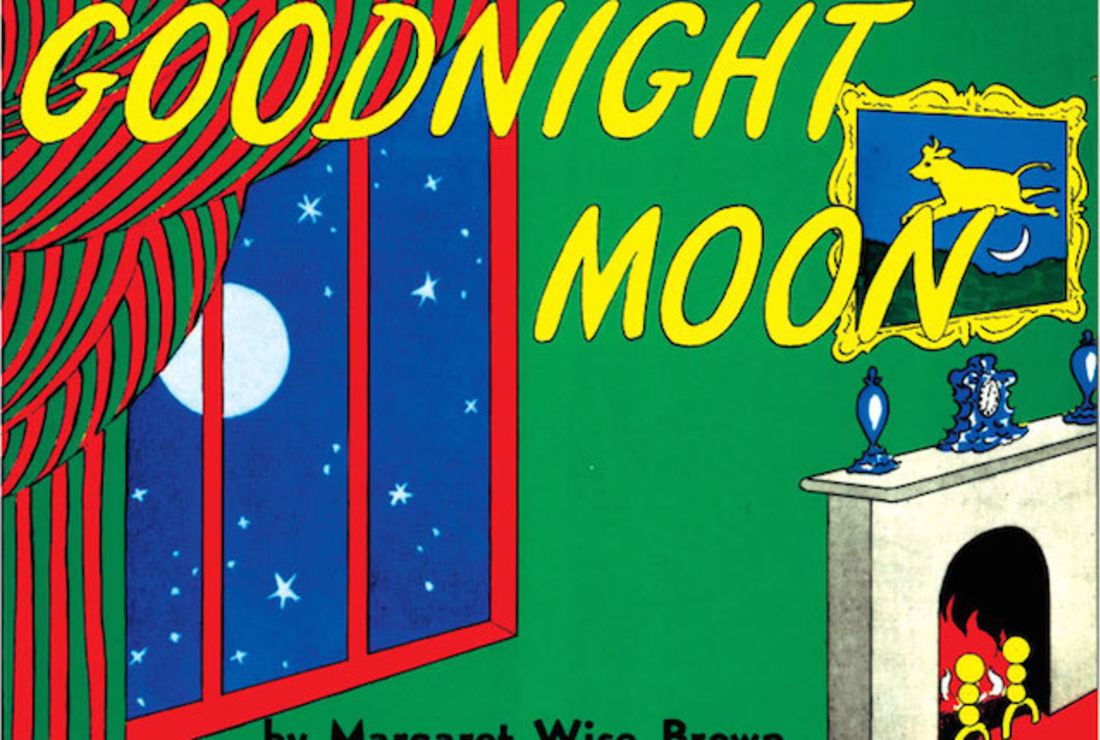

There’s no plot to Goodnight Moon, no characterization, no conflict. Every word written by Margaret Wise Brown and every detail illustrated by Clement Hurd is designed to build the illusion of comfort and stability—much in the same way that Star Wars presents a galaxy of infinite possibilities that includes one where your spaceship’s starter refuses to turn over, or the way that Harry Potter depicts a version of middle school where you are actually special.

In the case of Goodnight Moon, all the words and details—save one notable exception—work together to build Brown and Hurd’s fictional world. In the midst of the book’s mirrored repetition of household objects and animals, the goodnights to the clocks and socks, the kittens and mittens, is a white page with the words “Goodnight nobody” printed on it. It jolts the adult mind out of the trance the book’s murmured sibilants can produce. Goodnight nobody? What does that mean? Who’s nobody? Is children’s literature ur-cozy room haunted? This strange page feels like the point at which the book’s childhood materialism and chronic OCD list-making morph into existential despair (which makes Goodnight Moon the perfect bedtime story of grown-ups too).

But what the adult mind–especially one prone to the nagging-doubt-pre-sleep death spiral–reads as gloom is, in the context of Brown’s micro-fictional universe, just the introduction of the unknown. Worlds, even ones created for children’s bedtime stories, need a little mystery. In this case, not a mystery to solve, but one that remains unsolved; less whodunit and more who-or-what-is-it. For a fictional world to feel real, some part of the story has to reach outside the setting and break the seal of perfect self-containment. There are some characters we will never figure out. Some places we will never understand. Not everyone gets an arc. And sometimes loose ends work better when they are left untied. The least realistic fantasy is that in which everything is revealed, that in which everything adds up. No level of omniscience can answer every question that might occur to the reader. No author is the Laplace‘s Demon of her own creation.

But today, many authors and filmmakers seem convinced they really do know the location of every atom in their fictional universes. Instead of expanding their worlds, creators—and the executives pressuring them—exploit them. Characters and settings become resources to tap. The best and most interesting worlds are strip-mined, their forests clear-cut, their mountaintops blown clean off. If you’re successful, you’ll never run out of space that needs to be filled or money that needs to be made. Maximalism has nothing on serialism, the way the infinite cannot compare to the merely big. In other words: Once the mystery of Nobody is solved in the sequel to Goodnight Moon, readers can finally learn what kind of complex and fully-realized life the quiet old lady has once that bunny finally goes to sleep.

This is how minor characters in superhero movies come to have whole worlds built upon them. And each time this happens—every time an unnecessary backstory is explained—some part of the mysterious fictional world dies. These minor characters become load-bearing gargoyles, and their inability to support the weight of the story weakens the entire structure. Perhaps the greater Goodnight Moon universe will support a prequel explaining the deep backstory and life path of the quiet old lady and the personal meeting “hush” has for her. Or maybe that will be where the money and the interest dry up. If they ever do.

In addition to the degradation of fictional universes, this hyper world-building means we spend so much time in familiar (and ever-expanding) worlds that we don’t invest in new ones. Too many choices; let’s just watch something with superheroes in it again. The rules are familiar, and that familiarity creates the illusion of comfort and stability. Goodnight lightsabers. Goodnight wands. Goodnight Godzilla. Goodnight James Bond.

The creation of fictional worlds and universes is an achievement to be celebrated (and rewarded), but so, now, is their stewardship: knowing when to push further and what to leave unspoiled. Not every old lady needs a complex backstory, not every Nobody has to go off in the third act or the third film. Sometimes the mysteries in our fictional worlds can simply be put to bed.