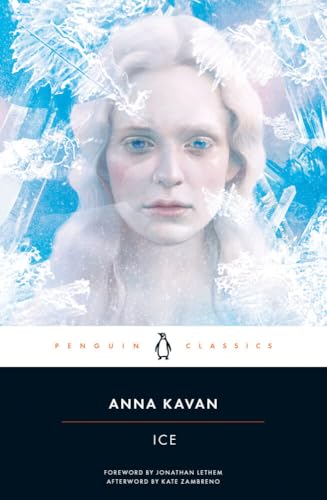

Ice—the last novel Anna Kavan wrote before she was discovered dead with a syringe in her arm and her head resting on the case in which she kept her heroin—is a gem of speculative fiction. It is uncanny, hallucinatory, apocalyptic, a book crowded with glaciers and starlight. The novel’s popularity has grown steadily since its first publication in 1967 and Penguin Classics 50th Anniversary reissue of Ice, with a fine introduction by Jonathan Lethem, gives Kavan’s valedictory effort the platform it deserves.

The plot is deceptively simple. In the aftermath of a major atomic event, a monomaniacal man searches for a fragile, silver-haired girl from his past as the vise of a new ice age clinches the planet. He searches for her through the chaotic territory of memories, dreams, and half-real war zones. At all costs, he must locate “the glass girl” before the world darkens and human life is over. In a game of cat and mouse, he sails to foreign shores on the last overcrowded ships, gleaning clues to her whereabouts, yet when he finds her—and he always manages to—she flees from him as from a tyrant. The warden of an unnamed northern country is the narrator’s erotic rival and has the power and savvy to preempt the narrator’s every move. Kavan makes ample suggestions that the two adversaries are in fact doubles, mirror-images, the Superego and Id of the author’s avowedly psychoanalytical nightmare (Kavan’s best friend and sometime creative collaborator, Karl Theodor Bluth, was a psychoanalyst who treated her depression and supplied her with legal heroin).

In addition to being a prolific writer and inveterate drug addict, Kavan was a serious painter, producing startling artworks in a series of modernist styles, from cubism and expressionism to surrealism. Her wartime traumas (she lost her only son in WWII) and confinement in asylums (much like another oft-neglected English painter and writer, Leonora Carrington) add to Ice’s strange alchemy of glittering, visionary detail and psychological dishevelment. Considering Kavan’s earlier works, such as the story collections Asylum Piece and I Am Lazarus, one can’t help but read the glass girl in Ice as, in part, a self-portrait of the protean, charismatic, and psychologically bruised author who never recovered from a childhood of maternal neglect.

In addition to being a prolific writer and inveterate drug addict, Kavan was a serious painter, producing startling artworks in a series of modernist styles, from cubism and expressionism to surrealism. Her wartime traumas (she lost her only son in WWII) and confinement in asylums (much like another oft-neglected English painter and writer, Leonora Carrington) add to Ice’s strange alchemy of glittering, visionary detail and psychological dishevelment. Considering Kavan’s earlier works, such as the story collections Asylum Piece and I Am Lazarus, one can’t help but read the glass girl in Ice as, in part, a self-portrait of the protean, charismatic, and psychologically bruised author who never recovered from a childhood of maternal neglect.

The novel’s dystopian world is hermetically sealed. Geographical information is withheld and we are never quite able to get our bearings in this landscape of snow and ruins, illuminated by the ever-changing lights of the aura borealis. The glass girl slips through the pages, tantalizingly out of reach, seen through the filter of the male narrator’s objectifying, sadistic, chimerical gaze. Her hair is “bright as spun glass” and “shimmers like silver fire;” her face “cracks to pieces and tumbles into the dark;” the narrator fantasizes about “the circular marks of teeth [standing] out clearly” on her “white flesh;” he sees “the dead moon dance over the icebergs, as it would at the end of our world, while she watches from the tent of her glittering hair;” “mountainous walls of ice surround” the girl and “huge ice-battlements fill…the sky, lit from within by frigid mineral fires.” One never tires of Kavan’s poetry. She has a gift for elemental and atavistic language.

The science fiction writer Brian Aldiss has dubbed Kavan “Kafka’s sister” for good reason. Not only did she absorb and creatively imitate many of Franz Kafka’s short stories in the 1930s and 1940s, but she carried his enthusiasm for the frustrated quest, the skeptical fantasy, and the allegory without a key into her mature work. It’s hard not to see reflections of Kafka’s The Castle and The Trial in Ice. As in those novels, the mysteries of the invisible and all-powerful authorities are never penetrated or understood. Kavan even changed her name from Helen Ferguson in 1939 as a phonetic gesture to Kafka, whose own Czech surname was originally spelled “Kavka.”

The science fiction writer Brian Aldiss has dubbed Kavan “Kafka’s sister” for good reason. Not only did she absorb and creatively imitate many of Franz Kafka’s short stories in the 1930s and 1940s, but she carried his enthusiasm for the frustrated quest, the skeptical fantasy, and the allegory without a key into her mature work. It’s hard not to see reflections of Kafka’s The Castle and The Trial in Ice. As in those novels, the mysteries of the invisible and all-powerful authorities are never penetrated or understood. Kavan even changed her name from Helen Ferguson in 1939 as a phonetic gesture to Kafka, whose own Czech surname was originally spelled “Kavka.”

Some critics read the “ice” as a metaphor for Kavan’s desperate struggle with heroin and the cold, suffocating experience of addiction. Others view the novel as a veiled autobiography of Kavan’s relationships with abusive men that eventually led to romantic abstention. Given that the narrator, the glass girl, and the warden are sometimes conflated through slippages in point of view, one could see the various character dynamics as a kind of alchemical yearning for the androgyne, for the union of psychological, emotional, and sexual opposites (a major preoccupation of surrealists like Max Ernst, whose technical innovations Kavan appropriated in her own paintings). To a certain degree, it’s useful to interpret the book as a critique of totalitarianism, the ecological crimes of the Anthropocene, or a protest against the Cold War. A few have pointed out its proto-feminist verve, though the satire of patriarchal thought-control is never entirely satisfying or aboveboard, as it is, say, in the works of her contemporaries Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath. Kavan’s first critic, Brian Aldiss, saw Ice as a pure science fiction novel. Faced with such a multidimensional work, the reviewer is happy to allow all these interpretative planes to coexist.

Even 50 years after its publication, this is still a relevant book. It’s not perfect. The author, after all, was in and out of the hospital during the process of composition and her editor, Peter Lang, demanded dramatic revisions before agreeing to publish the novel (characterized by one manuscript reader as a “mixture of Kafka and the Avengers,” a description Kavan found delightful). The narrative repetition of chase and escape can be tiresome and the prose can occasionally slip from its usual sterling quality. Nevertheless, Ice is ambitious, unforgettable, and one of a kind. It demands to be experienced. During a time of environmental crisis, when totalitarian-inflected administrations are brazenly withdrawing from climate accords, when ice caps are melting and the world’s magnificent glaciers are disappearing, Ice provides a photographic negative of the present moment—a world overshadowed by atomic threat and nearly devoid of ice.