In the wake of Carrie Fisher’s death following an in-flight heart attack last year, she left the last of 15 books, The Princess Diarist. The book deals, perhaps fittingly, with the cultural events that first made her famous—the filming of the original Star Wars and the relationship she had with her much older co-star, Harrison Ford.

“When I was a young man, Carrie Fisher was the most beautiful creature I had ever seen,” Steve Martin tweeted the day of her death. “She turned out to be bright and witty as well.” Martin caught some heat about his wording, and eventually deleted his tweet. But the same basic sentiment was there in a number of industry tributes: the journey from the highly sexualized, urgently sought starlet to distinguished afterthought, which seems to happen, for women in film, in the blink of an eye. Fisher deals with this issue in the book, when she discusses the hordes men who confessed to her that they masturbated to her in Star Wars. “If I’d known about all the masturbating I would generate…let’s just say I have mixed feelings. Why did all these men find it so easy to be in love with me then and so complex to be in love with me now?”

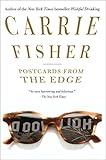

The Princess Diarist can be read as, in effect, a postcard from being a young working actress—but now reads more as an ambivalent missive we are perhaps in a better place to understand a year after its author’s own death. In some ways the book treads familiar ground for readers of Fisher. Ever since she published Postcards from the Edge (1987) she has been known for semi-autobiographical works (first fiction, then increasingly, memoir) which are simultaneously edgy and cozy. Fisher seemed to defy F. Scott Fitzgerald’s stricture that there are no second acts in American lives. Her reinvention of herself as a sober role model and an accomplished writer seemed to promise all kinds of happy endings for mankind, and maybe womankind in particular. Her death at 60 with cocaine, morphine, and ecstasy in her system complicated that rosy picture, as does this final book.

The Princess Diarist can be read as, in effect, a postcard from being a young working actress—but now reads more as an ambivalent missive we are perhaps in a better place to understand a year after its author’s own death. In some ways the book treads familiar ground for readers of Fisher. Ever since she published Postcards from the Edge (1987) she has been known for semi-autobiographical works (first fiction, then increasingly, memoir) which are simultaneously edgy and cozy. Fisher seemed to defy F. Scott Fitzgerald’s stricture that there are no second acts in American lives. Her reinvention of herself as a sober role model and an accomplished writer seemed to promise all kinds of happy endings for mankind, and maybe womankind in particular. Her death at 60 with cocaine, morphine, and ecstasy in her system complicated that rosy picture, as does this final book.

There is a strong undercurrent of sorrow and anger in The Princess Diarist, her seventh memoir. The meat of the book is Fisher’s secret (at the time of publication) relationship with Harrison Ford, her married and 14-year-senior costar on the original Star Wars film and its sequels. But despite this detail, at first the book doesn’t seem that far outside of Fisher’s usual wheelhouse. After all, part of her allure as a writer has always been her backstage access. Ever the thoughtful hostess, she takes us with his on her adventures with celebrities and drugs, without ever really challenging our preconceptions. After all, when you were cradled in the tabloid scandal of the century (Eddie Fisher leaving her mother, Debbie Reynolds, for Elizabeth Taylor) nothing’s shocking, and Fisher’s jaded wit has always been the armor in which she presented her prose. In The Princess Diarist one senses Fisher had allowed herself, for the first time, to let us feel her experience, not just the comic anecdote of it.

At first this seems like the regular stuff of Hollywood memoir. Now it can be told! Famous liaison never before revealed! The Princess Diarist also contains elements of what we’ve come to expect from the Fisher oeuvre: anecdotes about Warren Beatty getting consulted about whether she should wear a bra on Shampoo, her first film (a casual no), bookended by George Lucas’s odd stricture that she should not wear one in Star Wars because there’s no underwear in space, for the simple (?) reason that a bra could strangle you there. These zippy stories were widely quoted in reviews and memes even after her death—because they were fun, mildly risqué but not too challenging, involving famous and beloved figures and films. Anyone reading quickly, say for a hot take immediately following release, could be forgiven for only picking up on these superficial aspects of the book.

The month before Fisher died, reviewers responded to a ghost book, the one that was mainly there in outline, in the imagination of its beholder. If they found themselves discomfited by parts that did not fit, they pinned the blame squarely on Fisher for a less than slick execution of what they’d come to expect. J.D. Biersdorfer of The New York Times asks “whether anyone cares about the dalliance four decades later.” A year later, reviewing the paperback edition, Barbara Ellen asserts in The Guardian that Harrison Ford “comes across as an emotionally distant crashing bore.”

I too struggled with The Princess Diarist just after Fisher’s death. There was something unexpected—hell, downright unsettling here. I lent the book to several friends and they all returned it to me, eyes more or less averted, saying, “Thanks, I guess…not sure what to make of that.”

I’ve only encountered one reviewer willing to acknowledge the dangerous nature of the book. Tasha Robinson, writing a few days after Fisher’s death, admits she feels “alarm and empathy,” and calls it “weird and dysfunctional how the media has represented their brief relationship as the giddy confirmation of a collective fandom fantasy, rather than the way Fisher actually presents it, as exhausting and gutting.” Robinson brings her attention to what should, conventionally, be the most giddy scene—the start of the affair with her costar. Instead, it is one of the more disturbing moments of the book, prescient when it comes to what we came to know in 2017.

The heart of this book is the three notebooks she kept while filming Star Wars and dealing with her remote, manipulative lover and costar. Fisher found the notebooks under the floorboards of her living room when she began an extensive renovation. From them we first learn the reason Fisher feigned enthusiastic support for the Dutch donut hairdo that was to haunt her the rest of her life: she had been ordered to lose 10 pounds and sent to a fat farm in Arizona, but had failed to subtract herself the contractually stipulated amount, and thus was terrified she would be fired. Therefore she wanted to appear especially game regarding the Dutch girl braids. This need to appear game turns out to be the key to the whole Harrison Ford affair, which begins under an inebriated, faintly violent cloud.

On a Friday night a few weeks into filming, the almost entirely male crew threw a surprise birthday party for George Lucas. They ply the inexperienced 19-year-old Carrie Fisher with drinks, even though she tells them she’s allergic.

The male crew talk about how they wish they were somewhere where finding sexually compliant partners was more convenient, “on the coast someplace where the locals are ready and willing.”

Fisher explicitly states that at this point she has never really drank or taken drugs. She’s drinking lukewarm coke when the crew decides to get her drunk. They start insisting she drink, and, wanting to fit in and be friendly, she’s soon very drunk. The scene gets a little scary, the men vying with each other for who is going to whisk her off. Then, as if on cue, in steps Harrison Ford to save the day, or rather, to initiate a demoralizing and ultimately destructive sexual relationship with his much younger colleague. He’s married, with young children, with no desire to undo those things, something that tortures Fisher during the course of their relationship.

“[T]here was also an element of danger,” she writes. “Not with a capital ‘D,’ but the word in whatever form applies due to the roughhousing that seemed to rule the day, or the roost, or the world.”

There is a lot going on here. Fisher, working against her tendency to gloss over and glide manically, draws the scene out. This is clearly an experience that has troubled her for more than half a lifetime, though in the pre-Harvey Weinstein era she hesitates, and parses her words. On set, she still struggled to appear “somewhere between sophisticated and louche—someone you’d think had gone to boarding school in Switzerland with Anjelica Huston and had learned to speak four languages, including Portuguese,” but the reality was that Fisher is very inexperienced and had only had one boyfriend, in drama school the previous year.

To be clear: on the Matt Damon scale of sexual harassment (in which anything less than rape doesn’t count), what is described in The Princess Diarist does not register. But Fisher, to her credit, allows her 19-year-old self to state her case. Not only does she allow that inexperienced, but talented and ambitious girl, her own words, but she also chews on them herself from her perspective 40 years later. Her verdict: that dismal sexual experience helped form the template for a life marked by mental instability and drug abuse, as well as her voice as a writer. Ford contributed to both by keeping her high on his never-ending supply of potent weed, by preying on her when she was inebriated at the forceful urging of the all male crew, and by being so inaccessible that she turned to her notebooks for company.

Those notebooks form the heart of this book, which, to this reader, is paradoxically her most alive—uncomfortable, uneven, yes—but also raw.

I recently had a conversation with my mother-in-law about this moment of reckoning in our culture vis-à-vis sexual harassment, and more broadly, the treatment of women. While sympathetic, she couldn’t understand why “these women are dredging up stories from 30 years ago.” In response, I show her this book—a hologram from 1976 with Fisher’s 19-year-old person intact, delivering her urgent message from a galaxy not so far away.