1.

In August, my family traveled to Kansas to be in the path of totality for the eclipse. We decided to watch from a farm on the Platte River. My husband, Nick, and I would be traveling from Connecticut with my parents; our two-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Thea; and seven-month-old son, Simon, so a reasonable flight and proximity to a major airport seemed logistically important. Of more inarticulable importance, though, is that Kansas City is at the center of our many Venn diagrams making up home. My parents met and married in Kansas City. My cousins grew up in central Kansas. Generations ago, and decades before the families had any reason to know one another, my mom’s people and my dad’s people criss-crossed one another in waves of migration from Appalachia across the plains.

Nick is a high school physics teacher with a Ph.D. in astronomy. At one time, Nick and his graduate school adviser searched the Southern Hemisphere for lensed quasars (mirages where gravity bends light in predictable ways that allow astrophysicists determine the age of the universe). Nine years into his teaching career, Nick’s adviser asked if he would help search for more. After almost two years of work, Nick was second author on a paper presenting their first lensed quasar discoveries, helping, in this small way, to tell the story of our universe in between days filled with life’s work—grading physics homework assignments and potty training our toddler. His institutional affiliation reads: “Staples High School, Westport, Connecticut.”

2.

My parents and I lived in Leawood, Kan., (just outside of Kansas City) until I was six. I spent long, sunny summer weeks with both sets of grandparents, riding on Pa’s tractor, snuggled on Baba’s lap listening to stories, and fishing in central Missouri with Grandfather and reading book after book with Grandmother. Then, in 2011, I started working on a novel set in a fictional southeast Kansas. I’d been to Atchison to visit the Amelia Earhart museum and had been thinking for a long time about the stately homes on a hill overlooking the Platte River and how the steep cliff drop, so unlike what I’d expected to find on a river in the plains, to the muddy water below seemed to viscerally mirror the alluring and unsettling unknowns in Earhart’s disappearance. I wrote the novel mostly in caffeine-fueled delirious hours between four and six in the morning before I went to my job teaching high school English.

When I first started working on the novel, Nick and I had just met. The novel was about Amelia, a high school student named for Earhart, trying to decide if the truest, best thing for her to do was to leave (something her mother and her grandmother had never been able to) or stay in her hometown. I’d been thinking about how leaving the familiar is often presented as an heroic necessity, a foil to a pathetic martyr figure who stays out of a boring and frightened sense of duty. But I had been wondering if home wasn’t sometimes just as hard, important, heroic in its own non-martyrish way. One of many problems with the novel is that I’m still not entirely sure how to make clear the forces that made Amelia feel she needed to stay. The reasons she might give appear small or even mundane: a loyalty to her mother, fear of being responsible for a boyfriend’s demise. But these kind of fears are also big; these quiet, individual decisions add up to make a life.

3.

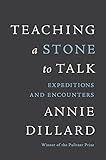

When I taught high school, I often assigned essays from Annie Dillard’s Teaching a Stone to Talk. I must have read “Total Eclipse” many times, but I re-read it in the summer of 2017 with a new and self-absorbed fascination. When The Atlantic reprinted the essay in August, the pull quote was Dillard’s declaration that “seeing a partial eclipse bears the same relation to seeing a total eclipse as kissing a man does to marrying him.” When we were planning our trip, Nick had explained to us that even one percent visibility would mean enough light that the sky would only appear dusky because the sun is so much brighter than the moon. In the path of totality, though, we might see the corona, a halo of the sun’s visible atmosphere. Dillard’s description of the emotional disorientation of the eclipse sparked something I was giddy to experience. Dillard writes:

When I taught high school, I often assigned essays from Annie Dillard’s Teaching a Stone to Talk. I must have read “Total Eclipse” many times, but I re-read it in the summer of 2017 with a new and self-absorbed fascination. When The Atlantic reprinted the essay in August, the pull quote was Dillard’s declaration that “seeing a partial eclipse bears the same relation to seeing a total eclipse as kissing a man does to marrying him.” When we were planning our trip, Nick had explained to us that even one percent visibility would mean enough light that the sky would only appear dusky because the sun is so much brighter than the moon. In the path of totality, though, we might see the corona, a halo of the sun’s visible atmosphere. Dillard’s description of the emotional disorientation of the eclipse sparked something I was giddy to experience. Dillard writes:

If I had not read that it was the moon, I could have seen the sight a hundred times and never thought of the moon once. (If, however, I had not read that it was the moon—if, like most of the world’s people throughout time, I had simply glanced up and seen this thing—then I doubtless would not have speculated much, but would have, like Emperor Louis of Bavaria in 840, simply died of fright on the spot.)

In the days leading up to our trip, I included this final detail in every conversation about what we might see in Kansas.

On our drive from the airport to the farm, I’d looked hopefully at the satellite weather report on my phone, but as the moments of totality neared, the patchy cloud cover I’d been willfully ignoring grew thicker, stretching to the horizon in every direction. We would not see the moon eclipse the sun.

About 30 seconds before totality, Simon woke up crying. I pulled his stroller over to the long, uneven farm grass, under a tent that had been set up to cover the concession stand. In spite of the all the publicity for the eclipse, the scene on the farm felt like a backyard picnic my Pa would have approved of. Simon was wide awake and his cry sounded frantic—scared and insistent, not one I’d come to recognize from his usual needs—so I scooped him up and held him in my arms. It started to rain hard in the way I remember from Midwestern late afternoons in my childhood. This rain smelled like humidity trapped in the Great Plains and Kansas grass and farms. From under the tent, I watched the sky get dark—darker than even Dillard’s essay had prepared me for—but mostly I watched the people watching the sky. When totality began, a recording told us it was safe to take off our glasses. People chuckled good-naturedly; we hadn’t been able to see the sun at all in some time. The grade school-aged grandchildren of the farmers who had been busy starting an abandoned tractor with a screwdriver became still. We couldn’t see what was happening, but still everyone stopped and watched the sky in the rain. Thea stood between my parents and Nick, all of their eyes turned upward. Two minutes and 38 seconds later, the recording said, “Totality Ending. Glasses on. Glasses on.” Everyone laughed again. Standing a bit apart from the rest of my family, I held Simon close and watched Nick hug each of my parents. He didn’t look disappointed but grateful. When we were planning the trip, I imagined the experience would be enormous, dramatic, violent even. Instead it was intimate.

I walked out from under the tent so we could make our way to the car. In Dillard’s essay, she describes how quickly, fearfully even, the eclipse-watchers fled the places they’d sought out to watch the event: “[W]e never looked back. It was a general vamoose, and an odd one, for when we left the hill, the sun was still partially eclipsed—a sight rare enough, and one which, in itself, we would probably have driven five hours to see.”

Even as we were leaving the farm, everyone was talking about the 2024 eclipse. Hidden from our view by the clouds, the moon’s shadow had rushed toward us at around 1,700 miles an hour. We’d been awed despite what we’d missed; what was seven years to wait for a chance to see it again? I turned 35 the morning after the eclipse and thought as I sometimes do about how strange it is to feel like the exact same little girl who spent summers running around on long Kansas grass, and at the same time to have lived almost—if I’m lucky—half my life already.

Somehow, for all the times I’d read Dillard’s essay, I’d never understood how deeply she connects the eclipse to mortality. “It had been like dying,” she begins. “It had been like the death of someone, irrational, that sliding down the mountain pass, and into the region of dread.” No matter how rationally we can understand the fact of an eclipse, the experience of the sun disappearing midday is a visceral reminder of “what our sciences cannot locate or name…our complex and inexplicable caring for each other, and for our life together here.”

4.

When I was pregnant with Thea, I set her due date as my writing deadline: finish a draft of my novel, even if it was horrible, before I went into labor. I did. In those early months of sleep-deprived parenthood, the novel sat in the top drawer of my desk. When I was starting to pick back up the pieces of my pre-motherhood self, I went on an easy run around our neighborhood, and then I started writing in my journal. I revised some old essays, went back to work, trained for a half marathon, but still the novel sat in my drawer.

Last summer, pregnant with my son, I took the manuscript out. Some of the things I remembered being very bad really were very bad. But there were some sentences I really liked. And some ideas I really liked. I wrote a new section, from Amelia’s mother’s point of view. The novel had always been about women, but I realized it might become a story about mothers and daughters. I liked thinking that the reason I hadn’t been able to sit down and revise it was because it really wasn’t done yet. I had a new perspective and story to tell.

When we’re back visiting Kansas City, I find myself drawn to two distinct layers of family history. First I see the younger version of my parents, stories I’ve heard, old houses we’ve driven past, family lore from their childhoods. I can imagine my mom driving through Kansas’s Flint Hills on her way from her law school apartment in Lawrence to her parents’ home in central Kansas, my dad and my uncle playing baseball in the railroad towns in Missouri. I know the stories I’m conjuring are inaccurate, warped by the limits any child has of understanding her parents as adults separate from parenthood, but still this past generation feels only just out of reach. The other current that runs through the land out our car window is more vague, romantic, eerie.

My mom has spent the past two decades digging deeper and deeper into our genealogy, and so often family trips have included a detour to the Providence Historical Society or, once, a cemetery on the outskirts of a farm in unincorporated Randolph County, Mo. Genealogy was appealing to the former attorney in her. She told me she liked the research, the sense of progress, the communities of disparate and cooperative strangers sharing scans of birth certificates and hunches about names whose spellings had been changed.

Thea’s middle name is Louise, after both my dad’s mom and my own mom, who themselves were named for other Louises. Not long after Thea was born, I signed up for my own Ancestry.com account. I’d been thinking a lot about generations of Louises who’d become mothers before me, and I’d also been fascinated by wondering what my daughter had inherited from me and from my husband. I pored through the decades of work my mom had done, branches off of branches on my family tree, names repeated, predictably at first and then less conventionally. Louises in New England port cities, Louises farming in Appalachia, Louises in Central Missouri, Louises traveling west through Kansas. Louises passing down stories.

I had this idea that going back to Kansas to see the eclipse would give me some sort of clarity about the future of this project. Should I finish the novel?

Instead of finding clarity specific to my novel, I felt something only tangentially related to my writing. I felt a little proud and a little less embarrassed to be carving out time to write instead of being “a real writer” (whatever that might mean). The legacy of carving out time, like Nick does in his search for lensed quasars, came to feel like part of the same bigger project. In this work, we are connected to the quiet, intimate work of the amateurs (genealogists, storytellers, astronomers) who preceded us.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.