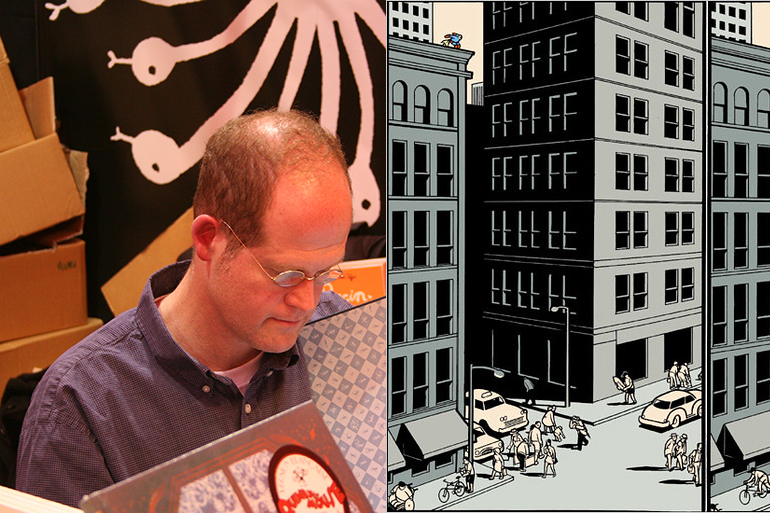

To read Chris Ware is to be struck by the joyous forms storytelling can take while being devastated by his characters’ personal tragedies. Ware’s vibrant experiments in layout and design—he often packages his graphic novels with oddities like flipbooks—are anchored by men and women hounded by loneliness, isolation, and a desire to escape their worlds, which are both cruel and mundane.

Such is the case with Rusty Brown, Ware’s latest work, nearly two decades in the making. The graphic novel follows the action-figure-obsessed titular character and his uncomfortable existence in the suburban Midwest, as well as two other characters: Rusty’s father, Woody; and Joanne Cole, a black language teacher.

Such is the case with Rusty Brown, Ware’s latest work, nearly two decades in the making. The graphic novel follows the action-figure-obsessed titular character and his uncomfortable existence in the suburban Midwest, as well as two other characters: Rusty’s father, Woody; and Joanne Cole, a black language teacher.

Though Ware began Rusty Brown nearly two decades ago, it’s still only halfway done; Pantheon published the first part in September. Already acclaimed for his seminal graphic novel Jimmy Corrigan when he started Rusty Brown, Ware has since written and illustrated Acme Novelty Library, Building Stories, his autobiography Monograph, and multiple New Yorker covers.

Though Ware began Rusty Brown nearly two decades ago, it’s still only halfway done; Pantheon published the first part in September. Already acclaimed for his seminal graphic novel Jimmy Corrigan when he started Rusty Brown, Ware has since written and illustrated Acme Novelty Library, Building Stories, his autobiography Monograph, and multiple New Yorker covers.

“I knew [Rusty Brown] was something I’d be working on for a long, embarrassing while—which is part of the ‘idea,’ insofar as there is one,” Ware says. “I know the book is exactly halfway done because it’s about six and a half people, and I’ve done three of them. Pretty straightforward, even if the book itself is a sprawling mess. But again, so is life.”

Emotionally and visually, Ware’s books are often sprawling and messy, but they are never unclear. His panels, small and detailed, are often part of meticulously designed pages, some of which unfold into larger configurations. And yet, there’s a spontaneity to Ware’s work. The narrative complexity of Rusty Brown, for instance, isn’t the product of a rigid outline.

“Like life, though I might have some sort of plan, I’m still essentially figuring it out as I go along,” Ware says. “I write with pictures, not words. And even if I did just sit staring at the wall thinking up a script that I’d later tediously illustrate, I’d still just be figuring it out as I went along, but I wouldn’t be doing it with images, and thus I’d be foregoing the peculiar aesthetic advantage that writing in comics uniquely affords.”

To work through a Chris Ware graphic novel is, in a way, to work through life—its joys, disappointments, exhilarations, and uncertainties. “I’m simply trying to get at that undercurrent of feeling that we call ‘life’ and that we do everything we can as adults to suppress—and don’t really sense except in moments of profound vulnerability and sadness,” Ware says, adding that he used to feel that way constantly as a child but now does only rarely. And he misses it. “I’ve long had the indescribable sense,” he says, “that my childhood and everything that’s ever happened to me is all still somewhere ‘right there’ but just slightly out of reach.”

This piece was produced in partnership with Publishers Weekly and the Texas Book Fair.

Image: Wikimedia Commons