In her five books of poetry, Toi Derricotte has joined a generation of writers who have picked up the mantle of the confessional poet, seeking to blend personal experience with larger questions around race, gender, sex and identity. There is a specificity and an unflinching candor that runs through Derricotte’s work, incisive and unsparing toward everything and everyone—especially herself. This could seem cruel, but it’s tempered by what I called, in our conversation, a spiritual quality—she uses her poems to understand herself and to be understood by others, viewing self-knowledge and communication as vital, life-affirming acts.

Derricotte has received many award—including the PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry in 2012 and three Pushcart Prizes—and is a Professor Emerita at the University of Pittsburgh. Derricotte is also the co-founder of Cave Canem, which has become one of the nation’s great literary organizations, receiving the Literian Award for Outstanding Service to the American Literary Community in 2016 by the National Book Award Foundation.

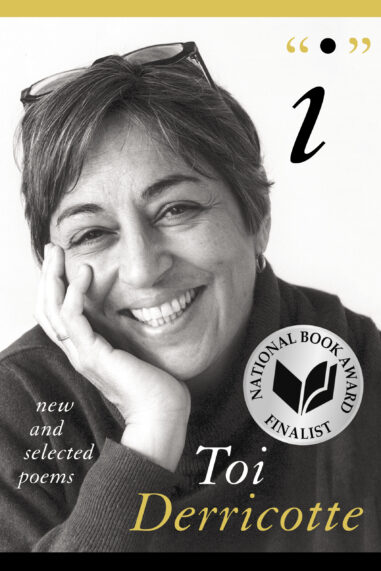

Derricotte’s new book is “I”: New and Selected Poems. We spoke recently about her work, career, and being hopeful at this moment.

The Millions: What was it like to assemble a new and selected volume of your poetry? Because this is your chance to define yourself and your work.

Toi Derricotte: My editor suggested I do a new and collected. When I started putting the book together I realized that it was an opportunity to think about all of my work as one long project. I have always thought of every book as its own project. How many writers get to look at 50 years of their writing in one book? I think that’s rare and I feel really good about it.

TM: You open the book with a quotation from Czeslaw Milosz: “The purpose of poetry is to remind us / how difficult it is to remain just one person.” I keep thinking about how much of your work has this almost spiritual element, interrogating your own life because you are seeking to understand and be understood and through that to find connection with others.

TD: I didn’t used to call my writing process “spiritual.” I don’t know what I called it. I thought of it as purely artistic. I knew that in my life I didn’t want to do harm to others the way I had experienced harm in my childhood. I wanted to find ways to be myself and to express myself without harming people. Putting difficult feelings into poems seemed a perfect way to do that. My mother was not happy about a lot of my work because I said things about my childhood that she considered to be untrue. She actually had a totally different memory of my childhood than I did. She didn’t believe she or my father had done physical or psychological damage to me, so in that way my writing opposed her belief and did harm to her. It’s difficult to sort out your truth from others’ truths, especially if your truth is not a truth that makes the ones you love comfortable. I grew up with a violent father and I had to be silent about my feelings. I had to figure out how to have power and how to express that power—and even figure out what power is, a different power than the one used against me as a child. As a black woman, there are so many layers to figure out—not only who you are and how you can be yourself in a racist world, but what is a self that is your own and not a response to someone else’s idea. It’s been a long journey. Now I think that journey has been about connecting to a deeper power, which is, I guess, what I would call a spiritual power.

TM: As you were talking about violence—I’m not religious though I was raised in the church—I was reminded of a quotation about hell being the absence of God.

TD: It’s funny you should say that because early on, that’s the way I was taught to believe in hell. In Catholic school we were taught that hell is a place in which you are out of communication with God forever, isolated from God. The most terrifying idea for me is to be someplace where I can’t be in touch with what I feel is the most beautiful and powerful part of myself, which is the way I think of God. Maybe that’s what depression felt like for me, being out of touch with the most beloved part of myself. Now I don’t think of God as something out there that I pray to. I think of God as working through me, and as a part of all of us. So yes, that belief is deeply at the root of my need to express myself and to be connected to others.

TM: I remember your poem “Speculations about ‘I’” when it was published a few years ago. Why did you decide to call the book I?

TD: My son came up with the name. I was going to call it Speculations about I and he said, mom, that’s boring, you should just call it I. Recently I have been thinking about how all of our life we’re in communication with our teachers—and we’re still learning from them, and arguing with them, too. In the book, I mentioned some of my teachers—Ruth Stone, Audre Lorde, Lucille Clifton, and Galway Kinnell—but one of my teachers was M.L. Rosenthal. When I was in his graduate class at NYU in the late ’70s, we never read a woman writer in his class on Modern American Poetry. I remember questioning him, “Why aren’t we reading any women writers?” He said, condescendingly, one day, “We’re going to read Sylvia Plath because Toi has brought this up as something we must do.” Then he gave this brilliant talk about Plath’s work. He was the one who coined the term “confessional” about the work of Sylvia Plath, Lowell, and Sexton. He was a great critic at the time and when he used the word “confessional,” he meant it pejoratively. I think autobiographical writing has always had that tinge of, “Oh it’s just people talking about their feelings.” The poem “Speculations about ‘I’” was written 40 years later. In a way it is an argument with M.L. Rosenthal, but really it’s my defense of myself to myself because all along I was my own worst critic.

TM: What’s the earliest poem in the book?

TD: Probably “the mirror poems.” Those poems happened at the same time I started writing The Black Notebooks. I was in a suicidal depression, the worst one of my life, after my husband, son, and I had moved into an all-white area 10 miles from New York City, Upper Montclair, N.J.. We were the first black family. Three months after we moved in I remember just sitting at the dining room table scribbling on a piece of paper. Just recently I found that piece of paper. I had scribbled, “The Black Notebooks,” which was the beginning of the book I didn’t finish until almost 30 years later. “The mirror poems” happened just as I was coming out of that depression. They’re such strange poems. They’re not autobiographical. In some ways I think they mirror the voice in “Speculations about ‘I.’” They kind of bookend each other. In both poems there is an external voice, as if it’s not the person, but a voice from somewhere else, a kind of mirror voice that is speaking about the person writing.

TD: Probably “the mirror poems.” Those poems happened at the same time I started writing The Black Notebooks. I was in a suicidal depression, the worst one of my life, after my husband, son, and I had moved into an all-white area 10 miles from New York City, Upper Montclair, N.J.. We were the first black family. Three months after we moved in I remember just sitting at the dining room table scribbling on a piece of paper. Just recently I found that piece of paper. I had scribbled, “The Black Notebooks,” which was the beginning of the book I didn’t finish until almost 30 years later. “The mirror poems” happened just as I was coming out of that depression. They’re such strange poems. They’re not autobiographical. In some ways I think they mirror the voice in “Speculations about ‘I.’” They kind of bookend each other. In both poems there is an external voice, as if it’s not the person, but a voice from somewhere else, a kind of mirror voice that is speaking about the person writing.

TM: The Black Notebooks is a truly great portrait of depression and the way you wrote about your illness and self-loathing really resonated with me and has stuck with me over the years.

TD: I’ve heard that from a lot of people. But of course I hope it’s much more than a book about depression. I meant it to interrogate aspects of the self through the lens of race. In my interactions with people, because of my light skin, I’m not recognized as black, so there is a lot of emphasis in that book on the dangers and internal conflicts around visibility and invisibility.

How do you come out of silence, which is so terrifying, and make a real connection unless you face the thing that makes you most fearful? For me, it was rejection, by isolation and alienation from my “family,” from my deepest roots, from other black people. As a matter of fact, when that book was published I got a phone call from a man at the Black Caucus of the American Library Association who told me that The Black Notebooks had just won the award for the book of the year. I said, “No, it didn’t.” [Laughs.] He said, “Yes, it did.” I said, “No, it didn’t.” I had prepared myself for the worst thing I could imagine: to be hated by the people that I most wanted to be accepted by, to be hated for having conflicted feelings about being visible as a black person. It was a great gift. I realize now that it was a message from the universe that I was on the right track: that being vulnerable, telling the truth about myself was helpful to others.

TM: There are many reasons why I can’t imagine what it was like to be at NYU back then, but you also came up at a time when Plath and Lowell had done important work, but they were also dismissed, and they had difficult lives. It feels like it was harder to have a model about how to write and live.

TD: Every writer has to speak for the time. The important work that Lowell and Plath were doing was breaking open some things that were stuck. Certainly ideas about what it was to be a woman. Plath didn’t have a community in which she was accepted and understood. I think that was a big problem. Lowell was stuck in this weird aristocracy, but he was also mentally ill. They were doing very important work as poets and I identified with that work. I too wanted to write about parts of my experience that were damaging. When I was looking for a community for support, for other writers I could identify with, I found myself among feminist and lesbian women writers, Adrienne Rich and Audre Lorde, where I felt safe to explore aspects of my life that weren’t “pretty.” In some ways I think I was afraid that some of the poets I admired in the Black Arts Movement would feel that my poems betrayed blackness, because I talked about internal doubt and problems. Over the years, I have not found that to be the case. I have been loved and supported by many writers who were major poets within the Black Arts Movement. My advice to a new writer is go where you need to go to get the support you need to write. You have to find the cracks where you can get a little juice and live on that.

TM: I was thinking about that, in part, because one of your newer poems is “As my writing changes I think with sorrow of those who couldn’t change.”

TD: That’s so true. That’s what can happen, I think, with success, you’re appreciated for a certain kind of work and you get stuck; you’re afraid to change. It’s scary to change. That could happen to me. I don’t know. Success is hard for a writer.

TM: Has how you write changed over time?

TD: It’s certainly easier for me now. Every book is formally very different. I’ve always had to find a formal way to handle the new material I needed to write about. Bringing content and form together has meant that every book looks different—and I can see that in the new and collected—because the content is always different. I had to find ways to formally express that difference, though I always felt at war with form. I saw form as an expression of the dangerous aesthetics that had demeaned and excluded black poets. I had to find ways to both contain the poem and, at the same time, explode form. I think it was good because it produced the tension that holds the poems together; but I don’t feel that same tension in my writing now. I feel like the work just flows from a place that feels more me, me in a bigger way. I don’t know. I just feel more in the center and in control right now.

TM: I wanted to close by asking about Cave Canem, whose motto is “a home for black poetry.” I feel like almost every African-American poet I know or have interviewed has some relationship to Cave Canem. I interviewed Kwame Dawes a few years ago and he said something that I feel like you can relate to, “We are not inventing a community. What we are doing, though, is adding to the community’s ability to communicate.”

TD: Yes, it’s all of these places where energy is being connected. Cave Canem starts each year with the opening circle. All 50 or so fellows, faculty, and staff sit around in a circle on opening night and talk. There are so many things that happen at Cave Canem, and not because Cornelius Eady and I sat down and thought, we want this. I’m not saying we didn’t have a plan or we didn’t work for it, but a lot of things happened just as a result of us figuring things out in the moment. Like, the first night of Cave Canem, I’m not sure why we moved the chairs into a circle. I remember the room being set up in a traditional way with all the chairs facing the front. I’d been working in the Poets-in-the-School program for 20 years and I always had the teachers arrange the chairs in a circle and I knew the advantage of this. It’s not that it was an accident that the chairs were set up in a circle at Cave Canem, but the way that happened is like so many things that are central to why Cave Canem works. The idea of a circle is that there’s no real leader and everybody’s an equal part of the way we’re all connected.

I think it’s an expression of something bigger too. This is a hard thing to talk about, but I visited a lot of white homes when I was a child. I could visit white homes because I think the white parents didn’t know I was black, and so I had a few white playmates that I’d leave Conant Gardens to go and visit. Both blacks and white weren’t supposed to cross the dividing line. Our parents said that cars would hit us if we crossed Ryan Road, which was a busy street, but I think we all knew that the real reason was the dividing line between whites and blacks. However, the black people in my neighborhood didn’t stop me and I was curious. This was in the days when kids just went out and played. They weren’t watched that much. I’d go to the visit white friends, but I never wanted to be white. There was something that I did not feel was happening over there that was happening in my neighborhood, and among my own people. It’s true it was terrible in my home, much sadness, anger, and depression, but there was also vitality and joy and love. I have no idea where it comes from or why it’s there, but I think it’s a way of connecting. I think the power of Cave Canem is in the ways of connecting that are becoming more and more available now. It’s like coming home and finding all of the people we were separated from in the Diaspora. It’s like heaven.

TM: I think it’s impossible to talk about 21st-century American poetry without talking about the people who have been a part of Cave Canem: Tracy K. Smith and Terrance Hayes and Patricia Smith and Major Jackson and Elizabeth Alexander and Claudia Rankine and Natasha Trethewey and Yusef Komunyakaa and others.

TD: That is really, really true. Of course Cornelius and I did not have this in mind when Cave Canem began.

TM: So, you did not intend to transform American literature? I’m making a note of that for the record.

TD: [Laughs.] We were hoping to make it from one day to the next! But I do remember when we started saying things like, “That guy will be getting the Pulitzer Prize.” We started thinking this way probably six or seven years into it. But we knew it was a powerful thing on the very first night. It was beyond anything we could have imagined. From the first night, we knew how powerful it was.

You and I talked about spirituality. Some people don’t want to use this word but I really see Cave Canem as evidence of something at work beyond us. We had a closing circle at our first retreat and I remember this huge gold moon shining over us. I really felt it was the universe saying, “This is your time.” It’s our time. It’s something to do with change—with changing literature and maybe changing the way we see our country, and even the world. Tracy K. Smith organized an event at Princeton a couple months ago, a coming together of African-American poets and scholars, and it was wonderful. People were saying, “Is it possible to think that poetry can change the world? Can poetry make change happen?” People are starting to ask this. Not saying that poetry makes nothing happen, as the line in Auden’s poem suggests, but that poetry can make something big happen. This is a fragile, scary, but actual thought being spoken.