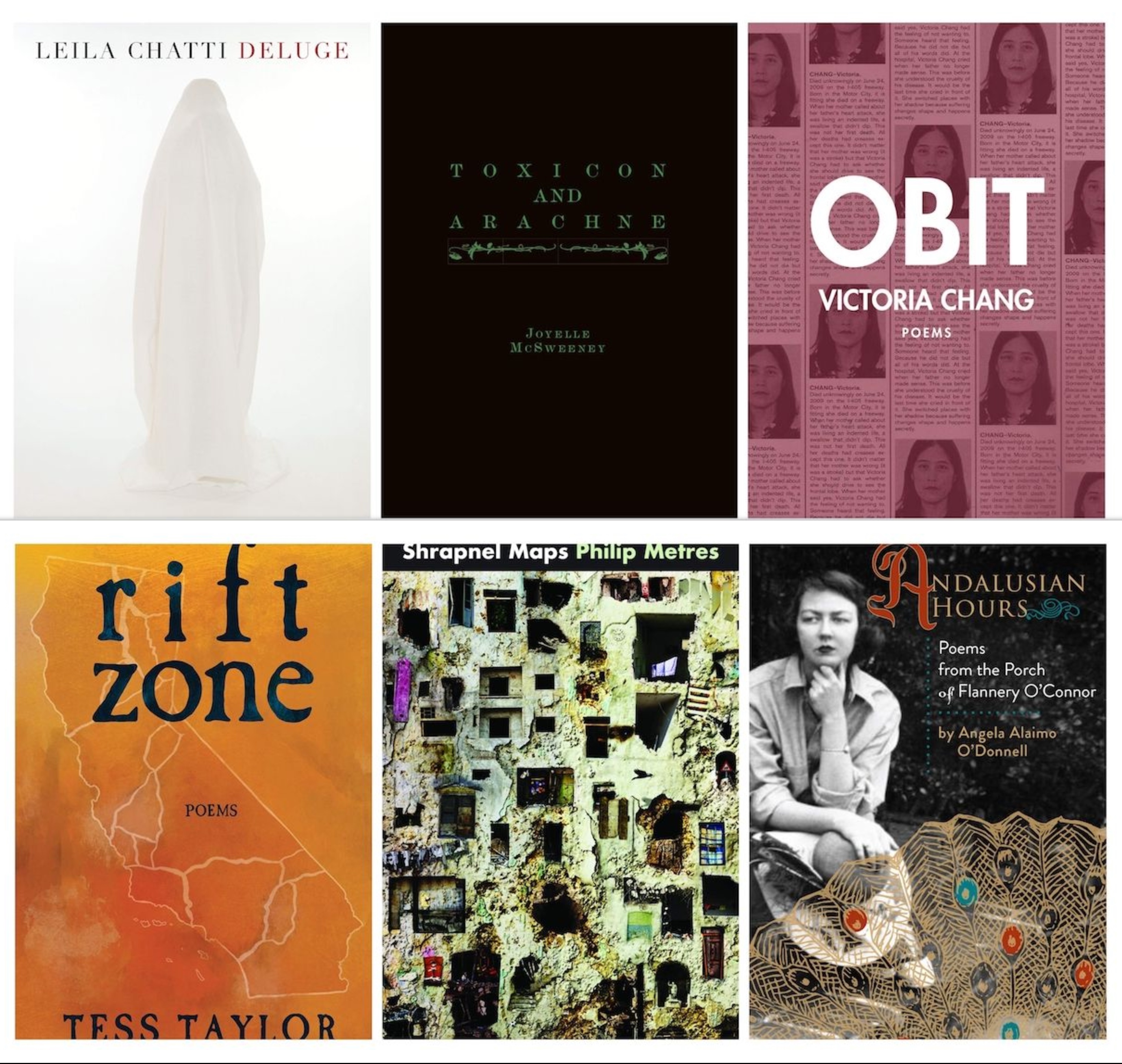

Here are six notable books of poetry publishing this month.

Deluge by Leila Chatti

Deluge by Leila Chatti

A stunning debut. Chatti enters the Marian tradition of literature with fury, joining Mary Szybist’s Incarnadine as recent works that offer new theory and theology toward the literary Mary. In this God-teeming book, Chatti considers not only herself against Mary—the only woman mentioned by name in the Qur’an—but all women present and historical against the Marian figure and image. Raised Muslim by her father, her “mother’s family is deeply Catholic,” and she was drawn to the Marian identity across those two faiths, particularly what Mary says in the Qur’an, while giving birth: “Oh, I wish I had died before this and was in oblivion, forgotten.” In Deluge, Chatti emerges from that line with a synthesis of body and spirit, secret and wish, miracle and literal body. “Truth be told,” she starts the first poem, “I like Mary a little better / when I imagine her like this, crouched / and cursing, a boy-God pushing on / her cervix (I like remembering / she had a cervix, her body ordinary / and so like mine).” In other poems, Chatti steps within Mary’s identity, imagining the visitation by Gabriel, “rude / as a dream,” and feeling regret over keeping “my tongue in my mouth.” “Perhaps I’d have been / better off,” she ends the poem, “to be wary, but I’d been waiting so long / to hear God speak—I hadn’t thought to think // of what he might tell me.” In one of several poems titled “Annunciation,” Chatti’s identity folds into Mary as they become one woman who, throughout the book, encounter men (doctors, lovers, more): “I have come to accept the story of my own / obedience.” Each line here a testimony: “You sent a man I could not / look at fully, or touch, he was a flame / which spoke, and I could not / be afraid.”

Toxicon and Arachne by Joyelle McSweeney

Toxicon and Arachne by Joyelle McSweeney

McSweeney is one of our most dynamic poets of theme, mood, and syntax, and this new paired collection unifies those ranges in a most powerful fashion. Toxicon examines our necropastoral, digital landscape: “What is it to survive / or lie cossetted in a coma / a bombilation of effects / a thicket of causes—”. McSweeney’s lines and concerns always intersect and interject, as in “Axis”: “If there is an axis / let it run through my heart / and the heart of my horse // waving this lance like a lancet / toward an abscess in the breast / of the sky, gimlet-eye / into which a planet has just swum.” In ““For Alexandra Negrete,” an elegy for a murdered Mexican worker, she writes “the sound we call static / is really full of activity / percussing / and injuring itself / and sending the message back / through the sea shell / to the ear canal.” In McSweeney’s poetry, everything surrounding us is active, alive, fervent. Our bodies spasm, jerk, contort: out-of-control, dislocated. Arachne, the second paired text, is a soul-moving song to her daughter, who died so young her spirit rises from these pages: “I who feel so obsolete / An obol and an obelisk / a baffle and a baselisk / With one daughter dead and two living.” McSweeney leaves grief open and breathing: an affirmation that grief can somehow sustain us, give us reason to persevere.

Obit by Victoria Chang

Chang is consistently a poet who resurrects mediums, her work living within surprising spaces and forms, and both exposing and surpassing the possibilities for those structures. In prose poems that channel the obituary style, Chang wonders what death might mean for the living: how lives are filled with passings and grief, and how such pain might remind us what it means to be alive. Chang has the rare poetic talent to follow the edges of dark comedy to find sentiment rather than irony. Her parents loom large here. Her father’s stroke appears in the first poem, and he returns often, as in a voicemail that is poorly documented: “The Transcription Beta could not transcribe dementia. My father really said, I’ll fold the juice, not I love you. Is language the broom or what’s being swept?” In a later poem, she brings her father to an arcade, and, “As if he were visiting his past self in prison, [he touched] the clear glass at his own likeness.” She ends the poem: “He called my dead mother over to see his score, hand waving at me. What happens when the shadow is attached to the wrong object but refuses to let go? I walked over because I wanted to believe him.” When her mother died, and Chang told her children, “the three of us hugged in a circle, burst into tears. As if the tears were already there crying on their own and we, the newly bereaved, exploded into them.” A book that might help us understand the confounding place of loss in our lives.

Rift Zone by Tess Taylor

Rift Zone by Tess Taylor

California: pastoral, urban, suburban—home to myth and magic. Taylor’s book is geologic in concept and theme, both panoramic and particular (her lines are ripe with texture, as in: “Blackberries choke the bike path; / schoolboys squall like gulls or pigeons.”). There’s a self-awareness of identity and place that enables Taylor to write odes that double as measured reflections, as with “Berkeley in the Nineties”: “Too late for hippie heyday / & too young to be yuppies / we wandered creeksides & used bookstores.” Later: “We could say systemic racism / but couldn’t name yet how our lives were implicated.” This youthful freedom and folly is juxtaposed with another California: “In every sale, a list of ways / your home could be destroyed. / Flood, earthquake, fire.” Disruption is inevitable here, and will be watched by the redwoods that “overlook / your fragile real estate.” “Train Through Colma” wonders about the future: “But will anyone teach / the new intelligence to miss / the apricot trees // that bloomed each spring / along these tracks?” Taylor hits the fine note of how nostalgia evolves into worry and lament: “When the robots have souls, / will they feel longing? / When they feel longing, // will they write poems?”

Shrapnel Maps by Philip Metres

Shrapnel Maps by Philip Metres

“Poetry’s slowness,” Metres has written, “its ruminativity, enables us to step back from the distracted and distracting present, to ground ourselves again through language in the realities of our bodies and spirits and their connections to the ecosystems in which we find ourselves.” Metres has emerged as one of the leading Catholic poet-activists. A previous book, Sand Opera, “began as a daily Lenten meditation, working with the testimonies of the tortured at Abu Ghraib, to witness to their suffering; it became an attempt to find a language that would sight (to render visible) and site (to locate in the geographical imagination) the war itself, constantly off-screen.” Shrapnel Maps exists along this continuum as a book that feels itinerant, longing for discovery, and fascinating in its conception of neighbor (close and far). “One Tree,” the first poem, arrives like an introductory parable: “They wanted to tear down the tulip tree, our neighbors, last year.” The tree shadowed their vegetable patch. “Always the same story,” the narrator observers: “one tree, not enough land or light or love.” In “A Concordance of Leaves,” the first extended sequence of the book, the narrator and his family go to Toura in the West Bank for his sister’s wedding: “sister soon you will be written / alongside your future.” She “will find another way / through rutted olive // orchards & soon new sisters / will soften your feet with oil.” “Theater of Operations,” a sequence of sonnets that consider a hypothetical suicide bombing, jar and illuminate: “My tongue wrestles with new words— // so why do I taste metal, like blood in the mouth? / Why do I feel so alive, this close to death?” A riveting, ambitious book.

Andalusian Hours: Poems from the Porch of Flannery O’Connor by Angela Alaimo O’Donnell

O’Connor has a worthy medium in O’Donnell, who has been a perceptive and honest examiner of one of our finest fiction writers (Radical Ambivalence: Race in Flannery O’Connor is nicely paired and contrasted with The Province of Joy: Praying with Flannery O’Connor). In this new book, each poem is paired with a line from her letters, stories, or essays. Readers of O’Connor’s correspondence know that she was deft, sarcastic, contemplative, curious: a unique mind that was equally (and paradoxically) at home writing for diocesan publications as she was appearing in Esquire. O’Donnell brings her alive in these pieces. In “Flannery in Iowa,” O’Connor reflects on the “wishes / I brought to that little church. / The swords I laid down on that alter.” In graduate school, “Marooned and alone, I went there in search / of who I needed to become.” The classic line about the Eucharist that O’Connor quipped to Mary McCarthy—”Well, if it’s a symbol, to hell with it”—is dramatized here: “A country and a Catholic girl, I’d come / to the Big City to learn to write, / not to lose the only faith I’d known / and could not live without.” “Compline,” the penultimate section of the book, is melancholy and pensive, and considers O’Connor’s life cut short at 39: “These are my last days, that’s pretty clear— / though sometimes at night I still feel the call / of this life.” A necessary collection for fans of O’Connor, and a welcome introduction to those who want to understand the continuing pull of a truly original writer.