At parties, people would ask Dexter Palmer, “What do you do?”

They’d ask the inevitable follow-up, “What are you working on?”

“Well, this book about a woman who gives birth to rabbits that’s based on a true story,” he’d say, which was the truth at the time.

Strangers weren’t quite sure what to make of that, so Palmer would talk about his research: lots of texts from the 18th century, including obsolete articles about women’s anatomy, or the history of the “royal touch”—the idea that kings could heal anyone’s ailments with a little bit of monarchical contact. In the context of Palmer’s library dives, the notion of a woman birthing rabbits didn’t sound so ridiculous.

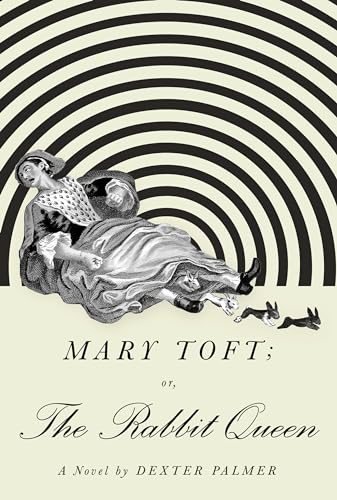

The book, Mary Toft; or, the Rabbit Queen, is Palmer’s third work of fiction and will be published by Pantheon in November. Its genesis goes back to 1996, when he was getting his PhD in English from Princeton University. In a class titled Representations of the Improbable, Palmer had to give a presentation on fraud. So he uncovered the story about the woman who claimed to give birth to rabbits and tried to understand the most obvious question: Why the hell did anyone believe her?

Over the course of two decades, Palmer returned to that idea. He kept clips of articles that were somewhat associated with the rabbit case and books about the 18th century, never sure what he would make of all this material, until it became the novel concept he sold to Pantheon and the recurring subject of polite cocktail conversation.

Palmer says that because he still lives in Princeton, N.J., a town of Ivy League academics, those same party guests often asked whether the book would include a bibliography—which would be unusual for a novel. Mary Toft does include a list of sources at the end, with Palmer’s caveat that he’d “taken a novelist’s liberties with its subject matter,” and following that, an itemization of those liberties. All his lies, basically. Palmer laughs when he tells me, “As an academic, there’s that bit of me that wants to prove that I did the work.”

The work is the research, but of course, it’s also the writing, which is getting easier for Palmer. Or at least, it’s getting faster. His first book, The Dream of Perpetual Motion (2010), which is like Kafka meets steampunk, took 14 years to finish. Version Control (2016) is a tome of speculative fiction that warps into a time-travel tale. That one took about five years of work (and a lot of cutting—40,000 words, a short novel’s worth). Mary Toft was done in just two years, written bit by bit after the workday and on the weekends.

The work is the research, but of course, it’s also the writing, which is getting easier for Palmer. Or at least, it’s getting faster. His first book, The Dream of Perpetual Motion (2010), which is like Kafka meets steampunk, took 14 years to finish. Version Control (2016) is a tome of speculative fiction that warps into a time-travel tale. That one took about five years of work (and a lot of cutting—40,000 words, a short novel’s worth). Mary Toft was done in just two years, written bit by bit after the workday and on the weekends.

Ask Palmer “what do you do?” somewhere other than a Princeton party and he’ll tell you about his day job: He works for the College Board, writing test questions for the SAT. He can’t talk much about the job itself—he signed an NDA—but he’s been on the test-writing circuit for the better part of 13 years, having also worked on the GRE and AP exams.

Palmer’s workdays are filled with a different kind of creative writing. Testing someone’s reading comprehension requires a mind-set that’s “precise and, at the same time, elliptical.” Good test-question writers need to figure out all the ways students might possibly misread a sentence. To write a good multiple-choice question, they have to write one correct answer and three plausibly wrong ones.

Is understanding how people might misinterpret something helpful when writing fiction? “It’s different, because if someone misreads a novel, it’s not really high stakes,” Palmer says. “The worst thing that’s going to happen is that someone posts a one-star review on Amazon or something like that.”

Which is to say, Palmer is okay with his writing being misunderstood—not a bad way to approach a novel about a big lie.

Mary Toft isn’t really about the character of Mary Toft. She gets two short chapters from her point of view, but the book is ultimately about the men who surround her who have all, for various reasons, taken on the curious case to understand what’s going on with the rabbits. It’s a conspiracy of self-delusion but also a tale of four dudes talking about a woman’s body.

It’s a tricky proposition: “Mary Toft has to be a book about women,” Palmer says. “But it also has to be a book about men talking about women.” Those men who populate the book, because of their status and because of their gender, become the arbiters of how Toft is perceived. It’s a book about what happens when we ignore expertise and decide to instead reinforce each other’s misthinking. “Why would a number of people, many of whom are very smart and educated, collude to believe a thing that seems self-evidently, materially false, to the point of being ridiculous?” Palmer asks.

In that way, Mary Toft gestures at our current political situation, in which a lot of reasonable people have decided to take at his word a president who is constantly lying. (Palmer began writing the book in 2016, naturally.) Trump is, after all, an authority figure—one of the highest in the world, depending on whom you ask.

Palmer says, “Expertise is why people feel obligated to go get vaccines, for example. Expertise tells us that the climate is changing. And yet, just because of the way the society is, who gets designated an expert is largely a class issue.”

When elites fancy themselves experts, isn’t it then subversive for the public to disown expertise and reclaim that power? The problem is that expertise is also often condescending, and it might behoove towns like Princeton to be more self-aware about that.

Modern education approaches pupils as blank slates who must be taught the right thing. But we live in the age of misinformation, of dishonesty, of YouTube—and students now come to class already believing all kinds of horrible things: the conspiracy theories of Alex Jones, the misogynistic views of Jordan Peterson, the conspiracy theories and misogynistic views of the president. The role of a teacher is no longer to teach but to first help a student unlearn. Disproving a lie in 2019—and in 1726—is more complicated than just pointing out that something is false. It’s even more difficult when a lot of people believe in the lie.

“People can collude in believing something,” Palmer says. “That is resistant to education.”

But this is not the lesson Palmer set out to teach readers when he first endeavored on Mary Toft. He started writing in spring 2016, when the moment was uncertain. “I can’t claim that I somehow foresaw our situation when I started to write about it,” he concedes.

Mary Toft really just started out as a book about a woman giving birth to rabbits. Like Palmer’s other two novels, the idea emerged as he was writing and researching. Palmer recalls something his editor told him once during a conference call: “Nobody ever writes an important book on purpose. It’s always by accident.”

This piece was produced in partnership with Publishers Weekly and also appeared on publishersweekly.com.