1.

In the fall of 2018, I travelled to Fayetteville to attend the second-ever Frank Stanford Literary Festival, held in honor of a wild, Arkansas poet who’s been dead 40 years. The only other time I’d visited Fayetteville was 10 years earlier when I’d attended the first-ever Frank Stanford Literary Festival. At that time, almost all Frank Stanford’s work was out of print. He was known only to a handful of writers and artists who kept his work alive by word-of-mouth and by posting some of it on the internet. The dedication of this handful, however, is hard to overstate. The 75 of us who attended came from all over the country. We stayed up all night in the Walker Community Room of the Fayetteville Public Library mixing whiskey and coffee, reading Stanford’s poems, and discussing the excesses of his life.

While many people still have not heard of Frank Stanford, he is more easily discoverable now. The enthusiasm of the first festival helped bring his poems back into print. Any bookstore with a decent poetry section should have one of his books—most likely What About This, the nearly 800-page collected works issued by Copper Canyon Press in 2015, and possibly Hidden Water, a collection of Stanford’s notes and letters published by Third Man Books, which is an offshoot of Jack White’s—formerly of The White Stripes—Third Man Records.

While many people still have not heard of Frank Stanford, he is more easily discoverable now. The enthusiasm of the first festival helped bring his poems back into print. Any bookstore with a decent poetry section should have one of his books—most likely What About This, the nearly 800-page collected works issued by Copper Canyon Press in 2015, and possibly Hidden Water, a collection of Stanford’s notes and letters published by Third Man Books, which is an offshoot of Jack White’s—formerly of The White Stripes—Third Man Records.

When I learned there would be a second Frank Stanford Literary Festival, I knew immediately I wanted to go back—this time not only to celebrate Frank Stanford, but also to gauge how the reception of his work has changed, and how times have changed.

If this is the first you’ve heard of Frank Stanford, imagine a rockstar, charismatic and tortured like Kurt Cobain, who happens to be a poet. Though largely unfamiliar to people outside the poetry world, Stanford is arguably the cult-hero of American poetry. In the four decades since his death, the lengths fans will go to read more, and learn more—not to mention the duty they feel to share him with others—continually renews his intrigue. Reading Stanford’s poems has caused people I’ve met to postpone graduate school to drive around Arkansas tracking down Stanford’s childhood teachers, and to propose marriage while staying in a hotel where Stanford once lived, and even to drive out to Subiaco Academy and sleep on the poet’s grave.

In part this is because Stanford’s biography reads more like a Southern myth than an actual life: He was born at the Emery Memorial Home for Unwed Mothers in Richton, Mississippi, in 1948 and adopted the next day by Dorothy Gildart, who raised him to believe he was descended from Southern gentry. When Frank was three, Dorothy married Albert Stanford, a successful civil engineer, who gave him his last name. Their union provided Frank a well-to-do upbringing in which he was often chauffeured in the family’s black Cadillac—an orphan and an aristocrat at once.

Seemingly, the person most aware of his myth-rich origins was Stanford himself. Though he’d intuited it earlier, he was 20 in 1968 when Dorothy admitted she’d adopted him. By then Emery Memorial had burned, along with its records, cancelling any hope Stanford had of finding his birth parents.

In light of his adoption, and perhaps noticing his slightly darker complexion and dark curly hair, he began to suspect he was of mixed race. People who knew him suggest how troubling this was for him, in the Arkansas of the late 1960s, to question his whiteness given the overt messages of white supremacy he’d received throughout childhood—and that he later disavowed. Even so, his friends and relatives agree: The revelation of his adoption shattered him. But while depression overtook him, his friends also remember him joking he could now invent himself however he wanted.

In his poetry, Stanford’s capacity for creative self-invention was seemingly limitless: Between 1971 and 1978 he published seven books of poems. The poet Lorenzo Thomas dubbed Stanford “The Swamprat Rimbaud.” Allen Ginsberg, when he stopped through Fayetteville in the early ’70s, wanted to hang out with Stanford when Stanford, already an acclaimed poet, was still an undergraduate at University of Arkansas.

With Ginsberg as his guest, Stanford invited Fayetteville’s literati over for a party in which he fired a shotgun through the ceiling in order to separate the real poets from the pretenders. After the pretenders fled, Stanford and Ginsberg, along with a few others, partied all night. This is according to Stanford’s friend Bill Willett, who was there, and who stayed, and who was tripping on mushrooms at the time.

Stanford’s poems were as wild as his life, and an overt aim of his poetry was to blur the two. This trait he shares with Bob Dylan. Like Dylan’s, Stanford’s origin-story becomes overtly mythic in lines such as: “I sing my flood song / I know my birth is a storm myth.”

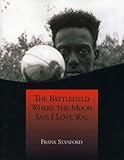

Stanford’s most ambitious book, the one that places him in conversations with other visionary, outsider artists such as Henry Darger, is entitled, The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You. The book is a 15,283-line epic poem of the Mississippi Delta told by a 12-year-old protagonist named Francis Gildart—a redneck Odysseus and poetic stand-in for Stanford himself. Stanford began composing this epic when barely a teenager. He published it in 1977 at age 28, the year before his suicide.

Stanford’s most ambitious book, the one that places him in conversations with other visionary, outsider artists such as Henry Darger, is entitled, The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You. The book is a 15,283-line epic poem of the Mississippi Delta told by a 12-year-old protagonist named Francis Gildart—a redneck Odysseus and poetic stand-in for Stanford himself. Stanford began composing this epic when barely a teenager. He published it in 1977 at age 28, the year before his suicide.

Here is one of Battlefield’s most often-quoted passages:

I think life is a dream

and what you dream I live

because none of you know what you want follow me

because I’m not going anywhere

I’ll just bleed so the stars can have something dark to shine in

look at my legs I am the Nijinsky of dreams

This short passage works not only to mythologize Stanford’s life, it also pulls the reader into that mythology: “what you dream I live.” Stanford’s early death, and the extraordinary details of his life, function to keep readers in the dream—incompleteness opening an evocative space for our imaginations. In the mid-2000s when I first read Stanford’s poems, I wondered if I’d come across an elaborate hoax. How else to explain my feeling that Huckleberry Finn himself had turned up in the ’70s in the Ozarks with a voice big and smart enough to sing about the South’s history, mystery, and trouble all at once?

In 1978 Stanford shot himself three times in the heart. His suicide occurred on the same day he returned to Fayetteville from New Orleans and found his wife, the painter Ginny Crouch, and his mistress, the poet C. D. Wright, waiting for him in the yard. In his absence, they had discovered his deceptions. Hours later, with Crouch and Wright still nearby, Stanford went into the bedroom and pulled a gun out from a bedside table, thereafter leaping into another strain of American mythos—the tortured prodigy, gone too soon. He left behind at least seven other manuscripts, completed or in process. Most enduringly, he left behind a group of friends, writers, and artists, who managed to keep his work alive, despite, and also because of, the lurid trauma of his death. One of these people was Lucinda Williams. Her song “Sweet Old World” is an elegy to Stanford.

2.

On the evening of September 20, just before the start of the second festival, a group of us gathered outside the Fenix Art Collective on Fayetteville’s downtown square. It was a rainy Friday and besides us the street was mostly dead. Hands in pockets, we introduced ourselves, telling from where we’d come and how we’d arrived. In this way, the start of the second festival was nearly identical to the first.

When the conversation turned inevitably to how we’d each come into contact with Stanford’s work, I recalled how I’d been so taken with Battlefield that I interlibrary-loaned the hard-to-come-by manuscript to the community college where I was an adjunct instructor and, in four 100-page sessions, photocopied the whole thing so that I could stay up late reading it like a gospel. Back then, I felt Stanford’s was some previously inscrutable aesthetic I’d desired but thought did not exist. I wrote to the professor who had clued me in and reported that I had found “a poetry uncle.” It would have been more honest if I had called him a “poetry blood-brother.” The unique manner in which Stanford’s poems encourage this overreaching feeling of kinship is the best way I can explain how Stanford hooks readers.

As the doors were unlocked and we entered the gallery, the difference between past and present came into focus. In contrast to my photocopying anecdote, a grad student who had flown in from a northeastern university told me of the “perfect way” he’d begun to read Frank Stanford. “It was a Friday night,” he said. “And I was drunk in Barnes & Noble.”

Of course, it is extraordinary for any book, no matter where it’s bought, to launch one into literary tourism. But mostly this comment encouraged my fear that Stanford’s magic had been somehow subdued. The ever-increasing poshness of downtown Fayetteville further encouraged this fear. For years now, Fayetteville has been awash in university money and Walmart money, and, more recently, tech-money. It consistently is ranked a top-five place to live in the U.S., and property values reflect this. I was shocked to see new, 3-bedroom townhouses, not near campus, and not walkable to downtown, listed at $348,000.

Fayetteville is no longer the quirky backwater one imagines when reading Stanford’s poems. Coming into town, I’d idled past high-end boutiques and cafes with names like French Toast Revolution—shop after shop featuring the one-of-a-kind ubiquity one expects in Hudson, New York, Charlottesville, Virginia. Particularly in their abundance, these shops are jarring in Fayetteville.

An hour earlier, while I unpacked my suitcase in the living room of the friend of a friend, he told me that the house where Stanford shot himself is an Airbnb now. I couldn’t verify this—it seems actually either not true, or no longer true—but I include it here because it might as well be true. My point is that while it might still be a stretch to say Frank Stanford has gone mainstream—and it’s maybe not a stretch when one considers Jack White’s interest in Stanford, which parallels White’s interest in bringing older musicians such as Loretta Lynn to new audiences—it’s not a stretch at all to say Fayetteville, the town that nurtured him, sure has.

Inside the Fenix Art Collective the crowd grew until, like at the first festival, there were almost 80 of us sipping craft beers against a four-dollar suggested donation. A few minutes after 7:00, festival organizer Matthew Henriksen, himself a Stanford advocate and scholar, came to the front and stood beside a scrap-metal sculpture of a deer. The deer had dollar signs etched on its flank. “Welcome,” Henriksen said, “to the second ever Frank Stanford 5K and bake sale.” The room guffawed. A series of poets read their Frank Stanford-inspired poems. We were all soggy from rain.

As the readings went on, and as I stood—a white guy amongst the overwhelmingly white crowd—my feeling that we were all clinging to something grew stronger. For a moment I imagined us as thoughtful football fans, who, having learned so much about head trauma, must now consider the immorality of our fandom, but whisper inwardly, “Don’t take this thing away from me.”

Specifically, I wondered how we’d talk about what Bill Buford called in a 2000 New Yorker article Stanford’s “frenzy of philandering.” For his story, Buford had interviewed Wright, who reported that Stanford was involved with at least six women at the time of his death. He was “handsome as the sun,” she said, and also the greatest liar she had ever known.

This was difficult to square with the present. Throughout the festival, every once in a while, a speaker would marvel at something Stanford wrote or said—for example, his quip “I don’t believe in tame poetry. Poetry busts guts,”—and wonder: “Can you imagine if this guy had Twitter?”

But, if one imagines Stanford on social media, it seems obvious that he would have been called out and exorcized from the very community gathered in celebration of him that rainy weekend. I waited for someone to mention Stanford in conjunction with #MeToo, but it never happened.

This silence I found somewhat strange, given how all the new Stanford-related publication makes clear the lasting consequences Stanford’s lies, not to mention his death, had on those around him. Ginny Crouch, in an essay that appeared originally in 1994 in The New Orleans Review—and is anthologized in Constant Stranger, a collection of writing about Stanford, published in August 2018 by Foundlings Press—discusses how she dared not return to Fayetteville for 14 years after Stanford’s suicide, particularly because some in town had wondered, “if I had nothing to hide, why I took off right after the funeral.” Her description lays bare the misogyny of a culture that would whisper accusations against a young woman to explain the actions of her cheating, by then deceased, husband. Rereading her words now should give anyone pause over the complexity of appreciating Stanford’s poems without papering over the destructiveness of his life.

Stanford’s poems themselves are also problematic. Much of this owes to their sexualized, often violent depictions of women. New readers will find Stanford ogling “booties” that “dance in leotards,” and describing women’s breasts as “rabbits waiting to be dressed.”

They will also encounter an acute homophobia made more apparent by the previously unpublished work, one of which begins, “this poem is a faggot.” As Brody Parrish Craig, a participant in a panel discussion titled, “On the Bodily in Frank Stanford’s Poetry,” put it, “Sometimes Stanford makes me want to throw the book across the floor.” Craig, who is a Stanford-admirer, a poet, and also a co-founder of InTRANSitive, a group seeking to support the trans community in Arkansas, called it disheartening to find a supposedly progressive poet writing so pejoratively. “I read stuff like this and I think, Is Frank trying to fuck with me?” Craig said.

In addition to these overt problems, there are nuanced but immature ideas about race that manifest in lines like:

oh brother I am death and you are

sleep I am

white and

you are

black brother tell me I am that which I am I am sleep and you

are death

we are

one person getting up and going outside naked as a blue jay.

Read against Stanford’s biography, these lines allude to Stanford’s suspicion that he was of mixed-race. They suggest a young person struggling with what he called “the shittiness of white people to black people” in an interview, while also working to overcome the received racism with which he grew up. But, as is also exemplified in these lines, Stanford seems frequently to want to try on blackness as a costume he might exploit creatively. His appropriation of blackness is further evidenced and complicated by the main action of Battlefield in which the narrator joins a Freedom Ride and saves the day by catching a grenade aimed at black Civil Rights protesters.

Canese Jarboe, a poet who participated on the same panel discussion as Craig, told me afterwards in an email, “It’s plain to me that Stanford set out to address important issues like racial inequality in his work, but I can admit that I am sometimes perplexed by his approach.”

Whereas the 2008 festival was conducted mostly in the library and had an energized sense of literary and even civic-engagement, the 2018 panel discussions took place in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, which, as churches tend to, imbued the goings-on with a blend of reverence, doubt, and ritual. Audience members were reminded, and forgot, and were reminded again of the relative immaturity of Stanford’s oeuvre. “Can you imagine if you were judged forever by what you wrote as an undergraduate?” one person asked. I wondered, however, if this question was the right one, given that there will never be any more of Stanford’s poems, and that, currently, we have not been spending very much time separating artists’ work from their lives.

At least one Arkansas native who I chatted with during a break felt the officially sanctioned discussions were too diplomatic. As she put it, the real question with regard to Frank Stanford has now become: “What are we gonna do with this motherfucker?”

3.

That all the new Stanford-related publication might lead paradoxically to the collective forgetting of Frank Stanford seems one possibility. What About This, the head-scratchingly noncommittal title of the collected poems, almost foreshadows this scenario. Upon finding such an ambivalent title attached to such a large volume, new readers might answer: What about it? This seems especially possible in a time of cultural molting, when many are seeking new relationships with the past, new conversations with each other, and new vocabularies for exploring these things. With regard to the complexity of Stanford, it seems plausible to throw up one’s hands in the same way the collection’s editor Michael Wiegers and Copper Canyon Press seemed to when conferring that title.

This possibility was glimpsable in the festival’s readiness to uplift other visionary outsiders—a collective what about this? The current work of Lost Roads Press, the press Stanford founded with Wright in the mid-’70s, was highlighted for its efforts to recover the poems of Besmir Brigham, another idiosyncratic Arkansas poet, who was a recluse somewhat in the vein of Emily Dickinson, and who, also somewhat like Dickinson, developed her own style of punctuation. Some festival attendees were even more restless, asking each other in the line by the coffee station, have you read Joseph Ceravolo? What about Robert Thomas? What about Daniil Kharms?

To some extent this is inevitable. Murray Shugars, an English professor at Alcorn State University who wrote his dissertation on Stanford, discussed how interest in little-known writers “creates and sustains discourse communities.” His co-panelist Amish Trivedi agreed. Part of the initial appeal of Stanford’s work Trivedi said, was “getting to talk to other cool people who had also discovered it.” All of this suggests the pull toward recovering nearly-lost artists is as much about the people doing the recovering as it is about the art itself. It also suggests the engagement Stanford’s poems encourage could be transferred elsewhere.

4.

After the festival, I asked Henriksen if there would be another gathering in 2028. “Who the heck knows,” he said. He didn’t think so. But then again, he hadn’t thought there would be a 2018 festival until he received a decade’s worth of emails from people clamoring for a sequel.

Henriksen was more optimistic about the future of reading Frank Stanford.

“It’s so much better now,” he said. “We’ve gotten more away from the bullshit. Ten years ago, so few facts about Frank were available.” Henriksen pointed to aspects of Stanford’s biography that are now more widely known: He had been diagnosed as paranoid-schizophrenic and sought treatment for alcoholism. Henriksen pointed out that Stanford’s work can now, in a more concrete way than before, be considered through the lens of mental illness.

Also, contrary to speculation that Stanford had given up poetry by the time he died, the Stanford archives, opened at Yale University in 2008, have helped researchers learn that Stanford remained involved with poetry until he died. Two of his later manuscripts, You and Crib Death, reveal him to be increasingly macabre, while also displaying his poetic growth. Henriksen quoted lines from Stanford’s 1978 poem “Terrorism,” in which he writes: “I am / Going to take it all out, in one motion, / The way you taught me to clean a fish… / And I will work that dark loose / From the backbone with my thumb.”

“Yes, they’re dark and death-obsessed. But you see the images starting to speak more,” Henriksen said. “His lines become more lucid. And then, of course, he’s gone.”

In Henriksen’s view, new information will help new readers put aside the rockstar-poet myth and embrace more authentically the complexities of Stanford’s poetry.

But this is something that has been hoped about Stanford since the time of his death. After Stanford’s suicide, the brief biography that accompanied some early printings of The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You ended with the phrase, “Finally there is the work.” In What About This, Michael Wiegers reprints this phrase in wistful font as an epigram above his editor’s note.

In my view, however, this is a wish for a distinction between person and poem that Stanford never had and that he ensures readers will never have either. His last poems depict him playing card games with death, staging shooting matches with death, and being chauffeured by death in a black Cadillac. “All I am is a song sung by the dead and I know it all of my days,” he writes in Battlefield. It’s undeniable that these images foretell a death that actually occurs. What Brody Parrish Craig termed the “violent materiality” of Stanford’s poems cannot be divorced from the violence Stanford did against his own body. The journalist Bill Donahue, in a 2015 Men’s Journal article, summed this up aptly, if blithely, calling Stanford’s suicide his “last poem, written in blood.”

So, what about this?

At the conclusion of the panel discussions, I raised my hand and asked from the audience: “What does it mean to read Frank Stanford in 2018?” I asked because I really didn’t know the answer. The panelists didn’t know either. Jarboe finally said, “I don’t know what Frank Stanford can show us about the present moment. We just have to keep grappling, I guess.”

5.

For the last few months, I’ve attempted some of this grappling. Here’s what I’ve come up with: Rather than make impossible distinctions between the person and the poems, my hope is that Frank Stanford allows readers to engage in a more nuanced conversation about toxic masculinity that gets beyond the dichotomy of either demonizing Stanford for his sins or demonizing readers who would ignore them. To this end, I keep coming back to something Stanford’s friend Bill Willett spoke about—that is, how Stanford’s mother consistently called him her “chosen child.” Apparently, Stanford long interpreted this merely as a term of endearment. “Like night and day,” Willett said of the difference in Stanford after learning the literal meaning of “chosen child.” To Willett, who is currently working on publishing a Stanford biography, this also explains partially Stanford’s lechery: “Subconsciously, he felt he’d been rejected by his birth mother, and that he’d been rejected by Dorothy when she revealed his adoption to him. Not that this makes it okay, but I think you can see, with all the sleeping around, he’s hedging his bets against getting rejected again.”

Now that I am a parent and newly 40, I am increasingly inclined to see Stanford not as a poetry uncle, but as a chosen child—one who gains in extraordinary fashion the wounding, adult knowledge that things are not what they seem. Valiantly if imperfectly, I see him questioning over and over again, his sense of self and also his whiteness. This is part of what makes the speakers of his poems so endearing as they go about exploring “the strange country of childhood / like a dragonfly on a dog-chain,” and so devastating when he writes in his poem “Lies”: “I don’t know my past / like the back of my hand / I have forgotten what flag I fly.”

In a letter included in Hidden Water that Stanford sent to the poet Alan Dugan, he discusses Francis Gildart, the protagonist of Battlefield, writing: “The character is endowed with the gift of second sight at birth. What would seem to most a blessing is, in fact, a curse. To expiate that curse, he sets out in a raft, alone and bound, and lets the river carry him where it may. He is constantly in pain.” Stanford might as well be talking about himself. The self-mythologizing intrinsic to his poetry has also become a curse. For readers, this implies that if we can’t unravel Stanford it is because no matter how much he writes, no matter how much he drinks or sleeps around, he can’t unravel himself.

Not only can’t we unravel poem from person from myth, nor should we attempt this unravelling. By the time we are drunk on Frank Stanford, we are already at the root-spring of a foundational, national dream of rurality. We are already skinny-dipping with what lives there: a purely American, violent and vulnerable, sexy and decrepit, masculine self. This is not something to ignore. Rather, it brings up questions we should try to answer. Questions such as: What if the magic of Stanford’s poems is inextricable from trauma inflicted on others? How do we handle this realization once we’ve already become a poet’s fans, and once his work has already inspired our own? Is cognitive dissonance required, or is there space for thinking about this complexity that does not encourage complicity?

In the incompleteness of Stanford’s oeuvre, there is ultimately an opportunity to consider how we construct ourselves as readers. This means we might also ask the extent to which Frank Stanford’s myth and poems, in their casting about for identity, self-knowledge, and love, implicate us? We might acknowledge that we, and many people we know, cast about similarly. In the wake of #MeToo, aren’t the lasting repercussions of this casting-about that with which we’ve been reckoning? I want to believe that facing these questions could allow readers to imagine the reconciliation and healing Stanford never got around to. We might do this imagining not only to preserve his legacy but to imagine new paths for ourselves.

This is because even if everyone stopped reading Frank Stanford, we couldn’t stop reading Frank Stanford. We’ve practically co-authored him by now. He’s like a song you swear you’ve never heard but already know how to hum. We live his dream. In this context, the most relevant question becomes: What about us?