Here are six notable books of poetry publishing in February.

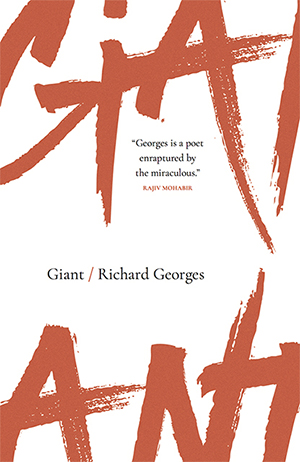

Giant by Richard Georges

Giant begins with how the “gods of our fathers rose” from the “unlighted deep.” The ocean “splashed about their groaning limbs, / foaming and licking their creaking bodies / stippled with black barnacle.” The long titular poem that opens the collection unfolds into a stanza of direct address: “Recite the prayers your mother taught you, / measure the depth of your days in sunsets, / count your crosses, the number of your years.” Georges commands a voice both calming and cleansing. Giant is a book of myths and minutiae. In poems like “Brandywine/Tortola,” narrators long for the old music of youth. The past often opens through the night, when “the ghosts / howl the unreasonableness of love // to those, like me, who listen for voices / on the wind.” These narrators wish “to believe again in gods, // and bodies as real as this green earth is.” Night, wind, prayer, and water become his refrain, coupled with a stubborn belief in words: “This is a night full of voices: / the infant wailing at the baptismal font, / the weeping around a silent casket. / The whole damn world is alight / and hungry and nothing is ever enough— / but there is poetry, which will suffice.”

Virgin by Analicia Sotelo

Virgin by Analicia Sotelo

Sotelo’s poetry reveals the weight of desire, how our hearts drag our bodies. After a narrator heads home from a bar, alone, she’s “discovered / humiliation is physically painful: / the crown-like stigmata of a peach / that’s been twisted, pulled open, / left there.” A later narrator contemplates the “darkness of marriage, // the burial of my preferences / before they can even be born.” In “Trauma with White Agnostic Male,” she writes “This is blood / for blood, a prodigal heartbreak // I must return” (in Sotelo’s poems, past is always present). “I’m Trying to Write a Poem about a Virgin and It’s Awful” is hilarious—“She was very unhappy and vaguely religious so I put her / at the edge of the lake where the ducks were waddling / along like Victorian children, living out their lives in / blithe, downy softness”—and builds toward an emotional end. Imbued with Catholic cultural touches (“I was a clever rosary”), Sotelo mines the Marian paradox with complexity, grace, and power. And this is a book about Texas, where “there’s no winter,” but “the light changes, grows sharper, // keener, and when I was a girl, / it was breath to me, // walking up the hillside to school, / the wind touching my throat.” Her narrators want more out of life, but they clench what they have—and draw us back to her pages. A significant debut.

The Möbius Strip Club of Grief by Bianca Stone

The Möbius Strip Club of Grief by Bianca Stone

“No one here is glad anyone is dead. But / there is a certain comfort in knowing / the dead can entertain us, if we wish.” A little bit Inferno, but maybe even more so the deliciously devilish No Exit, Stone’s book is a strange, entertaining journey into an underground world where poor souls are “clinging to our tragedies, finding our favorite face.” Stone offers her reader a topography of a purgatory, a place where you “leave your inhibitions at the door,” and there’s “Grandma, half-blind, naked but for an open / XL flannel and Birkenstocks.” After their shift, dancers give tips to the House Mom, and then they go upstairs to their rooms, where grief “read itself aloud / in gilt fragments and tapestries fallen apart.” For all the spectacle of this netherworld, this grief returns in waves: “I can’t tell anymore whether I am grieving you particularly / or I simply find life and death erroneous.” You’ve never quite seen a poetic party like this: “Death’s last-minute cosmetic surgery, the skin taut / from gravity, confined in beauty for one last hurrah.” Yet at some point in Stone’s vision, the nightmare recedes, and we settle into her narrator’s mind—one pained by the cycles of generational loss, longing for her mother. When Stone finally returns us to that club in the book’s final pages, it is as if we might never leave there ourselves.

The Elegies of Maximianus translated by A.M. Juster

The Elegies of Maximianus translated by A.M. Juster

“I am not who I was, my greatest part has perished.” Juster’s fluid, engaging translation should bring the curious elegies of Maximianus—whose only previous English edition was in 1900—to a wider audience. A 6th-century Roman poet, Maximianus’s 686 lines arrive in the voice of a “querulous old man” (to quote Michael Roberts’s fine introduction), who laments the loss of his erotic misadventures. Readers of Michel de Montaigne will recognize the poet’s pithy lines quoted in the French essayist’s work (“Alas! how little of life is left to the old.” is crisply rendered by Juster as “how much life remains for old men?”). Juster imbues a profluence to the elegist’s consideration of life. Young Maximianus, full of lust, equally brimmed with folly: “So I, who everyone considered a grave saint, / am wretched and revealed by my own vice.” We can sense his old soul inaccurately lighting the lost loves of his youth—Juster’s translation is sharp, his pacing pure—and the book’s final elegy, a mere dozen lines, arrives with a particular sadness: “Death’s journey is the same for all; the type of life / and exit, though, is not the same for all.” Sometimes there is no solace, not even in memories.

Noirmania by Joanna Novak

Noirmania by Joanna Novak

Joyelle McSweeney has called the necropastoral the “manifestation of the infectiousness, anxiety, and contagion occultly present in the hygienic borders of the classic pastoral.” The necropastoral is a place of “strange meetings,” and it is within that setting Joanna Novak’s Noirmania exists. A dark book with drifting, spaced lines, Noirmania is a series of single-page, untitled poems that depict the stratification of memory. The narrator exists out of time, moving between visions of childhood and a place more severe and stagnant than Theodore Roethke’s root cellar. Sharp lines sneak through: “Who hasn’t / eaten alone at dusk, with the moon / pouring out like a placemat?” While it will take time for readers to settle into Novak’s schema, once they do, there is much to see in the darkness, where “silence studied / my lostness: a mass in a room in a suite / off an impossible house with bats and eaves.”

House of Fact, House of Ruin by Tom Sleigh

House of Fact, House of Ruin by Tom Sleigh

Poet as reporter, reporter as poet. In Sleigh’s essay collection, The Land Between Two Rivers, he ponders the differences between American and Iraqi poetry. He sees the poets Naseer Hassan and Hamed al-Maliki as championing “the Rilkean attributes of vision, inspiration, and the ability to express profound feeling,” in contrast to the occasional “poetry gloom” he feels in the states—born from “the world of workshops, ‘scenes,’ and hyperbolic blurbs.” Sleigh’s new poetry collection is informed by his reporting on the lives of refugees, but it is instructive to see the difference between his modes of writing and seeing. In “Lizards,” an early poem from the book, he is patient: “In the desert the lizard is the only liquid flowing under rocks and / down into crevices, undulating in shadows.” Above the lizard, “in heatwaves turning into air,” the mirage—or perhaps the reality—of tanks appear. Around them “mosques broadcasting wails of static, / baffled minarets like letters of secret code, a whole codex of holiness / and banalities.” The lizards go on, with their “still, flat eyes.” Around them, “marked in red, are the circled oil fields, the blow-torch / refinery flames / looking like souls in illuminated manuscripts.” What Sleigh helps us see in these poems is something deeper than journalism can offer: a heart and mind torn by inhabiting a world but not fully grasping its pain. “Whatever you do,” he writes, “there are rockets falling, / and after the rockets, smoke climbing.” Weeds swallow “beds of lettuces and coddled flowers.” What happens when “the bricked-in hours of the human have all been knocked down”?