1.

As her native Yugoslovia became embroiled in war in the early 1990s, Dubravka Ugrešić left. She thought she was leaving for a short time—just a brief visit to Amsterdam. She wound up staying away longer than she planned, as she writes in the opening pages of American Fictionary: “Every day I would set off for the station and then postpone my return to Zagreb with the firm intention of leaving the next day…And then I suddenly decided I would not go back.” Ugrešić remained in Amsterdam until the time came for her to travel to Middletown, Connecticut, for a guest lectureship at Wesleyan University. She would eventually return to her homeland a year or so later, but only briefly, eventually being forced into exile in Amsterdam for her anti-war and anti-nationalist stances.

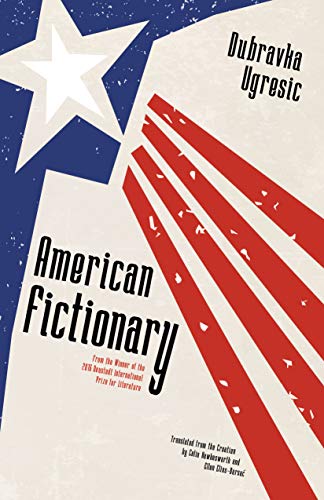

American Fictionary, out last year from Open Letter in an excellent updated translation by Ellen Elias-Bursać, is a collection of essays written while Ugrešić lived in Middletown. The brief pieces run the gamut of topics, from the American obsession with the organizer, to what it means to be an Eastern European Writer, to the mythical image America has of itself, even to a diatribe against the muffin (“A muffin is an infantile form of mush, a hodge-podge, the muffin is a treat for the poor and the amateur, the muffin is not just simple, it’s crude”).

Ugrešić writes as a poignant critic of American consumerism, of American individualism, and of the American pursuit of perfection. She sees in American cultural obsessions a commitment to the pursuit of tidiness. Though she recognizes an absence in her American subjects—“No American with a smidgen of self-respect knows who he or she is: that’s why every American has a shrink”—she keenly observes that they do everything in their power to mask it. We Americans hide our chaos in our organizers. “Chaos is divvied up into little piles, stowed away in shiny plastic compartments and closed with a zip-lock. Zip! There. No more chaos. No more darkness.” She longs to do the same with her own personal wreckage:

I don’t know where my former home is or where my future home will be, I don’t know whether I have a roof over my head, I don’t know what to think of my childhood, my origins, my languages. What about my Croatian, my Serbian, my Slovene, my Macedonian? What about the hammer and the sickle, my old coat of arms and my new one, or the yellow star? What to do with the dead, with the living, with the past or the future. I’m walking, talking chaos. This is why I buy organizers.

This sense of a lost home, and the disorientation Ugrešić experiences in its wake, is at the heart of her work. Reading American Fictionary with some knowledge of what’s to come for Ugrešić is harrowing—the return home that Ugrešić occasionally anticipates in these essays will not come to fruition; her homeland will not take her back.

“I shudder at my homeland,” she writes in “Life Vest,” the last original piece in the book, written as she finally flies toward Zagreb. “I shudder at the thought of the new country where I’ll be a stranger, whose citizenship I have yet to apply for, I’ll have to prove I was born there, though I was, that I speak its language, though it is my mother tongue.” Ugrešić imagines a certain kind of homelessness—one in which, though living in her native place, she has to go through the motions of acquiring legitimate legal residence. What she ended up with was exile. As she writes in “P.S.,” her addendum to American Fictionary included in Open Letter’s new edition, “I imagined that my work on the essays for my American fictionary would be my way of sketching my homeward trajectory. Soon enough the opposite proved true: the essays were, instead, an introduction to a different sort of fictionary, to the exile on which I embarked in 1993, only a year after I’d returned from America.” Ugrešić has been based in Amsterdam ever since.

2.

There’s a passage in Fox, another recent work of Ugrešić’s published by Open Letter (and translated by Ellen Elias-Bursać and David Williams), that suggests how Ugrešić might conceptualize the idea of home today. In the passage, an anonymous reader bequeaths the narrator, who closely resembles Ugrešić, a home in Kuruzovac, a remote town in Croatia. The gesture is rife with symbolism, of course, in part suggesting that insofar as Ugrešić has found a home to replace the one she lost, she’s found it in her global community of readers.

The narrator spends several idyllic days in the home in Kuruzovac, days that include a brief love affair with a mine remover who was squatting in the home when she arrived. The landscape of the region, the purple lilacs that abound, prompt memories of her childhood, of how, “when we were little girls, we carried flowers around in the thumb crease, holding our hands out before us like tiny trays bearing crystal goblets.” The morning after she arrives at the home, she goes out to the porch: “The air was redolent of lilacs. Down the steps I went and picked a lilac cluster. Back on the porch, I sat on the bench, broke off a tiny goblet-like floret, and poked it into the crease alongside my thumb. I sat there, thumb out before me, elbow propped on knee, taking care that the floret didn’t tip over—and breathed in the new morning. I cannot remember a morning that seemed newer.” The passage seems to harken to this one from American Fictionary, where Ugrešić recounts a stay at an inn in Norman, Oklahoma:

The narrator spends several idyllic days in the home in Kuruzovac, days that include a brief love affair with a mine remover who was squatting in the home when she arrived. The landscape of the region, the purple lilacs that abound, prompt memories of her childhood, of how, “when we were little girls, we carried flowers around in the thumb crease, holding our hands out before us like tiny trays bearing crystal goblets.” The morning after she arrives at the home, she goes out to the porch: “The air was redolent of lilacs. Down the steps I went and picked a lilac cluster. Back on the porch, I sat on the bench, broke off a tiny goblet-like floret, and poked it into the crease alongside my thumb. I sat there, thumb out before me, elbow propped on knee, taking care that the floret didn’t tip over—and breathed in the new morning. I cannot remember a morning that seemed newer.” The passage seems to harken to this one from American Fictionary, where Ugrešić recounts a stay at an inn in Norman, Oklahoma:

When I came out in my pajamas one early October morning onto the veranda, I sat on the porch swing and sipped at my warm coffee…the wail of a train’s whistle cut through the stillness, a sound I hadn’t heard since my childhood. This was an auditory reminder that trains passed through the town but didn’t stop. Enchanted by the air, as sweet and fragrant as an overripe melon, I felt as if here, on this porch…I could stay forever. That veranda is my “homeland.”

Similarities abound between these two depictions of a homeland—home is found in a middle-of-nowhere place, away from the forces of power and war that might like to force her out; the feeling of having found some sort of home comes on the heels of recollections from her childhood, perhaps the only time when she felt she truly had a home. As Fox’s narrator leaves Kuruzovac, though, the reality of what home has become in her life reemerges, and she faces the true nature of her world: “The world is a minefield and that’s the only home there is. I must accustom myself to this fact.”

I feel melancholy when I read Ugrešić—for the ways in which she calls out the foolishness of American culture and what we choose to value (observations as sharp today as they were some 25 years ago), and for seeing what was lost for her and so many others divorced from their homeland. There’s a palpable sorrow in her writing, culminating in moments where the wound feels especially raw. “At the end of every year I secretly wish for all my friends and acquaintances to live at last in peace with themselves.” Reading these essays, I find myself wishing that for Ugrešić—that she might find herself calmly reclining on that verandah in Norman, Oklahoma, at some version of peace with herself.