Sometimes writing fiction feels to me like that oft-used image of a godlike creator: the man pulling the strings of the marionette, orchestrating each fine movement from above the stage. One string might be character, another plot, a third setting, a fourth conflict, then dialogue, figurative language, pacing, point of view, tone, and so on in innumerable quantities. When I position myself at the center of this image—as the Writer—fiction seems like a failed proposition. Invariably, things go wrong: the strings get tangled, the synchronization is off, I lose track of what the left foot or right hand is doing, and the whole show falters. The work is revealed as amateurish and I must step down like Oz from behind the curtain to face my shame.

As a teacher, I see my students grappling with this difficulty on a daily basis. Their small successes (“Great dialogue!”) are overshadowed by all the parts that aren’t yet working. And there are so many parts, so many ways to not be working.

This is what got me started thinking about simplifying an approach to craft, or rather, trying to understand what craft elements encompass which other ones as a way to focus on manipulating the fewest elements of a story to receive the largest payoff. My answer came from another, highly-complicated field: Physics, specifically, Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity.

In layman’s terms, the Theory of Relativity proposes that the measurable properties of time and space aren’t actually as fixed as we perceive them to be. They’re subjective. In our real universe, time and space flex, expanding or contracting relative to moving objects. I began to see parallels between the time and space of the physical universe and the time and space of the fictional one. What if time and space were the only two properties the writer sought to control? Would the universe of craft choices become less overwhelming in their entirety?

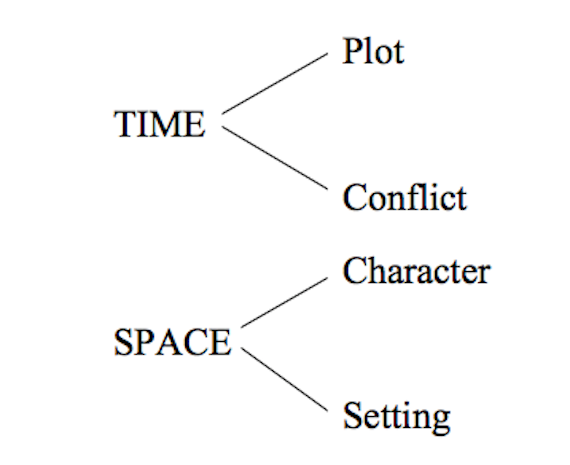

Don’t worry, there’s no math involved in any of this, but there is a diagram. A rudimentary version might look like this,

with other craft elements, such as pacing, dialogue, point of view, and so on following naturally from there.

Of what use is this to the writer? For one, it puts craft choices into perspective. The writer’s aim must be to address these two questions principally: (1) How will time be managed? and (2) What is the space of the narrative?

The first question is addressed by the work of narrative theorist Gérard Genette, whose book Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, proposes three principal ways in which writers can and do manipulate time: order, duration, and frequency.

The first question is addressed by the work of narrative theorist Gérard Genette, whose book Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, proposes three principal ways in which writers can and do manipulate time: order, duration, and frequency.

In the first, “order,” the writer may choose to present events out of chronology; associated terms include flashback and flash forward. At the macro-level, stories that do this wonderfully include Dan Chaon’s “Falling Backwards,” which is narrated, as the title suggests, in reverse order, or Brian Evenson’s “Younger,” a story about two adult sisters attempting to reconcile very different versions of a childhood memory. At the micro-level, nearly every short story is an exercise in anachronisms, borne of the nature of English’s grammatical structures and the writer’s urge to withhold.

The second, “duration,” refers to the ways in which a writer might speed up or slow down the effect of the narration, typically through the number of words she chooses to deploy for a particular moment; 10 years might last a sentence, while a minute may consume three pages. In writer’s circles, we call this pacing, and we harp frequently on the rule to show not tell, although all the best writers are masterful tellers, skilled in the art of contracting narrative time in order to squeeze the marrow from it.

Few writers are as deft at this as Lydia Davis. In her story “How Difficult,” she moves from compressed time into present time midway through the final sentence, neatly cramming years of grievances into a single phone call.

For years my mother said I was selfish, careless, irresponsible, etc. She was often annoyed. If I argued, she held her hands over her ears, she did what she could to change me, but for years I did not change, or if I changed I could not be sure I had, because a moment never came when my mother said, ‘You are no longer selfish, careless, irresponsible, etc.’ Now I’m the one who says to myself, ‘Why can’t you think of others first, why don’t you pay attention to what you’re doing, why don’t you remember what has to be done?’ I am annoyed. I sympathize with my mother. How difficult I am! But I can’t say this to her, because at the same time that I want to say it, I am also here on the phone coming between us, listening and prepared to defend myself.

We are caught, almost by surprise, by the narrator’s dilemma—her ownership and disavowal of her own pettiness, the depth of her grief over neither being able to accept her mother or, as a result of her mother, herself. A long, drawn out scene would hardly capture the same, knife’s-edge force.

A writer can also, according to Genette, manipulate frequency. Here, some algebraic-looking letters: In life, an event happens (n) times, (n) being any number between zero and in perpetuity. Of course, the writer may choose to narrate an event more or less frequently than (n), each of these choices bearing significant effects; In William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, the same events are narrated four times, in each instance through the lens of a different narrator. Other times, as in the above Lydia Davis story, multiple distinct events (i.e. the mother’s frequent nagging) are narrated in a fell swoop, indicating habit. In still other instances, something that doesn’t happen at all is narrated in a hypothetical mode. In an even stranger variation, something that happens once might be told multiple times by the same narrator; Grace Paley’s “Mother,” comes to mind, in which the titular mother dies twice, once halfway through the story and a second time at the end, in order to emphasize the narrator’s grief and regret surrounding the mother’s death.

A writer can also, according to Genette, manipulate frequency. Here, some algebraic-looking letters: In life, an event happens (n) times, (n) being any number between zero and in perpetuity. Of course, the writer may choose to narrate an event more or less frequently than (n), each of these choices bearing significant effects; In William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, the same events are narrated four times, in each instance through the lens of a different narrator. Other times, as in the above Lydia Davis story, multiple distinct events (i.e. the mother’s frequent nagging) are narrated in a fell swoop, indicating habit. In still other instances, something that doesn’t happen at all is narrated in a hypothetical mode. In an even stranger variation, something that happens once might be told multiple times by the same narrator; Grace Paley’s “Mother,” comes to mind, in which the titular mother dies twice, once halfway through the story and a second time at the end, in order to emphasize the narrator’s grief and regret surrounding the mother’s death.

To Genette’s list, I might add “gaps,” the domain of narratologist Meir Sternberg and generally understood by writers as “white space,” or “omissions,” that is, the “stuff left out.”

In attending to time, the writer naturally addresses other elements of craft, such as plot and conflict. The arrangement of events and the speed and ease at which we move through them determine the reader’s experience of those events, what Steinberg terms “suspense, curiosity, and surprise.” What is not addressed by time is easily covered under the domain of space: of course this includes the setting and characters in the story, which naturally gives way to thoughts about point of view, voice, dialogue, tone and mood, the goal of which are often mimetic, aimed at creating Roland Barthes idea of a “realistic effect.” The unit of composition here is the detail, or if you prefer, the image, which is primarily a matter of distance.

How close are we? This is a function of point of view. What can we see, smell, hear, feel, and taste? I prefer detail to image, only because image tends to imply that the visual is the primary sense. Moreover, how large is the space? By this, I am not merely describing setting as filtered through a point of view, but the space of the story itself as an imagined thing. When the reader is lingering over the story later, as is the hope of any writer, how does the story expand into three dimensions in the headspace of that reader? How many rooms are there, if there are rooms at all?

Space is a function primarily and necessarily rooted in language. For this, I turn to Richard Hugo’s The Triggering Town, in which he discusses the difference between private and public poets.

Space is a function primarily and necessarily rooted in language. For this, I turn to Richard Hugo’s The Triggering Town, in which he discusses the difference between private and public poets.

The distinction lies in the relation of the poet to the language. With the public poet the intellectual and emotional contents of the words are the same for the reader as they are for the writer. With the private poet, and most good poets of the last century or so have been private poets, the words, at least certain key words, mean something to the poet they don’t mean to the reader.

He goes on to say that, “The reason this distinction doesn’t hold, of course, is that the majority of words in any poem are public—that is, they mean the same to writer and reader.”

Of course, this cannot be the case. I think often about this distinction when teaching fiction writers how to create the space of a story through the narrator’s voice (we are, in effect, occupying the space of the narrator’s head, especially in first-person or close third-person fiction). The writer Charles Baxter once gave me the advice not to try to approximate “voiciness” on the page through common spoken tics—colloquialisms of generic nature, or syntaxes meant to sound “speechy.” The advice holds. All good writers are interested in voice, even ones as distinctly different in style as Jamaica Kincaid and George Saunders. What holds their disparate approaches together is that the voices are Hugo’s private voices; the reader understands each word for its denotative meaning, of course, but as Hugo describes, the language bears the mark of living off the page, which in turn allows the characters to feel three-dimensional in the mind of the reader. We call such characters round rather than flat, which means they live with us; they take up space.

I return again to the question of how this notion can be of practical application to the writer. If I must take anything from Einstein’s theory, it is that everything is relative to a degree, which suggests to me that the failure of all advice about craft is its willingness to prescribe, and it is this very prescriptiveness that works fresh writers into a tizzy; there are too many rules to follow. I would suggest then, that the only two questions we need to ask ourselves are: Where are we headed, and how quickly or directly would we like to get there?

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.