1.

As much as I may rack my brain, there are 15 minutes or so in the dark that I can’t account for and that I’ll never get back—15 minutes during which, I have to think, that creep’s hands were touching my body. It’s a weird thing to think about all these years later, this weird little grain of rice in my consciousness, a scratch where the record skips. The truth is I will never know what happened, exactly. None of it will ever be resolved. He didn’t rape me, at least in part because he didn’t get the chance. He probably touched me, roamed his hands all over my body, but who’s to say? Only he could. I was passed out.

It was the fall of my senior year of college. A few days before, I’d gone to happy hour with my boyfriend and he’d dumped me shortly after the pizza arrived. I was crushed and caught off guard, and my incredibly intelligent way of responding to this was to rebound, or at least try to. The weekend came. I slid my bruised ego into the World’s Tiniest Dress and went to a party at the house of a grad-student friend of mine. I didn’t usually go to strange parties because I had my boyfriend and our tight-knit group of friends, except now I didn’t have the boyfriend and I was too embarrassed to see the friends. I left my apartment with the idea I’d do something dumb—kiss someone or something. If he heard about it later, all the better. That was the point.

When the two guys started talking to me at the party, I was drunk. Even so, some lizard part of my brain knew that when they asked me to leave with them, the right answer was nope. Drunk as I was, I could feel them watching me closely, so closely that I can still see the deep muddy brown of one’s eyes, his white-blond eyelashes. They were DJs, they said, and they were going to a late-night rave. I should come, too. They could get me in. They’d give me a ride. No thanks, I said, and stumbled off to the tiny guest room my friend had promised to me. She had this old millworker’s house. The bed was narrow with some antique, almost Dickensian frame. I remember pulling the blankets over me and staring at the wall a minute, feeling disappointed and lonely and, even before anything else happened, just incredibly ashamed of myself. Then I closed my eyes.

2.

Flash forward, 14 years later. It’s the fall of 2017; I’m talking about #MeToo with a friend and we start coming up with a list of literary characters who, had they been real, might now be exposed as rapists, sexual harassers, workplace bullies, and/or terrible boyfriends. A dark joke, our list is long but hardly comprehensive: Humbert Humbert, Oblonsky, Mr. Rochester, Steven Rojack. Well. You’re kind of spoiled for choice.

One of the lesser-known names on the list was Patrick Standish, the main male character in Take a Girl Like You, Kingsley Amis’s 1960 novel. In his era, of course, Amis was a near-ubiquitous man of letters who wrote novels as well as movie and restaurant reviews, poetry and criticism. He’s not nearly as widely read now, despite the New York Review of Books recently reissuing much of his catalogue. If people know Amis’s work, they tend to know his name-making first novel, 1954’s Lucky Jim, or perhaps The Old Devils, which won the Booker Prize in 1986. It’s a shame, because Take a Girl Like You is among his best—a great work of art, deeply moral and wonderfully realized. A lost classic.

One of the lesser-known names on the list was Patrick Standish, the main male character in Take a Girl Like You, Kingsley Amis’s 1960 novel. In his era, of course, Amis was a near-ubiquitous man of letters who wrote novels as well as movie and restaurant reviews, poetry and criticism. He’s not nearly as widely read now, despite the New York Review of Books recently reissuing much of his catalogue. If people know Amis’s work, they tend to know his name-making first novel, 1954’s Lucky Jim, or perhaps The Old Devils, which won the Booker Prize in 1986. It’s a shame, because Take a Girl Like You is among his best—a great work of art, deeply moral and wonderfully realized. A lost classic.

Still, to make this argument, I’ve got to spoil it for you, and this is a novel which turns on an essential one-two punch, a lot like that Wilco song, “She’s a Jar,” that you can only hear for the first time once. It’s a funny, sometimes-rapturous love story that ends with a rape.

Jenny Bunn meets Patrick Standish. She’s a virgin and he’s a seasoned, self-aware lothario. They fall in love (“she had a sort of permanent two gin and tonics inside her” while “he had felt the wing of the angel of marriage brush his cheek, and was afraid”). But Jenny still isn’t quite ready to have sex, and Patrick spends several hundred pages trying in vain to seduce her. At last, he breaks up with her at a party, telling her, “We’re finished. Even if you walked in on me naked I wouldn’t touch you.” In despair, Jenny gets super drunk and passes out in a guestroom:

It all faded away. Time went by in the same queer speedless way as before. Then Patrick was with her. He had been there for some minutes or hours when she first realized he was, and again was in bed with her without seeming to have got there. What he did was off by himself and nothing to do with her. All the same, she wanted him to stop, but her movements were all the wrong ones for that and he was kissing her too much for her to try to tell him. She thought he would stop anyway as soon as he realized how much off on his own he was. But he did not, and did not stop, so she put her arms around him and tried to be with him, only there was no way of doing it and nothing to feel. Then there was another interval, after which he told her he loved her and would never leave her now. She said she loved him too, and asked him if it had been nice. He said it had been wonderful, and went on to talk about France.

Their host comes into the room, realizes what Patrick has done, and kicks him out of the house. So maybe it’s perverse, but I feel as though I am in a kind of catbird seat for understanding all this, though it’s true I never bobbed up to consciousness like Jenny Bunn did. In my case, I just woke up the next morning, with no interval of awareness. I helped my friend clean up, drank a cup of coffee, drove home. I didn’t know anything before four o’clock that afternoon, when she called me and told me she’d thought it over. If it had happened to her, she’d decided, she’d want to know. One of those guys got in bed with you, she told me. He’d taken off his pants but didn’t seem to have an erection. He’d only been in there a few minutes. He hadn’t had time to do anything. Anyway, she’d kicked him out of the house. I thanked her for doing that and hung up the phone. I was sitting on my bedroom floor by this point, because my legs had given out for the first time in my life.

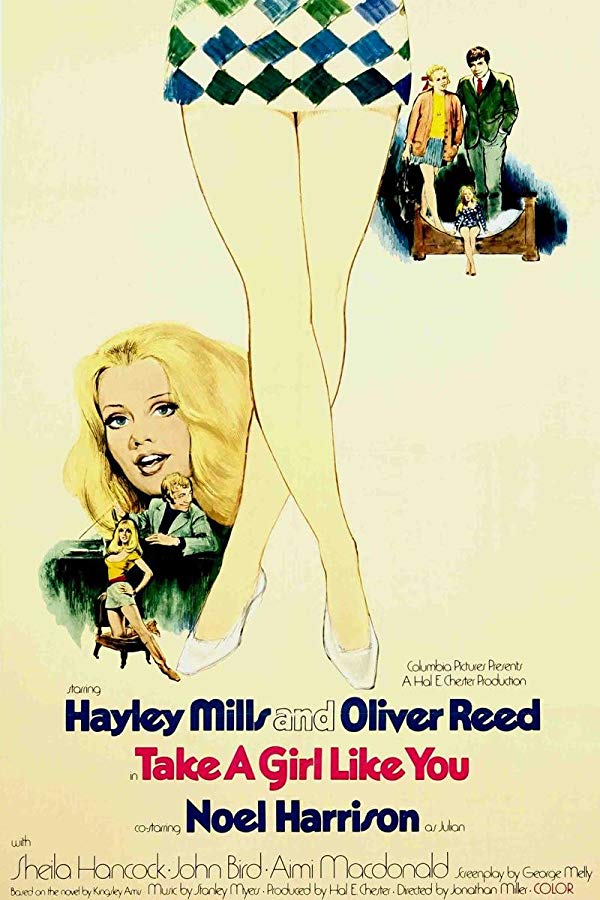

On the surface, Take a Girl Like You is a sex comedy, and tellingly, not every contemporary critic believed Jenny’s experience to be rape. In Postwar British Fiction, published in 1962, James Gindin describes the novel’s conclusion this way: “Jenny loses her virginity, but not as a result of moral or immoral suasion; Patrick tricks her into capitulation while drunk” (a view Merritt Moseley would decry in 1993). The 1970 movie adaptation, starring Hayley Mills as Jenny Bunn, portrayed the story as a kind of sexual slapstick, changing the ending so that Jenny chooses to sleep with another character. Then Patrick chases Jenny down a road in what’s meant to be a madcap scene. Cue a breezy theme song by The Foundations, roll credits.

But Kingsley Amis knew that what happens to Jenny is terribly wrong, though the word “rape” is not used, even by Jenny herself. The next morning, she wakes up puking, hungover:

Jenny decided reading would be too much for her. She smoked a cigarette until her insides felt as if they were getting as far away from the middle of her as they could. Then she put it out. But even with that big hollow in her interior she was recovering enough to start getting the first edge of thought. For it to have gone like that, almost without her noticing. At that she rebuked herself, sitting up straight in her chair. What was so special about her that it should have happened the way she imagined it, alone with a man in a country cottage surrounded by beautiful scenery, with the owls suddenly waking her up in the early hours and him putting his arms around her and soothing her, and then in the morning the birds singing and the horses neighing, and her frying eggs and bacon and spreading a wholemeal loaf with thick farm butter? A lot of sentimental rubbish, that was—she would be asking for roses and violins next. Much better be sensible, think herself lucky it had not gone for her as it did for some, sordid and frightening and painful and with someone you hated or hardly knew. That was happening every day.

That’s the crux of the novel, its turning from comic to tragic. Jenny deserves better and she doesn’t get it. In fact she is almost pathetically grateful that she has had it no worse. As light as Amis’s touch is here—Take a Girl Like You is not political, not a polemic—you can’t mistake his grief and revulsion. Amis would later describe Patrick Standish as the worst person he’d ever written about, and this when he made a career of writing about unpleasant people, including Roger Micheldene, the hideous antihero of 1963’s One Fat Englishman. Amis knew he wasn’t writing about any straightforward “capitulation.”

That’s the crux of the novel, its turning from comic to tragic. Jenny deserves better and she doesn’t get it. In fact she is almost pathetically grateful that she has had it no worse. As light as Amis’s touch is here—Take a Girl Like You is not political, not a polemic—you can’t mistake his grief and revulsion. Amis would later describe Patrick Standish as the worst person he’d ever written about, and this when he made a career of writing about unpleasant people, including Roger Micheldene, the hideous antihero of 1963’s One Fat Englishman. Amis knew he wasn’t writing about any straightforward “capitulation.”

Take a Girl Like You is often compared with Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa, but I say the better foil is Nabokov’s Lolita, in which the subtle, below-surface moral weight of the novel is with the victim—all of it springing from her loss and victimization. The Lolita comparison is, yes, a little ironic because Amis hated Lolita and hated Nabokov. Still, there’s a central likeness. Nabokov did not intend that we should fall for Humbert Humbert’s artsy, tortured rationalization of rape; Amis didn’t intend that Patrick Standish be taken for a sympathetic hero, either. Patrick is charming and funny and fun, even erudite, and he’s also a complete asshole. (As well as raping Jenny, Patrick sleeps with his boss’s 17-year-old daughter.)

Take a Girl Like You is often compared with Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa, but I say the better foil is Nabokov’s Lolita, in which the subtle, below-surface moral weight of the novel is with the victim—all of it springing from her loss and victimization. The Lolita comparison is, yes, a little ironic because Amis hated Lolita and hated Nabokov. Still, there’s a central likeness. Nabokov did not intend that we should fall for Humbert Humbert’s artsy, tortured rationalization of rape; Amis didn’t intend that Patrick Standish be taken for a sympathetic hero, either. Patrick is charming and funny and fun, even erudite, and he’s also a complete asshole. (As well as raping Jenny, Patrick sleeps with his boss’s 17-year-old daughter.)

You could even argue that Take a Girl Like You is in some senses a subtler and certainly a more realistic portrayal of rape because Jenny is not eye-poppingly young, and there’s no continuous, hysterical fireworks of justification. Amis gives both Jenny’s and Patrick’s perspectives in alternating sections, and Jenny’s experience is as deftly handled as it is, in part, familiar. I read the novel swearing under my breath. Kingsley Amis nailed it.

You could even argue that Take a Girl Like You is in some senses a subtler and certainly a more realistic portrayal of rape because Jenny is not eye-poppingly young, and there’s no continuous, hysterical fireworks of justification. Amis gives both Jenny’s and Patrick’s perspectives in alternating sections, and Jenny’s experience is as deftly handled as it is, in part, familiar. I read the novel swearing under my breath. Kingsley Amis nailed it.

The natural next question is, how’d he do that? In his lifetime, most especially in his later career, Amis was notorious for his misogyny. As the biographies reveal, he was himself a prolific womanizer who sometimes felt guilty about it and often wrote about that guilt, not least of all in Take a Girl Like You. That’s not necessarily the same thing as being a sexist, repentant or otherwise. The evidence is mixed; you can neither dismiss him as a misogynist nor declare his misogyny merely supposed and perceived, as Paul Fussell did in his 1994 book on Amis, The Anti-Egotist. To hear Fussell tell it, Amis is merely “tired of the automatic imputation of virtue and sensitivity to the female character … Women, Amis knows, can be fully wicked as men. They can lie and cheat and destroy with the best of them.” That’s true and yet not the whole picture. In some of the novels, the women do nothing but lie, cheat and destroy while the men struggle vainly to run the world in spite of this ongoing assault. Is that still satire?

The natural next question is, how’d he do that? In his lifetime, most especially in his later career, Amis was notorious for his misogyny. As the biographies reveal, he was himself a prolific womanizer who sometimes felt guilty about it and often wrote about that guilt, not least of all in Take a Girl Like You. That’s not necessarily the same thing as being a sexist, repentant or otherwise. The evidence is mixed; you can neither dismiss him as a misogynist nor declare his misogyny merely supposed and perceived, as Paul Fussell did in his 1994 book on Amis, The Anti-Egotist. To hear Fussell tell it, Amis is merely “tired of the automatic imputation of virtue and sensitivity to the female character … Women, Amis knows, can be fully wicked as men. They can lie and cheat and destroy with the best of them.” That’s true and yet not the whole picture. In some of the novels, the women do nothing but lie, cheat and destroy while the men struggle vainly to run the world in spite of this ongoing assault. Is that still satire?

It is, in the case of 1978’s Jake’s Thing, where the crazy women are leavened out with pathetic women and no character, the men included, is in any sense to be admired. You can’t miss the comic brio of its penultimate paragraph:

It is, in the case of 1978’s Jake’s Thing, where the crazy women are leavened out with pathetic women and no character, the men included, is in any sense to be admired. You can’t miss the comic brio of its penultimate paragraph:

Jake did a quick run-through of women in his mind, not of the ones he had known or dealt with in the past few months or years so much as all of them: their concern with the surface of things, with objects and appearances, with their surroundings and how they looked and sounded in them, with seeming to be better and to be right while getting everything wrong, their automatic assumption of the role of injured party in any clash of wills, their certainty that a view is the more credible and useful for the fact that they hold it, their use of misunderstanding and misrepresentation as weapons of debate, their selective sensitivity to tones of voice, their unawareness of the difference in themselves between sincerity and insincerity, their interest in importance (together with noticeable inability to discriminate in that sphere), their fondness for general conversation and directionless discussion, their pre-emption of the major share of feeling, their exaggerated estimate of their own plausibility, their never listening and lots of other things like that, all according to him.

But 1984’s Stanley and the Women is a bridge too far. There’s just one minor female character who isn’t a complete emotional monster, while every male character is sympathetic. Here the satire, if it still is satire, is as sour, unrelieved, and unrelenting as anything Amis ever wrote. In the U.S., several publishers turned down the book because the women on their boards objected. There’s a nadir in the poetry, too, though the 1987 poem that begins “Women and queers and children / cry when things go wrong” went unpublished and unfinished. In his excellent The Life of Kingsley Amis, Zachary Leader described the poem as “calculated to cause the maximum possible offense.” (I’d add, without glee, that it’s also a bit rich coming from Amis, who had a paralyzing fear of the dark and couldn’t be left alone.)

But 1984’s Stanley and the Women is a bridge too far. There’s just one minor female character who isn’t a complete emotional monster, while every male character is sympathetic. Here the satire, if it still is satire, is as sour, unrelieved, and unrelenting as anything Amis ever wrote. In the U.S., several publishers turned down the book because the women on their boards objected. There’s a nadir in the poetry, too, though the 1987 poem that begins “Women and queers and children / cry when things go wrong” went unpublished and unfinished. In his excellent The Life of Kingsley Amis, Zachary Leader described the poem as “calculated to cause the maximum possible offense.” (I’d add, without glee, that it’s also a bit rich coming from Amis, who had a paralyzing fear of the dark and couldn’t be left alone.)

Even if you wanted to, you couldn’t separate art from artist here because the offense is the whole point. Still, that convention—holding out the work from the person who made it—is flimsy to begin with. It presents a false choice. In the end, we don’t really get to choose between great works and flawed people. We get both. As Christopher Hitchens wrote of H.L. Mencken: “He had very grievous moral and intellectual shortcomings and even deformities … But any reductionist analysis of Mencken runs the risk of ignoring a fine mind that engaged itself in some high duties.”

It’s an uneasy position for this Amis fan. But what’s the alternative, not reading him at all? I love his work. Even in the minor novels, the ones that don’t quite come off, there’s always, always the intelligence, the bite in the closely observed details and those trademark Amis sentences that are wonderfully precise and yet never pretentious, never overwrought. My copies of his books are dog-eared and misshapen from repeated drops in the bath. I’m always in some stage of rereading The Old Devils, and I keep multiple copies of 1990’s The Folks That Live on the Hill because I’m always pushing it on friends. About the time I was at risk of rape at that party in 2003, I was working my way through everything Amis ever wrote, because my college library had every title. I have never encountered that happy condition since, and it almost makes me wish I’d never left school. Maybe you’re not supposed to have a favorite writer—maybe he shouldn’t be my favorite writer—but Kingsley Amis is my favorite writer.

It’s an uneasy position for this Amis fan. But what’s the alternative, not reading him at all? I love his work. Even in the minor novels, the ones that don’t quite come off, there’s always, always the intelligence, the bite in the closely observed details and those trademark Amis sentences that are wonderfully precise and yet never pretentious, never overwrought. My copies of his books are dog-eared and misshapen from repeated drops in the bath. I’m always in some stage of rereading The Old Devils, and I keep multiple copies of 1990’s The Folks That Live on the Hill because I’m always pushing it on friends. About the time I was at risk of rape at that party in 2003, I was working my way through everything Amis ever wrote, because my college library had every title. I have never encountered that happy condition since, and it almost makes me wish I’d never left school. Maybe you’re not supposed to have a favorite writer—maybe he shouldn’t be my favorite writer—but Kingsley Amis is my favorite writer.

That Amis remains a complex figure is fitting, full stop. There remains something akin to the “problem from hell” that Martin Amis identifies in Nabokov’s work. In the case of Amis senior, it is not a recurring preoccupation with the “despoiliation of very young girls”; it’s a recurring, vigorous anti-woman streak that does not at all preclude him from seeing what women sometimes suffer at the hands of men. In 1969’s The Green Man, for instance, the narrator labors to banish the ghost of a long-ago rapist. And Amis’s 1976 alternate-world novel The Alteration, as William Gibson has written, “depicts the oppression of patriarchy, given full reign by theocracy, as thoroughly as any novel prior to, say, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.”

That Amis remains a complex figure is fitting, full stop. There remains something akin to the “problem from hell” that Martin Amis identifies in Nabokov’s work. In the case of Amis senior, it is not a recurring preoccupation with the “despoiliation of very young girls”; it’s a recurring, vigorous anti-woman streak that does not at all preclude him from seeing what women sometimes suffer at the hands of men. In 1969’s The Green Man, for instance, the narrator labors to banish the ghost of a long-ago rapist. And Amis’s 1976 alternate-world novel The Alteration, as William Gibson has written, “depicts the oppression of patriarchy, given full reign by theocracy, as thoroughly as any novel prior to, say, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.”

To dismiss Amis as a misogynist would be an attempt to resolve the sort of frustrated justice he himself depicted over and over again. Great works, flawed people. The facts do not really compute.

3.

I never saw that guy, the one who got in bed with me, ever again. I got up off the floor and moved on with my life because it did not occur to me that there was a choice. I did not consider calling the police, not for a second. I was too embarrassed as it was, and in my gut I know that if I had been raped that night, I wouldn’t have reported it. Imagine saying to the police: I’d just been dumped. I was very drunk. I was wearing this napkin of a dress. I don’t remember it. Dear God. Even now. I didn’t even say #MeToo last fall when the hashtag was trending because I didn’t want to have to explain anything to anyone. Also because I didn’t think of it as anything special. Also because it wasn’t the worst thing that ever happened to me. The breakup hurt me much worse, and for longer. For me, “trauma” doesn’t seem like the right word; whatever happened to me that night I just took as part of the fabric of experience. Why make a fuss, and open myself to judgement and blame? Wouldn’t I have to be a purer victim for it be really wrong in the eyes of our culture?

This points to the ultimate triumph of Amis’s Jenny—his sense of the full scope of her predicament. Jenny not only moves on with her life; she makes up with Patrick. In the last lines of the novel, Patrick says, “It was inevitable,” and Jenny responds, “Oh yes, I expect it was. But I can’t help feeling it’s rather a pity.” In the sequel, 1988’s Difficulties with Girls, Jenny and Patrick are married, have been married eight years as the novel begins. The rape has receded from view, becoming just another part of the knit of Jenny’s experience, and in this way, I’m convinced, Amis brings our dilemma into focus as few other novelists ever have.

This points to the ultimate triumph of Amis’s Jenny—his sense of the full scope of her predicament. Jenny not only moves on with her life; she makes up with Patrick. In the last lines of the novel, Patrick says, “It was inevitable,” and Jenny responds, “Oh yes, I expect it was. But I can’t help feeling it’s rather a pity.” In the sequel, 1988’s Difficulties with Girls, Jenny and Patrick are married, have been married eight years as the novel begins. The rape has receded from view, becoming just another part of the knit of Jenny’s experience, and in this way, I’m convinced, Amis brings our dilemma into focus as few other novelists ever have.

The question that #MeToo is answering is, in part: What do we do with these experiences? How do we describe them and how do we integrate them into our lives, and why have we tried to integrate them? How have we been encouraged to erase them? Shouldn’t we hold them apart? What exact behavior becomes legible here, and who benefits when we keep our mouths shut? Almost 70 years after Take a Girl Like You, we’re having that public conversation. Amis was there in 1960. Rereading it and the rest of his catalogue over the last couple of months, I’ve come to see again the particular wingspan of his accomplishments as a writer. The range of the novels, the humor and precision in the poems. All that lively, fun, cutting intellectual energy put to such wonderful use—most of the time. If we’re left with irreducible ambiguities (and indefensible shit like “women and queers and children”), well, at least we get the art, too.

As Amis knew, misogyny and rape don’t take place at some great remove from art and life. They’re part of an ambient hum that drifts in and out of our consciousness, moving from background to foreground and back again. Then as now, that’s the awful problem.