As we careen toward the 2020s (!), and I personally careen toward my fifties (!), I have been increasingly experiencing what is probably a universal, and not entirely pleasant shock of aging, i.e., how fucking long ago in history the decade of my childhood exists. Specifically, the 1980s. I was born in 1975, but the ’80s marked the true memorable—in both senses—extent of those verdant years (not so verdant, actually, as most of them were spent in Saudi Arabia, but anyway). The 1980s long ago crossed that invisible cultural line into the realm of nostalgic camp: Pac-Man, early MTV, Arnold Schwarzenegger—even grainy TV footage of Ronald Reagan has long carried with it a kind of hideous sentimental aura. But enough time has passed and sociopolitical changes have occurred that it now exists as wholly in its own time as the ’40s and WWII did when I was a child.

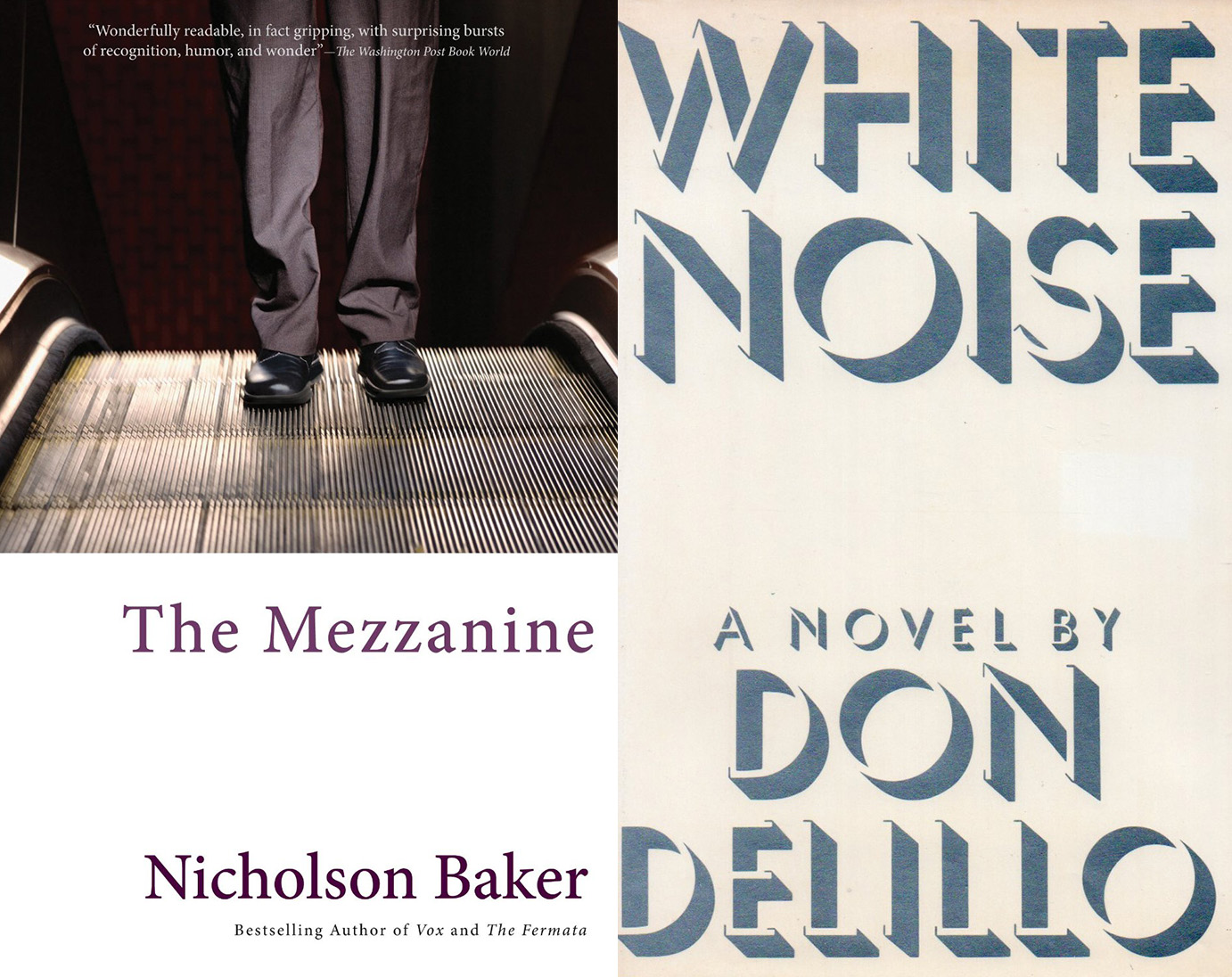

When this amount of time has passed, we can truly evaluate literature from an era, both in terms of how well it captures its own time, and how well it, however obliquely, anticipates or fails to anticipate ours. This seems a particularly pressing question during our current political and cultural insanity: Which books and authors are identifying something true about our moment, and in doing so, perhaps predicting something true about the next? Assuming the existence of readers 40 years from now, they will be able to judge our literature at more or less the vantage we can now judge that of the ’80s. Recently, I happened to reread two of the most-’80s of ’80s novels: Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine and Don DeLillo’s White Noise. It struck me what a contrast they provide—two ways of looking at what is now a startlingly previous age.

When this amount of time has passed, we can truly evaluate literature from an era, both in terms of how well it captures its own time, and how well it, however obliquely, anticipates or fails to anticipate ours. This seems a particularly pressing question during our current political and cultural insanity: Which books and authors are identifying something true about our moment, and in doing so, perhaps predicting something true about the next? Assuming the existence of readers 40 years from now, they will be able to judge our literature at more or less the vantage we can now judge that of the ’80s. Recently, I happened to reread two of the most-’80s of ’80s novels: Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine and Don DeLillo’s White Noise. It struck me what a contrast they provide—two ways of looking at what is now a startlingly previous age.

In The Mezzanine, Baker examines an 1980s office park under a scientist’s microscope. Nothing is too small to escape his notice, nothing too trivial to be beneath consideration: the superiority of paper towels to hand dryers; the overflowing multitudinousness of office supplies in cabinets; different vending machine mechanisms for dropping candy; the subtle kabuki of polite office conversations; the layout of a nearby CVS; an intricate, fantastic meditation on the similarities between office staplers, locomotives, and turntables. Applying a peeled eyeball to the overlooked mundana of office life, is, in fact, the aesthetic mission and basic point of the book. As it undertakes a seeming irrelevancy like tracing the evolution of stapler design from the early 20th century to the present, it invites a reader—unaccustomed to this level of granular detail applied to the banal—to ask what is relevant. Absent the large plot movements and rich character detail we’re accustomed to in fiction, what is left? Well, as it turns out, life, more or less. These tiny objects and customs constitute our lives—in the case of The Mezzanine, our lives as we lived them in the 1980s.

The narrator, Howie, is transfixed by the tiny ingenuities that populate the modern world, and by their evolutionary processes—both technical and cultural. Objects—and ways of using objects—have a lifespan as organic as the lifespans of the invisible humans who invent, market, and use them. The culture or character of any particular age is constituted by the stuff of that age and the way society agrees, by unconscious, collective fiat, to keep it or change it or discard it for something else, sometimes better and often worse. Throughout The Mezzanine, Howie’s little ecstasies about this type of staple remover, or that method of polishing an escalator railing, are tempered by a subtle awareness and anxiety about the loss of these inventions and learned behaviors to an ever-coarsening culture of pure productivity that doesn’t prize them (or anything much besides profit and cost-cutting).

The book is unostentatiously prescient on this point. At one point Howie wonders how all of this makes money, how it can last. As he says:

We came into work every day and were treated like popes—a new manila folder for every task; expensive courier services; taxi vouchers; trips to three-day fifteen-hundred-dollar conferences to keep us up to date in our fields; even the dinkiest chart or memo typed, Xeroxed, distributed, and filed; overhead transparencies to elevate the most casual meeting into something important and official; every trash can in the whole corporation, over ten thousand trash cans, emptied an fitted with a fresh bag every night; restrooms with at least one more sink than ever conceivably would be in use at any one time, ornamented with slabs of marble that would have done credit to the restrooms of the Vatican! What were we participating in here?

His thoughts go in this large, abstract direction as a natural extension of his noticing the very small, concrete things around the office. The sheer fact of the material world around him, all of the things that have to be manufactured and bought and cleaned and serviced to maintain the surface of a functioning 1980s office building, is both a delight and a bit of an existential horror at certain points. It feels—and, in fact, will turn out to be—unsustainable. Howie’s apprehension of the coming changes in the economy, the layoffs and downsizing both financial and spiritual that will render this kind of lavish and stable workplace antique, is a kind of involuntary thesis that follows unavoidably from his close reading of his world’s text. Nicholson Baker, via Howie, goes humbly about his quiet work, gathering data and making reasonable inferences about the world, inferences that have largely been borne out by the intervening decades.

In White Noise, Don DeLillo—in almost perfect contrast to Baker—looks at his world with the telescopic eye of a priest or pop-cultural anthropologist, beginning with a couple of large-scale hypotheses about modern culture and gathering particulars from there. Anyone familiar with DeLillo could more or less guess what these general hypotheses are, as they run throughout his body of work in various guises: 1) modern consumer culture is similar to primitive culture, and, related, 2) people want to be in cults.

As is standard operating procedure for DeLillo, the book, via its narrator Jack Gladney, operates in the oracular intellectual mode. There is, for instance, lots of stuff like this (during one of the many scenes in which Gladney watches one of his many children sleep):

I sat there watching her. Moments later, she spoke again. Distinct syllables this time, not some dreamy murmur—but a language quite of this world. I struggled to understand. I was convinced she was saying something, fitting together units of stable meaning. I watched her face, waited. Ten minutes passed. She uttered two clearly audible words, familiar and elusive at the same time, words that seemed to have a ritual meaning, part of a verbal spell of ecstatic chant.

Toyota Celica.

A long moment passed before I realized this was the name of an automobile. The truth only amazed me more. The utterance was beautiful and mysterious, gold-shot with looming wonder. It was like the name of an ancient power in the sky, tablet-carved in cuneiform…

Et cetera. If you’re not reading too closely, it sounds good, and the massed effect of paragraphs like this—of which there are many in White Noise—is to generate an impression of gnomic wisdom. But what is this actually saying? I suppose: brands infest our collective consciousness, more or less, though it sounds much more mystical than that. It’s never quite clear to me, reading DeLillo and especially White Noise, where the satire begins and ends. Is this supposed to be a parody of the pompous intellectual Jack Gladney, professor of Hitler Studies and wearer of a toga and sunglasses around campus? It would probably be more convincing as satire if it didn’t also sound exactly like Don DeLillo. And if there was much of anything else going on the book besides these sorts of ruminations.

Over and again, we learn versions of the same thing: car names are like magic words, shopping malls are like temples, the Airborne Toxic Event is like an ancient Viking Death Ship (to be fair, this is actually one of the more striking images in the book). This may or may not be true, but it isn’t especially illuminating on any level beyond the claim itself. The book, one feels—despite an established critical reputation for its prescience and incisive cultural vision—is not looking very hard at the things it purports to look hard at.

The result is a novel that misses many present or future aspects of Late Capitalism—Trumpism, economic inequity and class struggle, the Internet—and superficially identifies other burgeoning issues—environmental disasters, anti-depressants—without saying anything very noteworthy about them. White Noise’s mode of intellectual engagement is perfectly metaphorized by the Airborne Toxic Event—a large, dark cloud that floats above the pages and across the events of the narrative without bearing down on the characters or reader in any appreciable way, other than conveying ominousness.

DeLillo’s best book, Libra, operates in a mode much closer to The Mezzanine. Though it invokes its share of non-specific quasi-mystical dread, it is a piece of work grounded in the mundane facts of Lee Harvey Oswald’s life: the abortive time in the military; his awkward marriage to a Russian woman, Marina; the little firings and failures that pushed him, and the country, toward catastrophe. Even the larger circles of intrigue—the CIA and KGB and Mafia and the Cubans—are laboriously researched and rendered, and although a plausible conspiracy is offered, it is a conspiracy of error and stupidity and inertia, and convincing for that reason. Libra notices: it builds its case from the ground up, rather than a big top-down idea that must be proved—that perhaps only can be proved—by exhaustive and unilluminating iteration.

The difference between these novels says something important, I think, about the most fruitful way of looking at our present moment. There is, on Twitter and elsewhere, the constant search for the Big Idea, The Grand Unified Theory of Trump and Late Capitalism. In a media environment that almost exclusively rewards brevity and pithiness, memorable pronouncement is the coin of the realm. In this sense, DeLillo really was prescient—if nothing else, the style of White Noise fully anticipates our era, the superannuation of truth by the impression of truth, or just by sheer impression.

Still, the most important work will always be done on the ground level, with attentiveness to the little particularities. We are always too close to the big thing to see the big thing, and so writers are at best like the blind men surrounding the elephant of their particular era—here, a tail; there, a baffling trunk. The Jack Gladneys and their Big Ideas will not often provide a definitive record of their time, or a projection of the one to come. It will be constructed by the Howies, all the careful and conscientious noticers of the world.