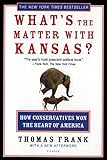

To write books about Kansas as a Kansan, is, to some extent, to write without precedent. Evan S. Connell’s middle-class Kansas City drawing rooms and Laura Ingalls Wilder’s virgin prairie haven’t existed for a lifetime or two. More recent books have tended to turn Kansas into a metaphor for the country (Thomas Frank’s What’s the Matter with Kansas?), dive deep into the minutia of local history (William Least Heat-Moon’s history of Chase County, PrairyErth), or take a form unlikely to reach readers without subscriptions to The New Yorker (Antonya Nelson’s short stories, sometimes set in and around Wichita).

To write books about Kansas as a Kansan, is, to some extent, to write without precedent. Evan S. Connell’s middle-class Kansas City drawing rooms and Laura Ingalls Wilder’s virgin prairie haven’t existed for a lifetime or two. More recent books have tended to turn Kansas into a metaphor for the country (Thomas Frank’s What’s the Matter with Kansas?), dive deep into the minutia of local history (William Least Heat-Moon’s history of Chase County, PrairyErth), or take a form unlikely to reach readers without subscriptions to The New Yorker (Antonya Nelson’s short stories, sometimes set in and around Wichita).

In this vacuum, who was a budding young Kansas writer to look to for guidance and examples? For decades, the answer was no one. It was as if some Kansas Tinkerbell had ceased to inspire readers’ imaginations and up and died.

And yet somehow the state is experiencing a literary renaissance (read another account of the state’s possibilities for writers here at The Millions).

Five books of fiction and two memoirs set in Kansas have been published in the last few years or are forthcoming soon—by writers who were born or raised in Kansans. (My own Kansas story about love, meth, and anhydrous ammonia was included in Best American Mystery Stories 2016.) The characters in these books buck up against religion, politics, drugs, guns and wild hare ideas. If there is a running theme in these books, it’s that the characters are trying to figure out who they have become while no one is paying attention.

Here are the writers at the heart of the new Kansas literature.

Farooq Ahmed

Kansas has a long, complex history with race and religion. In the years before the Civil War, the preacher Henry Ward Beecher famously sent rifles to anti-slavery factions within the state in boxes marked Bibles. Yet today Secretary of State Kris Kobach has become the leading figure in a national movement to enact voter ID laws that target Democratic-leaning black and brown voters and laws designed to harass undocumented immigrants into “self-deporting.” Ahmed’s novel Kansastan, just announced as forthcoming in 2019, is set in the middle of this tension. It takes place in a new-future revival of the border war, with a young Muslim boy plotting to take over his mosque and lead his parishioners into battle against Missouri.

Technically, Barnett grew up in Kansas City, Missouri, but the fortunes of the two Kansas Cities have always been intertwined. In her novel Jam on the Vine, Barnett offers a riveting and eye-opening view of the city, as seen by Ivoe Williams, a journalist who moves to Kansas City from Texas to work at a newspaper modeled after Kansas City’s real-life black paper The Call. Ivoe reports on prison abuses and lynchings in a story that reveals how Kansas City’s problems with public schools, housing, and other civic institutions are the lingering symptoms of a persistent systemic racism.

As a 26-year-old public defender in Brooklyn, McDermott became convinced he was being secretly filmed for a TV show, a bipolar episode that would eventually lead to his hospitalization and return to Wichita to live with his mother. In his memoir The Gorilla and the Bird, he tells the story of his recovery and his family’s complex relationship with psychiatric illness and drug abuse. It’s a personal history that conflates with a larger one. For years, the state’s criminally-insane were locked up in the Larned Correctional Mental Health Facility while, at the same time, the Menninger Clinic and Sanitorium in Topeka was on the progressive edge of psychiatric treatment. For McDermott, it’s not an institution but his mother who nurses and drags him back to health.

Mandelbaum’s debut collection, Bad Kansas, won the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction, an appropriate award since Mandelbaum shares with O’Connor a taste in characters whose outsized and idiosyncratic traits border on the grotesque. In her story “Bad Bear,” for example, a recent college graduate is escaping her flea-infested apartment by hanging out at Clinton Lake, where she meets a man on a real-life bear hunt. The story hinges on a small piece of dialogue that reflects a neat observation about rural Kansas. The man takes the woman home and says, “This here is some of the only wilderness left in Kansas.” She replies, “I didn’t know Kansas had any wilderness.”

Milward has written two story collections. His most recent, I Was a Revolutionary, tries to make sense of the messy history encapsulated by the John Stuart Curry mural of a Bible-and-rifle wielding John Brown that graces the capital building in Topeka. The stories feature the dreaded William Quantrill, along with the black exodusters who settled towns like Nicodemus and conmen like John R. Brinkley, who convinced men to travel to his “clinic” in Kansas so that he could implant them with goat testicles. All of these threads converge in the title story, about a University of Kansas professor whose past as a member of the Weather Underground gets discovered by his students and conservative media.

Sarah Smarsh

History also plays a role in Sarah Smarsh’s forthcoming memoir, originally titled In the Red but soon to be announced with a new title (see her Year in Reading here). The memoir tells the story of the circuitous path that Smarsh’s family took between small southern Kansas towns and Wichita, eastern Colorado, and Chicago. It’s a story of scarcity and pulling yourself up by your bootstraps only to have those straps yanked away. Smarsh has published essays about economics and class markers such as lack of dental care. That essay, “Poor Teeth,” was long-listed in The Best American Essays 2015.

The undertow of class lurks just beneath the surface in Cote Smith’s Hurt People. Set in Smith’s hometown of Leavenworth, the characters live in the shadows of four prisons, including the maximum-security penitentiary that has housed everyone from James Earl Ray to Michael Vick and was mentioned as a possible new home for the political prisoners at Guantanamo Bay. In the novel, there’s a prison break and also a magnetic stranger who promises two young friends an escape from their cash-strapped lives and uncertain futures. It’s a coming-of-age novel like so many others, except that its set in a place that has never before been the host of such a story.

Image: Wikipedia