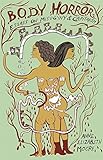

As Anne Elizabeth Moore states in her 2017 collection, Body Horror, chronic illness is more common in women than men, so it is no coincidence that these are the diseases society often ignores. This point is in direct conversation with Zoje Stage’s Baby Teeth (St. Martin’s Press, July 2018), a delicious literary thriller that debuted last month.

If you haven’t discovered Baby Teeth, the novel is told from the perspective of two third-person narrators: Suzette, a stay-at-home mother recovering from surgery for Crohn’s disease; and Hanna, her nonverbal 7-year-old. Hanna is an angel when her father, Alex, is around, but left alone, she terrorizes her mother. Seeing her mother’s illness as a sign of weakness, she looks for ways to sabotage her, to damage her. Bottom line: Hanna loves Daddy and wants Mommy out of the way. Permanently.

Despite all of this, I felt sympathy for Hanna. I could see where this little girl, though drastically misguided, was coming from, thanks in large part to Stage’s masterful use of language. I reached out to St. Martin’s Press, who graciously gave me a review copy of the novel and put me in touch with Stage for this interview.

Despite all of this, I felt sympathy for Hanna. I could see where this little girl, though drastically misguided, was coming from, thanks in large part to Stage’s masterful use of language. I reached out to St. Martin’s Press, who graciously gave me a review copy of the novel and put me in touch with Stage for this interview.

The Millions: Zoje, thank you so much for agreeing to discuss your novel with me. I hate the word “unputdownable” because it feels like overused marketing copy, but in the case of Baby Teeth, it was true. I started reading around 7 o’clock one evening and only emerged from my couch five hours later—dazed, dehydrated, finished ARC in hand.

Baby Teeth has been hyped as a new take on the “bad seed” genre, and while it excels as a summer thriller, it’s also gotten buzz from critical outlets like The New York Times Book Review. With that in mind, I want to explore your novel on the level of writing as craft.

First, I have to say, I love your novel’s gray areas. Hanna isn’t 100 percent unsympathetic, and as the reader learns, Suzette isn’t a fully blameless victim either. Do you think this effect would have been possible without the two third-person points of view? Were the earliest drafts told in this alternating perspective?

Zoje Stage: Before I started writing this novel I had to figure out how to tell it—and it was the decision to write it in dual POV that set me on my way. If I had told the story only from Suzette’s perspective, not only would Hanna have seemed less sympathetic, but I think the one-sided aspect would have derailed some of the sympathy readers have for Suzette, too. In addition, a lot of the tension in the book comes from the dual perspective of seeing how these two characters interpret the same event differently, which makes people question if one of them is more right than the other.

TM: So true. There’s something about such different takes on the same event that does it for me. Did the characters’ voices come to you fully formed or more gradually? I’m especially curious about Hanna, who, though mute, has a rich, almost-synesthetic inner life. When she tries to speak, alone in her room, the first chapter says, “bugs fell from her mouth, frighteningly alive, scampering over her skin and bedclothes.” The novel quickly cashes in on a side “benefit” of her mutism—“making Mommy crazy”—but is there a deeper reason Hanna won’t speak? In the opening chapter, Hanna opines that “Words, ever unreliable, were no one’s friend.” (This was the moment I, a commiserating writer, fell in love with your book.)

ZS: Hanna’s voice arrived fully formed, and I loved writing her chapters. Because she’s not the biggest fan of words, I tried to think from the perspective of what things looked like to her. I think Hanna has many reasons for not speaking: an initial dislike of her own voice, a frustration with not being able to say things as “richly” as the images she sees in her head, and the awareness that it gets her a certain kind of attention. That attention goes back and forth between parental concern and annoyance, but it gives Hanna her own way to feel special. Her mutism became a sort of obsession where, after doing it for so long, she truly doesn’t know how to stop.

To a certain degree, Hanna knows she’ll lose her identity if she begins speaking, and that frightens her. Who will she become? And thank you for singling out the “Words, ever unreliable, were no one’s friend” line—it’s one of my favorites in the book! It makes me laugh every time I read it, because of course I make my living with words. But Hanna experiences words as being inadequate, having found she could never articulate all of her feelings or thoughts.

TM: Let’s talk about setting for a moment. Though horrible things happen outside of the Jensen family’s home, I felt the greatest frisson of fear when Suzette was alone in the house with her daughter. This claustrophobic, oppressive feeling reminded me of the way each night in a horror film offers one more scare, one more piece of the puzzle. I was fascinated by the way the house Suzette and Alex designed together—a symbol of their love, much like their child—could grow into this warped and violent nightmare. Can you speak to any influences you had when developing this mood for your novel?

ZS: Once upon a time, the concept behind this story existed as a screenplay I’d written and hoped to direct, and mood was the single most important aspect. I was very influenced by European cinema, which often has a “cool,” detached feel, even while delving into realism. The mood in my book was inspired by elements from two particular films: Let the Right One In (a Swedish film from 2008) and Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (a 1975 Belgian film). I wanted to have this beautiful, pristine domestic environment that becomes a prison for the woman who’s there all day. And the house, in my opinion, with its sophistication and cleanliness, is very “adult,” as if neither Suzette nor Alex ever quite made room for a child.

TM: I didn’t catch that at first, but you’re absolutely right. There aren’t many (or any) Hanna-friendly spaces in the house. With that in mind, it’s interesting to consider that Suzette sees Hanna as her rival for Alex’s affection and even fears that Alex will side with their daughter over her. I read this fear as not just emotional, but also a very real fear for her financial livelihood. Because of her husband’s career as an architect, Suzette has been able to take years off of work to face motherhood and life with Crohn’s disease. Even so, Suzette frequently worries about “proving her worth,” as though she will be tossed away if she is not beautiful or useful. Does her fear of being left financially alone factor into her more irrational fear of competing with a 7-year-old for her husband’s love?

ZS: It is terribly unfortunate that Suzette feels about herself and her life that she would be nothing without Alex. And as her memories in the novel show, it doesn’t help that she didn’t experience unconditional love from her own mother. Suzette can easily envision a possibility where Alex loves Hanna unconditionally—because that’s what good parents “should” do—while his love for her comes with conditions. Her health improved during the early years of their relationship, which undoubtedly was an ego boost for him, but she fears what will happen if her health spirals out of control. There are so many ways that it could impact Alex, from injuring his selfish pride to forcing him into a caregiver role to opening his eyes to how she sees herself: disgusting, on a physical level.

And absolutely there is a financial concern. Perhaps of interest to readers is the fact that I’ve had Crohn’s disease for 35 years. I’d hoped that by publishing novels I could improve my quality of life, as I was living on a [federal] disability payment of $627/month. So I’m personally familiar with this scary scenario of trying to keep your head above water while living with a chronic illness and not being well enough to work full-time.

Suzette understands her limitations and knows that working full-time may never be in her future. Making things work with her husband is an imperative, and not just because she loves him. Since I like to pretend that my characters exist separately from me, I have to wonder if Hanna, very early in life, caught on to Suzette’s imbalanced love: that Alex was the center of her universe, not her child. Is there a possibility that what Hanna once wanted was her mother’s love?

TM: Yes! I feel this so strongly. Multiple sclerosis, which my mother has lived with for three decades now, can be exhausting for its patients and can make emotional accessibility difficult. To use a common analogy, I now understand that my mother only has so many spoons per day, and some days there aren’t spoons enough for that connection. I wish I had understood this when I was Hanna’s age.

Wow. Zoje, thanks so much for this interview. I hope that, if there isn’t a sequel, we can get a film version of Baby Teeth. To close, I have to ask: What is life like now, on the other side of your publication date? Are there any Zoje Stage projects in the works?

ZS: The question I am most frequently asked—almost daily, via social media—is if I will write a sequel. I know I disappoint readers when I say no, but I consider the story set in its trajectory. One of the things that is most interesting to me is how each reader brings their own interpretation of that trajectory, and so often what I’m really being asked is “Will you write another book with evil Hanna?” Every once in a while a reader has a different sensibility and a different understanding of Hanna—where she is a troubled girl in a deeply dysfunctional family, but is not without hope. I love that readers are projecting these characters into the future on their own, but because I fall on the minority side—of believing that there is hope for Hanna and her family—it seems unlikely that I could write the satisfying sequel that many readers want.

That said, I have a literary horror novel well in hand, with a publication date around winter 2019. And I have another book in progress, a bit more of a thriller. I’ll keep it all vague, but rest assured I am a busy, busy writer.