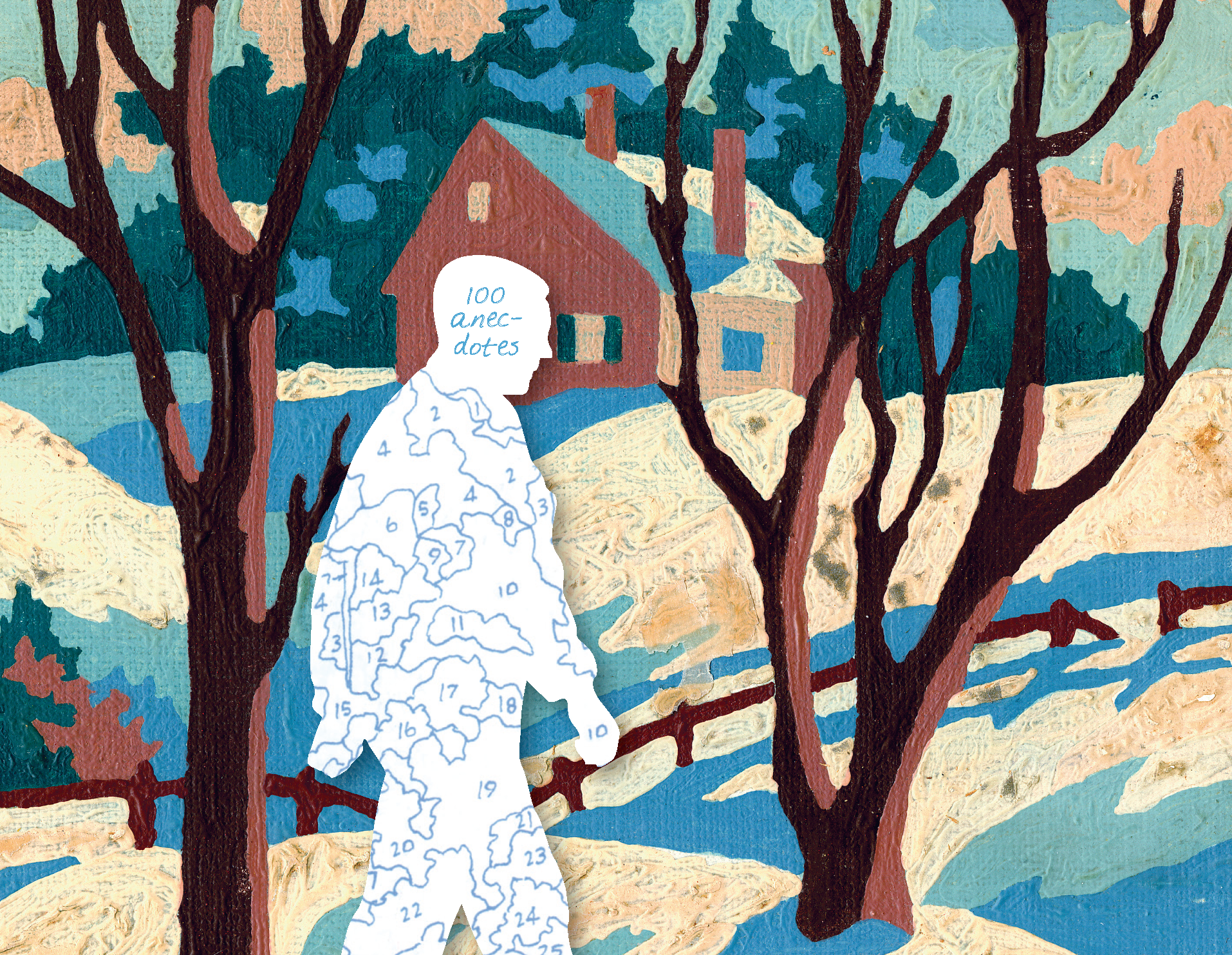

“Our town is famous for its deep, beautiful mountain gorges spanned by one-lane bridges, and it is from these bridges that local would-be suicides typically jump.” So begins “Copycats,” the sixth piece in J. Robert Lennon’s collection Pieces for the Left Hand: 100 Anecdotes, published by Graywolf Press in 2005. The swerve that occurs in this first sentence—we are lulled by tourism-brochure language only to be slapped by the word “suicides”—is a microcosm for the story, in which a college student’s painfully brief suicide note (“can’t/go on”) is revealed to have been torn from a larger, far less devastating note: “Midterms over, dude! I totally can’t/wait for this party. You can go on/without me if I’m late.—B.” The student’s “suicide” is now understood to have been an accidental death, a drunken fall to the bottom of a gorge, rather than an intentional act—but not before there have been “a rash of copycat suicides.” We move from the shock of the suicide, to the shock of the non-suicide, to the shock of the copycat suicides, all in the course of a page and a half. There’s plenty of horror in these shocks—and also some very black humor.

Pieces for the Left Hand is all about the swerve. In these hundred brief pieces (are they micro essays? Flash fictions? Prose poems? Who cares?), the assumptions set up at the beginning are overturned by the end. Every time I return to this book, I’m struck by Lennon’s ability to achieve this movement, and in so few words.

The swerve is used to different effects throughout the book. In “Twilight,” a coffee shop clerk is puzzled when some French tourists inquire: Where is twilight? The clerk politely explains that the end of the pier is the ideal place to view the sunset, only to realize that the tourists were seeking the toilet, not the twilight. Still, walking home from work, the clerk witnesses the tourists standing at the end of the pier.

The swerve here is not the whiplash of “Copycats,” but rather the pleasure of noticing, perhaps for the first time, that “toilet” and “twilight” are word-sisters; the universal humor of a linguistic misunderstanding; and the final beat, in which the awkwardness of the mistake has led to a moment of beauty unachievable but for the mistake. In a role it plays throughout the book, humor undercuts potential sentimentality.

Reading this book reminds me of running into a beloved and witty friend on the street, hearing their latest piece of bizarre gossip. Retelling these stories—which are not much longer in the summary than in the original—I feel the same charge I experience when some strange little thing happens to me, a coincidence or mix-up, that I’m eager to share with someone.

Yet it doesn’t do these pieces justice to dwell on their wry charm, for that trait is entwined with profound darkness, the ever-presence of death, a disconcerting eeriness that pulls back the veil on the illusions of daily life. In “Tea,” the narrator calculates the quantity of tea that his mother drank “in the twelve years between my father’s death and her own.” He concludes: 21,000 cups of tea, 1,300 gallons of tea, “a measure of loneliness.”

After I recommended Pieces for the Left Hand to a student of mine who often chafes at the contrivance of fictional narratives, he came to my office lit from within by the reading experience. Each of the stories, he said, has a perfect “it-ness” to it: it is what it is, no more and no less. Just the most efficient possible presentation of narrative.

I agree with my student; there is a straightforwardness to the delivery that plays potently against the many minor epiphanies in the book. At the same time, there’s a decided surreality to these stories: the narrator sees “giant yellow machines, bought by the city for the purpose of clearing wet leaves from the gutters” moving down the street with no drivers in them. In “Get Over It,” a town is in mourning for a fire that killed eleven children … forty years prior. These are the surrealities of life itself: surrealities created by dreams, by memory, by emotion.

Lennon elevates the mundane moments in life—or unveils their shadow side. These pieces deal in the minute instants when you mis-see, mis-hear, mis-interpret something. They point to the inherent absurdity of being a human moving through the world. I love the book for both its irony and its generosity.

I first read Pieces for the Left Hand over a decade ago, when I was making my own forays into narrative brevity. Weary after writing and then throwing out three full-length novels, I was craving—as a writer and as a reader—narratives that could be contained in one hand. Narratives that were more like doorways than like castles. Other books and writers helped me at that time: Jamaica Kincaid’s At the Bottom of the River, Bernard Cooper’s Maps to Anywhere, Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Mary Ruefle’s The Most of It, Jorge Luis Borges, Lydia Davis.

Pieces for the Left Hand, along with these others, served as a critical permission book. It raised questions for me: What constitutes a narrative arc? How concise can a story be? Does genre matter? How does it help—if at all—to label things?

These books emboldened me: A book can contain whatever it is that you need to say. It can take whatever form you want it to take. Evade definition, and you free yourself.

As I learned from Lennon’s “The Mary,” an arc can consist of a person walking past a statue of the Virgin Mary every day—only to realize that the holy statue is actually an umbrella that was closed for the winter.

With this in mind, I began what would later become my first published book, And Yet They Were Happy, comprised entirely of stories that are each precisely 340 words. Within that arbitrary numerical constraint, I allowed myself to experiment with many different sorts of arcs.

Pieces from Lennon’s book arise randomly in my mind, almost like memories from my own life. I’m thinking now of the one in which the narrator spies garbage trucks at night, sprinkling cinnamon on the streets rather than collecting trash. When I was having trouble locating this particular story amid the hundred anecdotes, I wrote to J. Robert Lennon, asking if he could remind me of its title.

He replied: “Ha! No, I don’t think that’s me, actually, though it easily could be.”

Our exchange—and my surreal misremembering—made me feel like a character in Pieces for the Left Hand.

I could have sworn that story existed in the book. But maybe better yet that the book created enough space for the story to exist in me.

This piece was produced in partnership with Publishers Weekly and also appeared on publishersweekly.com.