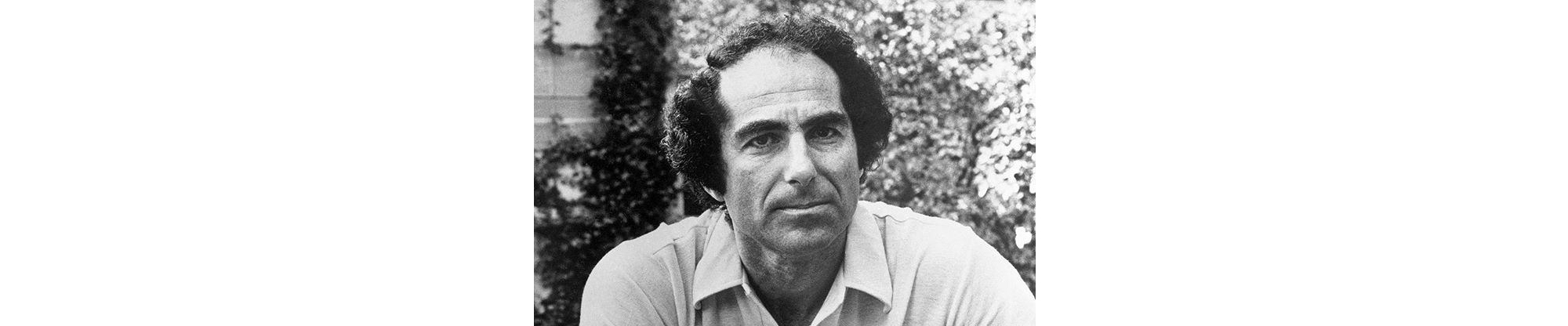

Al Alvarez, Joyce Carol Oates, John Cheever, and others remember Philip Roth, the creator of iconic characters Portnoy and Nathan Zuckerman.

1. Intense

1. Intense

[University of Chicago English professor Joan Bennett] invited us to tea to meet one of her students; it was Philip Roth and the stories he was working on in Joan’s class became Goodbye, Columbus. He was very intense and had pronounced views on the department; his wife seemed rather silent. (Chicago, mid-1950s)

—From First Generation: An Autobiography, by Ernest Sirluck (University of Toronto Press, 1996)

2. Prince to My Pauper

2. Prince to My Pauper

On the first day of a course on Henry James [at the University of Chicago] in the fall of 1957, I found myself sitting next to…a dark debonair fellow in a jacket and tie who…looked like he had strayed into class from the business school…Phil Roth. With the antenna of New York/New Jersey Jews, we quickly tuned into each other. …

Phil wore GI khaki gloves inside his leather ones, but otherwise dressed like the junior faculty member that he also was, having been given a job in the College that the rest of us Ph.D. students would have killed for. …

Around the second week of class, one of the students was going on about the religious allegory that underlay Daisy Miller. [Professor Napier] Wilt asked me what I thought of this interpretation. I said that it was idiotic to read James as though he were Hawthorne. Then Phil jumped in and proceeded to show how eschewing the concrete for the symbolic “turned the story inside out,” that Daisy had to be established as an American girl of a certain class and disposition before she became of any interest as a sacrificial figure. Like two players early in the season who find they can work together, Phil and I passed the ball back and forth, running up the score of good sense. …

The one time he came to our flat, he sat there like a social worker on the edge of a couch over which I had nailed an old shag rug to cover the holes. Though we both came from the same hard-pressed Jewish middle class, his clothes, his place in the College, and the money he made from writing cast us in adult prince and pauper roles. …

During our humor binges, Phil would suddenly slip the moorings of his gifts of precise mimicry, timing, suspense, and imagery and get carried away—or better, swept away—into a wild dark sea of vulgarity and obscenity, as far out and obsessed as Lenny Bruce himself.

—From First Loves: A Memoir, by Ted Solotaroff (Seven Stories Press, 2003)

3. Meticulous Invigilator

3. Meticulous Invigilator

When Philip Roth was living in London, I went to the little apartment where he worked to collect him for lunch. While he was putting on his coat, I glanced at a page of manuscript lying beside his typewriter. Philip has one of the strongest voices of any novelist alive, effortless and apparently unhesitating, yet the page was black with tiny corrections.

“Who’s going to notice the difference?” I asked.

“You are,” he answered. “I am.”

Meticulousness is just one of the obsessions Philip and I share. When we first met 40 years ago [circa 1960] we were both angry young men with bad marriages, troublesome parents and a yearning for shiksas and literature. We had both been good students, full of high seriousness, and even now when we talk about books it’s usually about the masterworks we were taught to admire back in the fifties when we were at college—Kafka, [Nikolai] Gogol, [Henry] James. Since then I have written three novels, yet whenever I am with Philip I realize I lack the novelist’s temperament. A real novelist is an invigilator, constantly on the watch, listening, making mental notes, using whatever happens to happen and weaving it into stories. Maybe that was what James meant by “loose and baggy monsters”: the novel can accommodate everything.

—From Where Did It All Go Right? A Memoir, by Al Alvarez (Morrow/HarperCollins, 1999)

4. Boys’ Talk

4. Boys’ Talk

I have a drink, go to meet Philip Roth at the station with the two dogs on leads. He is unmistakable, and I give him an Army whoop from the top of the stairs. Young, supple, gifted, intelligent, he has the young man’s air of regarding most things as if they generated an intolerable heat. I don’t mean fastidiousness, but he holds his head back from his plate of roast beef as if it were a conflagration. He is divorced from a girl I thought delectable. “She won’t even give me back my ice skates.” The conversation hews to a sexual line—cock and balls, [Jean] Genet, [John] Rechy—but he speaks, I think, with grace, subtlety, wit. (Ossining, N.Y., 1963)

—From The Journals of John Cheever, by John Cheever (Knopf, 1990)

5. Vigilant Spectator and Critic

5. Vigilant Spectator and Critic

July 28, 1965 [Yaddo writers retreat, Saratoga Springs, N.Y.]. In the evening, to see the William Wyler film The Collector. Afterwards the Yaddo boys [and two girls] sat around in the Colonial and dissected the film, Roth as usual giving the lead…Roth is a sharp, logical analyst of character and motivation in whatever he sees and reads.  I remember that in discussing Herzog he spotted all sorts of illogicalities; when he discussed The Collector, he took it apart, spotting every possible implausibility and moral confusion. He is always outside, vigilantly himself as the spectator and critic and judge. Everything is consciously sized up all day long. This extraordinary conscious intactness!

I remember that in discussing Herzog he spotted all sorts of illogicalities; when he discussed The Collector, he took it apart, spotting every possible implausibility and moral confusion. He is always outside, vigilantly himself as the spectator and critic and judge. Everything is consciously sized up all day long. This extraordinary conscious intactness!

—From Alfred Kazin’s Journals, selected and edited by Richard M. Cook (Yale University Press, 2011)

6. Tall and Handsome

We had first met in East Hampton, Long Island, in 1966. Rod [Steiger] and I had taken a house for the summer months, and we had a good time there…bicycle-riding, swimming, performing a host of healthy summer activities. Neighbors invited us over for a drink; one of their houseguests was Philip. Already a highly acclaimed young writer—the author of Goodbye, Columbus, a fine volume of short stories—I recognized his tense, intellectually alert face immediately from photographs. Tanned, tall, and lean, he was unusually handsome; he also seemed to be well aware of his startling effect on women. I was immediately attracted to him, and he would tell me years later that he also had felt the same toward me…

We had first met in East Hampton, Long Island, in 1966. Rod [Steiger] and I had taken a house for the summer months, and we had a good time there…bicycle-riding, swimming, performing a host of healthy summer activities. Neighbors invited us over for a drink; one of their houseguests was Philip. Already a highly acclaimed young writer—the author of Goodbye, Columbus, a fine volume of short stories—I recognized his tense, intellectually alert face immediately from photographs. Tanned, tall, and lean, he was unusually handsome; he also seemed to be well aware of his startling effect on women. I was immediately attracted to him, and he would tell me years later that he also had felt the same toward me…

—From Leaving a Doll’s House, by Claire Bloom (Little, Brown, 1996)

7. Casual

7. Casual

I was talking to Philip Roth for the [Toronto Telegram]. He spoke in the tapered tone of a man who wanted to convey a casual intelligence and amiability, a man deft with an idea. Slender, a little balding, wearing a pullover V-neck sweater and a shirt open at the neck, he paced back and forth on the burgundy plank floors in his flat, and then sat at his writing desk—heavy oak, somewhat awkward to sit at—a gray metal elbow lamp clamped to the desk top, jutting into the air, it angled back over his typewriter. (New York, late 1960s)

—From Barrelhouse Kings: A Memoir, by Barry Callaghan (McArthur & Company, 1998)

8. Swarthy Glory

As JH [companion James Holmes] and I were finishing our chowder at The Tavern, toying with the notion of leaving next day, stopping our ears against an aggressive accordion and trying to compare notes on our mutual loathing of the local Catholic dishwater-blond fauna, and exclaiming, My God, there’s not one Jew in this town, much less anyone we’d ever want to know! Who should enter in all his swarthy glory but Philip Roth, and Barbara. So they sat and chatted a while, cheered us up some (we’d seen no humans hitherto), and we made a date for Wednesday, but didn’t keep it because we fled instead. (Siasconset, Mass., 1972)

As JH [companion James Holmes] and I were finishing our chowder at The Tavern, toying with the notion of leaving next day, stopping our ears against an aggressive accordion and trying to compare notes on our mutual loathing of the local Catholic dishwater-blond fauna, and exclaiming, My God, there’s not one Jew in this town, much less anyone we’d ever want to know! Who should enter in all his swarthy glory but Philip Roth, and Barbara. So they sat and chatted a while, cheered us up some (we’d seen no humans hitherto), and we made a date for Wednesday, but didn’t keep it because we fled instead. (Siasconset, Mass., 1972)

—From The Later Diaries: 1961-1972, by Ned Rorem (North Point Press, 1983)

9. Completely Likeable Person

9. Completely Likeable Person

May 15, 1974…Met Philip Roth. We went to his apartment, then out to lunch. Attractive, funny, warm, gracious: a completely likeable person. We talked about books, movies, other writers, New York City, Philip’s fame (and its amusing consequences), his experiences in Czechoslovakia meeting with writers. Ray [Smith, husband] and I liked him very much. His apartment on 81st St. is large and attractive, near the Met. Art gallery. He has another house (and another life, one gathers) in Connecticut. My Life as a Man irresistibly engaging. But one wonders at Philip’s pretense that it isn’t autobiographical.

—From The Journals of Joyce Carol Oates 1973-1982, by Joyce Carol Oates (HarperCollins, 2007)

10. Handshakes Received and Avoided

Philip Roth came with Claire Bloom to [film and stage producer] Patrick Garland’s wedding to [actress] Alexandra Bastedo in the Chichester Cathedral and to the reception afterwards in Bishop Kemp’s quarters in the cathedral grounds. Edward Kemp, the youngest teenage son of the bishop approached him. “Mr. Roth,” he asked, “may I shake you by the hand?” After his wish had been granted and he slipped away (to become in time an excellent writer/director), Philip Roth whispered, “Women at literary luncheons across America have run a mile rather than shake the hand of the man who wrote Portnoy’s Complaint. (West Sussex, England, mid-1970s)

Philip Roth came with Claire Bloom to [film and stage producer] Patrick Garland’s wedding to [actress] Alexandra Bastedo in the Chichester Cathedral and to the reception afterwards in Bishop Kemp’s quarters in the cathedral grounds. Edward Kemp, the youngest teenage son of the bishop approached him. “Mr. Roth,” he asked, “may I shake you by the hand?” After his wish had been granted and he slipped away (to become in time an excellent writer/director), Philip Roth whispered, “Women at literary luncheons across America have run a mile rather than shake the hand of the man who wrote Portnoy’s Complaint. (West Sussex, England, mid-1970s)

—From Ned Sherrin: The Autobiography, by Ned Sherrin (Little Brown, 2005)

11. Inward-Looking Self-Explorer

A feeling of authentic French provençal with faded ochre walls and pine tables where you can sit as long as you like…Thompsons, as this modest establishment on the corner of Portobello Mews and next to a new dry-cleaner’s, soon becomes known. …

Today Philip Roth is sitting at the back of Thompsons in the gloom. Like an ant-eater’s, his long snout and bright eyes are trained downwards, on the food he consumes. A book is held up close to his face; Roth most definitely does not wish to be disturbed. I’ve heard this most inward-looking and remarkable of self-explorers has a room where he writes in Stanley Gardens, up the hill. I know, despite the fact of his apparent great distance from the talk or excitements around him, that every word one says goes into the long, this head, shaped like a quill with its tufty feathers of black hair, and lies waiting to be inscribed in stone. …

Today Philip Roth is sitting at the back of Thompsons in the gloom. Like an ant-eater’s, his long snout and bright eyes are trained downwards, on the food he consumes. A book is held up close to his face; Roth most definitely does not wish to be disturbed. I’ve heard this most inward-looking and remarkable of self-explorers has a room where he writes in Stanley Gardens, up the hill. I know, despite the fact of his apparent great distance from the talk or excitements around him, that every word one says goes into the long, this head, shaped like a quill with its tufty feathers of black hair, and lies waiting to be inscribed in stone. …

The other day, Roth went so far as to invite me to join him in the dark recesses of the restaurant. We talked of nothing much, except Roth’s first wife and the novel, My Life as a Man, that he’d written about her violent and untimely death. My sympathy was brushed aside; Roth declared himself unperturbed by the outcome of his spouse’s tragic accident…

After lunch, Roth suggests I “see” his Stanley Gardens workplace. I go up the hill with him, and then up three floors to the minute flat where he sits over his desk, deep in Nathan Zuckerman, his alter ego. There is hardly any space, between desk, armchair and wall, to stand in; but somehow Roth his fitted a rubber mat, green with a swirly pattern, in this tight space, and I find myself—there is nowhere else to go—standing on it. “For my exercises,” Roth says. A silence falls, and I leave, suddenly aware I don’t want to be here at all. Whatever the “exercises” are, I definitely do not want to be a part of them. (London, 1976)

—From Burnt Diaries, by Emma Tennant (Canongate Books, 1999)

12. Monk’s Cell With a Great View

Roth’s face is lined now, his mouth has tightened and his springy hair has turned grey, but he still looks like an athlete—tall, lean, with broad shoulders and a small head. Until recently, when surgery on his back and arthritis in the shoulder laid him low, he worked out and swam regularly, though always, it seemed, for a purpose—not for the animal pleasure of physical exercise, but to stay fit for the long hours he puts in at his writing. He works standing up, paces around while he’s thinking and has said he walks half a mile for every page he writes. Even now, when his joints are beginning to creak and fail, energy still comes off him like a heat haze, but it all driven by the intellect. It comes out as argument, mimicry, wild comic riffs on whatever happens to turn up in the conversation. His concentration is fierce, and the sharp black eyes under their thick brows miss nothing. The pleasure of his company is immense, but you need to be at your best not to disappoint him. …

The New York studio…where me met to talk…is on the 12th floor, a single large room with a kitchen area, a little bathroom and a glass wall looking south across Manhattan’s gothic landscape to the Empire State Building, with a wisp of cloud around its top.

The lectern at which Roth works is at right angles to the view, presumably to avoid distraction…There is a bed with a neat white counterpane against the wall, an easy chair in the center of the room, with a graceful standing lamp beside it, all of it leather and steel and glass, discreetly modern. It is a place strictly for work, spare and chaste, a monk’s cell with a great view. (2004)

—From “The Long Road Home,” by Al Alvarez, The Guardian (Sept. 23, 2004)

13. Missed Opportunity

I went to hear Hermione Lee, an Oxford University English professor, speak at Columbia University this evening about her just published biography [of Edith Wharton]…

I arrived early at Low Library and took a seat in the third row of the nearly empty rotunda. Soon afterwards, a professorial man in a tweedy brown jacket sat down in the seat right next to me, which struck me as odd, considering that he might have been expected to leave an empty seat between us in such uncrowded circumstances.

I arrived early at Low Library and took a seat in the third row of the nearly empty rotunda. Soon afterwards, a professorial man in a tweedy brown jacket sat down in the seat right next to me, which struck me as odd, considering that he might have been expected to leave an empty seat between us in such uncrowded circumstances.

I glanced at him, thought he looked vaguely familiar, couldn’t place him, and went back to working on some writing. (I now blush to think he might have been looking at the page.) Fifteen minutes later, along came my husband, who sat down in the seat on my left. The “professor” soon moved one seat over, laying his coat across the seat between us.

When Hermione Lee took her seat onstage, I noticed her nod in greeting to the man on my right. Then, the person who introduced her mentioned that she had once written an essay on Philip Roth.

And then, of course, I knew.

I cast a sidelong glance at “the professor,” and realized the person I had studiously ignored while I continued my own scribbling was arguably our country’s most famous living literary novelist…

I had just missed the opportunity to have a 15-minute tête-à-tête with the perpetrator of Portnoy. After the Wharton talk concluded, I lamely inquired if he was Philip Roth and told him it was nice to see him. He returned the pleasantry and was off to commune with the academic types up front. (New York City, 2007)

—From “Philip Roth: Another Missed Opportunity,” by Lee Rosenbaum, Arts Journal’s CultureGrrl blog (April 12, 2007)

Image credit: Flickr/hye tyde

https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/P/B004J4WLU0.01.MZZZZZZZ.jpg