This post was produced in partnership with Bloom, a literary site that features authors whose first books were published when they were 40 or older.

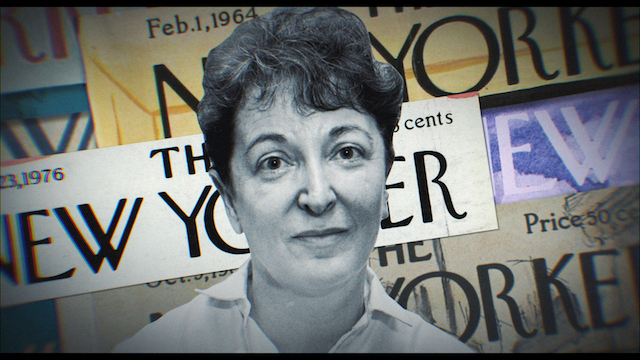

Pauline Kael was the most renowned film critic of the 20th century. It’s a strong statement, but inarguable: You may not have loved or agreed with or even respected Kael’s criticism, but you could not deny its robustness, passion, or significance. For Kael, movies were both high art and utterly relevant to our daily human existence; and movie reviews thus mattered accordingly.

What She Said, a new documentary about Kael’s work as a critic and cultural force, had its theatrical premiere at the Nuart Theater in Los Angeles on December 13 and will open at Film Forum in New York City on December 25. It was a pleasure to interview New York-based filmmaker Rob Garver about the film—what it is, what it isn’t, and, of course, “what she said.”

The Millions: Let’s start with the film’s title: In The Hollywood Reporter’s review, Todd McCarthy suggests that film criticism as an “art” (versus a “craft”) is up for debate. We learn in the film that Kael had originally hoped to be a playwright, but that she was rather bad at it. She also tried again to be involved in moviemaking later in her career, when she attempted to co-produce a film with Warren Beatty (she ultimately withdrew from the project). Tell us why you think Pauline Kael was an art maker.

Rob Garver: She was an artist because she had a gift and she cared enough to take it as far as she could go. Pauline was really not a film critic; she was a writer whose subject was the movies. She gave all of herself to it—all her knowledge, experience, and talent. Not to mention humor, wisdom, honesty. Even if you felt she was wrong about a movie, she was always enlightening—or funny, or maybe rude, or all three at once. And she believed that at his best, a critic could be an artist too. She wrote about that.

TM: I couldn’t help thinking of Susan Sontag: She too is better known for her criticism, while she aspired to be a great novelist, and also attempted to make a film (which was not well received). Both women were passionate about the art of filmmaking but had almost polar opposite tastes. (They also had a common nemesis in Normal Mailer!) To your knowledge did they ever encounter each other?

RG: They were both California girls—as was Joan Didion—but I don’t know if they ever spent any real time together. I believe I did find a note from Sontag to Pauline (as I did from Didion) in Pauline’s archives at the Lilly Library. A friendly note, about one of their books.

TM: How much time did you spend researching Kael’s archives, and what were some of the most engaging or surprising things you found there?

RG: One of the first things I did was to hire a great researcher named Rich Remsberg, and together we spent two weeks in the archives. One of the great things we found were the letters from celebrities, some of which made it into the film. Some that didn’t were a series of letters from the famous producer Ray Stark—about five or six letters written over a period of about 10 years. Funny and interesting because they were initially friendly, but then, over time, become more and more frustrated, because Pauline is obviously not giving his movies the love he feels they deserve.

The best part of her archives, though, are the many letters she wrote to a couple of her close friends when she was in her early 20s—as a college student at UC-Berkeley and then in New York after college. It’s Pauline at her most vulnerable and emotionally naked, and most intellectually voracious. She was interested in everything. She was a young person who very much knew herself, but who also struggled with acceptance I think, because of her strong opinions, even at that age. She also seems to have understood how the world worked already.

TM: You convened quite an all-star cast: Greil Marcus, Camille Paglia, Quentin Tarantino, Paul Schrader, David Edelstein, Joe Morgenstern, Alec Baldwin, David O. Russell, Sarah Jessica Parker as the voice of Pauline Kael, and others. Was there anyone you’d really hoped to include who refused or was otherwise unavailable? Did you consider enlisting today’s prominent critics (e.g. Manohla Dargis and A.O. Scott, David Denby and Anthony Lane), or younger critics? Do you think the new generation of filmmakers, actors, and critics know how central Kael was to film culture during her time?

RG: I would have loved to talk to Woody Allen and Warren Beatty, but I don’t think they wanted to talk to me. I tried. Spielberg I tried, DePalma I tried. David Lynch I tried. Armond White I tried. Michael Moore I tried (he can’t stand Pauline), Manohla Dargis declined, A.O. Scott didn’t respond (but he wrote a lovely obit in The New York Times when Pauline died). Denby I didn’t approach as I already had several critics, but they were friends, and I think they had a falling out. Some people just don’t like to go on camera, and I respect that.

Not sure about current critics knowing Pauline. Some do. Eric Kohn at IndieWire teaches a class in criticism at NYU, and Pauline is part of his lesson plan. Others have told me the same thing. But I think unless a critic is steeped in film history—and they should be—they don’t know her, or don’t know her well anyway. I think Pauline’s first five books are just fantastic, great reading for anybody, critic or not. But if you’re a critic who hasn’t read at least one or two of Pauline’s early books, I think you probably need to.

TM: In the film, Molly Haskell says about Kael, “No male critic had as much testosterone as Pauline.” Kael was notorious for championing violent films like Bonnie & Clyde, Scorsese’s early film Mean Streets, the films of Brian de Palma and Francis Ford Coppola, as well as sexually controversial films like Last Tango in Paris. She was a feminist by example—speaking her mind, pursuing her ambitions, never compromising in order to be “nice.” But I wonder how/if Kael would engage today’s feminisms and/or the #MeToo conversations. Any thoughts?

RG: You can never say for sure, but one thing about Pauline that seems to hold up pretty well: She didn’t like messages in movies, she didn’t belong to groups, and she was never called a word with an “ist” at the end. I think, yes, she was a feminist by example, but she wouldn’t like to be called one. She did it on her own, in her own way.

She also loved the bad boys—Sam Peckinpah and James Toback, the guys who often shot from the hip, even if people like Toback missed more than they hit, creatively.

As for #MeToo, it’s hard to guess. Toback made a fool of himself and got caught, and I think she would not be on his side in that case, despite her friendship with him. And Harvey Weinstein she might see as a clueless narcissist in the vein of some of our current leaders. Of course, she was a woman, and a very sensitive person, and probably one who in her personal life didn‘t take any shit from men. But I think she was more the aggressor in sex. She did not have many long romantic relationships with men, I don’t think, but most of her friends were men.

I could imagine/hear her often taking the side of the men in the #MeToo debate (she was supposedly a champion debater in high school). I can hear her telling women to wise up—that if a guy is telling you to come back to his hotel room to audition, it’s a bad idea! I can hear her saying that men are naturally predatory when it comes to women—so watch your back! I think she would probably be on the side of men more than women in some of these cases. That’s just my guess. I think she might be on Woody Allen’s side, since she knew him and he didn’t have a pattern as others did. But who knows? Mostly, she didn’t take sides in her life, publicly, on public issues. She does write about the rape in the movie Straw Dogs in an unusual way, expressing feelings of both eroticism and revulsion. That’s a great example of her honesty coming through. And I think if she wrote that review today, she might be plundered.

TM: I’ve read that your interest in making this film began with your own admiration for and enjoyment of Kael’s reviews. But the film doesn’t shy away from giving voice to her detractors, showing the ways in which her sharpness, at the height of her powers, could injure filmmakers and their careers—David Lean did not make a film for 14 years after being eviscerated by Kael both in a review and publicly at a luncheon—not to mention ruffle the feathers of mainstream moviegoers. Would you say that the central tension or conflict of Kael’s legacy is the question of motives?

RG: Not in my book. I know there are many who think she was out to “get” people, but if you read her books, which are made up of her published reviews and essays, they are almost entirely thoughtful, honest, insightful. Hardly ever personal, although she could go there. I think maybe a more central “tension” might be her “rightness” on some of the big movies of her era. Many still get upset about her review of their favorite movie from 40 or 50 years ago. That speaks to who she was, and the power of her pen. I don’t think anyone gets upset about Rex Reed’s review from 50 years ago, or even Vincent Canby’s review from 20 or 30 years ago.

TM: Her supporters describe her as courageous and generous, her enemies as cruel and narcissistic. Her own daughter, Gina James, spoke to what she believed made her mother tick: “She truly believed that what she did was for everyone else’s good, and that because she meant well she had no negative effects. This lack of introspection, self-awareness, restraint, or hesitation gave Pauline supreme freedom to speak up, to speak her mind, to find her honest voice.” Does the film lean one way or another on the question of Kael’s essential character?

RG: Oh I love Pauline, despite her flaws, because I’m similar to her in some ways. If I love a movie, I’m all in; if I don’t, it’s hard to accept that people don’t see what I see. I’d make a terrible critic. So I can see where she came from, and I can feel for her because I know it wasn’t easy for her. (She also said she couldn’t be friends with someone who disagreed with her on a movie.) She had to avoid people in restaurants, at parties, in the streets. A price she paid. And she was a very outgoing, generous, and magnanimous person. But, I think she believed she was right, always. She believed she knew best and that people should listen to her.

TM: Kael’s unapologetic subjectivity seems to be a point of controversy in any assessment of her criticism: She could forgive one film for the very same flaw that made her love another. She critiqued “auteurism” for its emphasis on the filmmaker’s mark, but then became enamored of de Palma and to some degree Godard. Where do you think we stand now on the spectrum of subjectivity and objectivity in film criticism? Is the “I” of the film critic anywhere near as present in today’s film criticism as it was in Kael’s work? If not, are we better for it or worse?

RG: More than critiquing auteurism in particular she critiqued “isms.” She critiqued belonging to a cabal of thought. She believed in coming to a movie—or a painting or a piece of music or a book or play—with everything you are, with all your experience, and being open to it, not simply looking at it through the lens of a theory. That’s what makes her so fun to read: her windows are open, not half-closed. And she was never “all in” for any one filmmaker. She liked some of DePalma, some of Altman, some of Scorsese. Her job was to criticize, not to be a fan.

I think film criticism is probably much more subjective overall now, partly due to Pauline’s influence, but mostly due to the digital age, where everyone can publish their opinions. Bloggers can be very personal in their “reviews,” and I think this has probably bled over to professional criticism.

TM: Bio-documentaries often explore an interesting or important figure beginning with their childhood and background. What She Said doesn’t linger much on Kael before she became a well-known critic—which is to say there doesn’t seem to be much interest in psychologizing her. Was this your preference/decision, or was it more your sense of what her preference would have been?

RG: That would have been a different movie, much more narrow, and specialized. I wanted to make a film that was an expression. Not an analysis or comparison, or an effort to figure out why she was who she was, and why she wrote those things. I mean, I do think some of that comes through, but I was more interested in showing her work, and how it became part of the culture. My film is just what the title says it is—it’s “what she said,” not “why she said.” I’d be very happy to watch that movie if someone else made it though.

I wasn’t making it for Pauline, or making as I thought she would like it. The movie is my impulses and expression. I guess I’m channeling her, but I’m doing it in a way that pleases me. I just wanted to make her come alive.

TM: Do you think or hope What She Said might bring renewed attention to some of the landmark and classic films of Kael’s time? I know for me, it made me want to rewatch Bonnie & Clyde and all of Altman’s and David Lean’s films, and to watch Christopher Strong and Casualties of War for the first time.

RG: That would be nice. There are so many remakes these days that if you’re really interested in movies, you should know where they came from. Pauline mentioned that a few times—that what seemed new to audiences didn’t seem new to her, partly because she was, one, so well read and knew the great literature before she ever started writing about movies, and, two, knew movies and had seen so much.

One of the many things I found in the research that I learned about Pauline was that she was a voracious reader who went through all the works of so many novelists and poets in her 20s—not just one book, but she would read everything by that author and then move on to another author—and it formed a bedrock for her writing about movies later on.

And it is very fun to watch a movie after reading one of her reviews. She wrote a great review of the Fellini movie Satyricon and wrote about how she thought Fellini was really the good Catholic school boy who loves sex and sin, but who feels guilty about it all at the end of the day. Funny, and she makes you see her view.

TM: This is your first feature film. Tell us a bit about your own career trajectory.

RG: Many false starts, and a lot of plugging away without results. I’ve made my own short films since I was a teenager, and have done other things to make a living—but always working on my own projects and trying to break through with one of them. Writing scripts, developing ideas. This is my first one to break through. I want to make a fiction film that I’ve been working on since before the Pauline movie, and I’m writing a second script that is an out-and-out comedy, which is what I like most.

TM: Any theories on why this one broke through?

RG: I always felt very strongly that this could be a special movie, and I felt completely driven to make it. And I love the movie. That’s probably why it broke through. But also because Pauline is such a compelling figure: complicated, strong, powerful, flawed, but without the brazenness of so many in the movie business. She was like a buddha, in a way, in her certainty. A buddha who loved to drink and smoke and swear and live like a bohemian.

TM: Was it important for you that the film have a theatrical release, given Kael’s strong attachment to seeing movies in theaters, with audiences?

RG: Definitely! That’s what I told my sales agent when they signed on—that I wanted to get a theatrical release because my movie is primarily a “theatrical” movie, in that I tried very hard to make it visual and cinematic. Also because it’s a movie that stirs up a lot of feelings and ideas, and so when people see it in a group, there is always a lot of conversation afterward. But now we’re set to open in 30-plus cities theatrically this winter in the U.S. and Canada, and in more markets internationally. So thank fully my wish came true.