond it. It follows them over the course of an increasingly chaotic shoot.

Boyd has 16 novels to his name and is also an accomplished screenwriter and producer. His screenwriting credits include 1992’s Chaplin, starring Robert Downey Jr., and the 1994 adaptation of his debut novel, A Good Man in Africa (the book version won the Whitbread Book Award for first novel in 1981). Given this, he knows the world of Trio well, and the on-set machinations are a highlight of the book.

Boyd has 16 novels to his name and is also an accomplished screenwriter and producer. His screenwriting credits include 1992’s Chaplin, starring Robert Downey Jr., and the 1994 adaptation of his debut novel, A Good Man in Africa (the book version won the Whitbread Book Award for first novel in 1981). Given this, he knows the world of Trio well, and the on-set machinations are a highlight of the book.

Paradoxically, Trio also betrays how little film sets have changed since the ’60s. There are still incomprehensible, expensive delays; egocentric male directors; and intense on-set romances.

Boyd acknowledges that this is partly to do with the essentially patriarchal traditions of the film world. “There are some differences,” he notes. “Joan Collins used to do her own make up. There was no catering or lunch breaks. But the fundamentals of life on the set—the temperaments, the tantrums, the things that can go wrong so easily—are exactly as true in 1968 as 2020. For a long time the movie business was a boys’ town. I’m old enough, and have had the experience to see how it’s slowly changed. Certainly in 1968, it was very patriarchal, and that’s only really started to change in the last few years.”

All three of the main characters in Trio are oppressed by the weight of this patriarchy in different ways. The producer, Talbot Kydd, is secretly gay. Anny Viklund, the film’s star, is being threatened and exploited by a succession of bad boyfriends. And Elfrida Wing, the director’s wife, endures her husband’s affair with the film’s screenwriter.

The misery experienced by Elfrida, who is also working on a novel, has an impact. Tormented by her marriage, alcoholism, and writer’s block, she becomes dangerously paranoid. She is unable to distinguish her husband’s lies from reality and is convinced she can see worms beneath her skin. There are recurring, devastating scenes in which she rewrites the opening paragraph of her new novel and then starts drinking again.

Boyd reveals that Elfrida is loosely based on a real-life novelist and poet named Rosemary Tonks, who disappeared from public view after an auspicious literary debut. Tonks was later discovered to have entered the religious life—a decision that fascinated Boyd. “It haunted me that someone could do that,” he says, “and I was interested to know more, too, about writer’s block.”

It is notable that the most functional and self-possessed character in Trio is a man who has no links to the film world—a private detective named Ken Kincaid, who is gay and at ease with himself. Through Ken’s eyes, we have some perspective on how strange this world of make-believe has become.

Boyd still has great affection for the film industry but says he is relieved to have the option to withdraw from it when necessary, into the world of novel writing. “My saving grace is that I have the two worlds. I really enjoy collaborating. I have more friends in the filmmaking business. I now coproduce. But I’m so pleased there are times that I can say cheerio and write.”

This affection is evident in the book’s many period details. Boyd says research is key to all of his writing. He can spend 18 months to two years preparing for a new novel. In the case of Trio, he read copiously.

“I’ve about 80 to 100 books about this era on everything from Jean Seberg, who was a model for Anny [the actor in Trio], to French politics,” Boyd says. “I think of a novelist as a magpie rather than a scholar. Anything bright that catches your eye can be brought into the work.”

Boyd explains that part of the novelist’s art is deciding what to use and what to discard. “I’ve taught myself that you have to throw out 90 percent of the research, and that is part of the discipline, too,” he says. As time has gone by, he adds, his nose for the right detail has improved.

For Boyd, the past is a more attractive setting for his fiction than the present. “You avoid any built-in obsolescence,” he says. “Contemporary novels have a terrible problem of dating very quickly. They can date. In the recent past, everything is fixed.”

Boyd’s 2002 novel  Any Human Heart was written as a series of journals by a writer named Mountstuart who lived from 1906 to 1991. It includes recollections of many significant historical events, such as the Wall Street crash of 1929 and WWII. It has sold, according to NPD BookScan, more than 58,000 print copies in the U.S. and was shortlisted for the Booker and the International Dublin Literary Award.

Any Human Heart was written as a series of journals by a writer named Mountstuart who lived from 1906 to 1991. It includes recollections of many significant historical events, such as the Wall Street crash of 1929 and WWII. It has sold, according to NPD BookScan, more than 58,000 print copies in the U.S. and was shortlisted for the Booker and the International Dublin Literary Award.

For his next project, Boyd is going to embark on what he describes as another “whole-life novel”—a novel that portrays the entirety of a character’s life. It will be set “completely in the 19th century,” he says, and be “very ambitious,” extending beyond 500 pages.

“Unlike Elfride, I haven’t experienced writer’s block. Yet.”

Bonus Links:

—Identity Crisis: William Boyd’s Ordinary Thunderstorms

—Spy Story: A Review of William Boyd’s Restless

Image Credit: Trevor Leighton

This piece was produced in partnership with Publishers Weekly.