1.

A lot of fans know Edgar Allan Poe earned just $9 for “The Raven,” now one of the most popular poems of all time, read out loud by schoolteachers the world over. What most people don’t know is that, for his entire oeuvre—all his fiction, poetry, criticism, lectures—Poe earned only about $6,200 in his lifetime, or approximately $191,087 adjusted for inflation.

Maybe $191,087 seems like a lot of money. And sure, as book advances go, that’d be a generous one, the kind that fellow writers would whisper about. But what if $191,087 was all you got for 20 years of work and the stuff you wrote happened to be among the most enduring literature ever produced by anyone anywhere?

In one sense, there could not be a more searing indictment of the supposed rewards of the writing life: how, whether we’re geniuses like Poe or not, we suffer and rewrite and yet never realize anything even kind of approaching a commensurate value.

In another sense, there’s hope for us all.

Last October, in the depths of a depression so profound and overwhelming that I had to take mental-health leave from work, I started rereading Poe for the first time since I was a kid. And something happened: I encountered a writer completely different from the one I thought I knew.

It turned out Poe was not a mysterious, mad genius. He was actually a lot like my writer-friends, with whom I constantly exchange emails bitching about the perversities of our trade—the struggle to break in, the late and sometimes nonexistent payments, the occasional stolen pitch. In short, I realized that Poe was, for a good portion of his career, a broke-ass freelancer. Also, that our much-vaunted gig economy isn’t the new development it’s so often taken to be.

Poe’s short stories weren’t the adventure-horror tales I remembered, either. They turned out to be exquisitely wrought metaphors for despair. In “MS. Found in a Bottle,” the narrator, finding himself just about to be sucked into a whirlpool, says, “It is evident that we are hurrying onwards to some exciting knowledge—some never-to-be-imparted secret, whose attainment is destruction.” I read the line and laughed in recognition. That was 2016 for me, in a sentence. Call it a most immemorial year.

I didn’t know it then, but reevaluating Poe is, in fact, a time-honored tradition. Every generation discovers its own Poe; in the 168 years since his death, the hot takes have just kept coming. R.W.B. Lewis described the phenomenon this way in 1980: “One of the important recurring games of American literary history has been that of revising the received human image of Edgar Allan Poe.”

There are obvious and less obvious reasons for this continual reevaluation. For starters, Poe’s earliest biographies—some of them based on inaccurate information Poe himself provided—needed correcting in a literal sense. Poe’s literary executor Rufus W. Griswold, for whatever reason, forged letters and deliberately torpedoed Poe’s reputation. The inaccuracies and falsehoods weren’t cleared up until almost 100 years after Poe’s death, with Arthur Hobson Quinn’s 1941 biography.

There are obvious and less obvious reasons for this continual reevaluation. For starters, Poe’s earliest biographies—some of them based on inaccurate information Poe himself provided—needed correcting in a literal sense. Poe’s literary executor Rufus W. Griswold, for whatever reason, forged letters and deliberately torpedoed Poe’s reputation. The inaccuracies and falsehoods weren’t cleared up until almost 100 years after Poe’s death, with Arthur Hobson Quinn’s 1941 biography.

Another reason is, well, I’m not the only person to read Poe as a child and again as an adult and to be struck by the differences. In his magnificent Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe, published in 1971, Daniel Hoffman writes, “I really began to read Poe when just emerging from childhood. Then one was entranced by such ideas as secret codes, hypnotism, closed systems of self-consistent thought.” Later, Hoffman says, “Returning to the loci of these pubescent shocks and thrills…I found that there was often a complexity of implication, a plumbing of the abyss of human nature.” Ditto.

You never enter the same Poe whirlpool twice. Much of his work has a purposeful, built-in double nature; he intended we discover “secret codes” of meaning. While Poe despised facile parables, in a review of Nathaniel Hawthorne in 1842, he allowed, “Where the suggested meaning runs through the obvious meaning in a very profound under-current, so as to never interfere with the upper one without our own volition,” such schemes are permissible.

This points to the other important, less acknowledged, double nature of Poe’s work. It’s both art and commercial entertainment. Few other American writers so obviously and continually straddle the gap between high and low culture, between art for art’s sake and commercial enterprise.

Which is why the Poe reevaluation game isn’t just played by academics and highbrows—including Fyodor Dostoevsky, Charles Baudelaire, T.S. Eliot, Richard Wilbur, Allen Tate, Jacques Barzun, and Vladimir Nabokov. Poe is pop, too. The Simpsons, Britney Spears, Roger Corman, an NFL team and romance novelists have all joined in the game. The Beatles put Poe in the top row, eighth from the left, on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, just slightly removed from W.C. Fields and Marilyn Monroe.

I think if Poe hadn’t had to write for money, he’d probably have faded away long ago.

2.

Picture this: A tech breakthrough has made mass publishing cheaper than ever before. With the cost of entry down, new publications launch with much high-flown talk about how they’ll revolutionize journalism, only to shut their doors a few years or even months later. Because the industry is so unstable, editors and writers are caught in a revolving door of hirings, firings, and layoffs. A handful of the players become rich and famous, but few of them are freelance writers, for whom rates remain scandalously low. Though some publications pay contributors on a sliding scale according to the popularity of their work, it’s mostly the case that writers don’t earn a penny more than their original fee even when their work goes viral.

I’m speaking of Poe’s time, not our own. Still, I expect some of this will sound familiar. Pretty much the only piece missing is a pivot to video.

Here’s something else that might sound familiar. Poe grew up writing moony, ponderous poetry and dreaming of literary stardom. Surely, he figured, the world would recognize his genius—the critics would rave, the angels would sing!

The problem was he had no trust fund, no private means. Poe had been more or less disowned by his wealthy adoptive father John Allan, who would eventually leave Poe out of his will altogether. All of this meant, then as now, that Poe had to compromise his cherished ideals and buckle down to the realities of the marketplace.

He would hold a series of short-lived and ill-paid editorial jobs, beginning with the Southern Literary Messenger, Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, Graham’s Magazine, and, finally, the New York Evening Mirror and the Broadway Journal. In between and after these jobs, he’d be what John Ward Ostrom called a “literary entrepreneur,” i.e., a broke-ass freelancer.

As Michael Allen laid out in 1969’s Poe and the British Magazine Tradition, the story of Poe’s career is in large part the story of a writer struggling to adapt to the demands of a mass audience. His earliest literary friends and mentors had “turned him to drudging upon whatever may make money” (John Pendleton Kennedy) and advised him to “lower himself a little to the ordinary comprehension of the generality of readers” (James Kirke Paulding).

Meanwhile the stakes were as high as stakes go. It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that if Poe didn’t write pieces he could sell, he and his family didn’t eat. Poe’s one-time boss George Graham described him wandering “from publisher to publisher, with his print-like manuscript, scrupulously clean and neatly rolled” yet finding “no market for his brain” and “with despair at heart, misery ahead for himself and his loved ones, and gaunt famine dogging at his heel.”

At one point, when Poe was ill, his mother-in-law and aunt Maria Clemm was forced to do all this on Poe’s behalf: “Going about from place to place, in the bitter weather, half-starved and thinly clad, with a poem or some other literary article she was striving to sell…begging for him and his poor partner, both being in want of the commonest necessities of life.” I’ve heard some freelance horror stories in my time, but this one takes the Palme d’Or.

Even when Poe did manage to sell his literary wares, he didn’t earn very much, as this chart I assembled shows. Over time, he did his fitful best to make his art commercial; he simplified his language and tried his hand at popular forms. Some of these experiments worked and some didn’t. Poe still wrote “in a style too much above the popular level to be well paid,” as his editor-friend N.P. Willis put it.

Why? The usual reasons, as I see it. A writer’s heart wants what it wants. It’s not at all a simple matter to ditch the obsessions that drive you to write to begin with, and it’s hard to change your natural register, no matter that commonplace comment in MFA programs, Maybe I’ll just write a romance novel for money. If it really were so easy to write popular stuff, wouldn’t we all be churning out viral articles and paying the rent with royalties from our bestselling YA werewolf romances? In between writing prose that makes the Nobel people tremble, I mean.

| Piece | Year Published | Original Payment | Approx. Amount in 2017 Dollars |

| “Ligeia” | 1838 | $10 | $253 |

| “The Haunted Palace” | 1839 | $5 | $127 |

| “The Fall of the House of Usher” | 1839 | $24 | $609 |

| “The Man of the Crowd” | 1840 | $16 | $431 |

| “The Masque of the Red Death” | 1842 | $12 | $345 |

| “The Pit and the “Pendulum” | 1842 | $38 | $1,093 |

| “The Tell-Tale Heart” | 1843 | $10 | $315 |

| “The Black Cat” | 1843 | $20 | $631 |

| “The Raven” | 1845 | $9 | $277 |

| “The Cask of Amontillado” | 1846 | $15 | $426 |

| “Ulalume” | 1847 | $20 | $562 |

| “Annabel Lee” | 1849 | $10 | $308 |

Sources: “Edgar A. Poe: His Income as a Literary Entrepreneur” and In2013dollars.com

3.

So, where exactly does the hope come in?

It’s true Poe’s unending financial problems did not make his life happier or longer and likely constrained some of his writerly impulses. Catering to the market was hardly his first choice, and he remained ambivalent about writing for an audience and magazines he sometimes saw as beneath him. “The poem which I enclose,” Poe wrote to his friend Willis in 1849, “has just been published in a paper for which sheer necessity compels me to write, now and then. It pays well as times go—but unquestionably it ought to pay ten prices; for whatever I send it feel I am consigning to the tomb of the Capulets.”

Then, of course, there were other people’s feelings. Poe’s attempt to adapt to the market did not go unpunished in his own day. “Hints to Authors,” a semi-veiled takedown, was first published anonymously in a Philadelphia paper in 1844: “Popular taste is sometimes monstrous in character…judging by the works and mind of its chief and almost only follower on this side of the Atlantic, it is a pure art, almost mechanical—requiring neither genius, taste, wit nor judgement—and accessible to every contemptible mountebank.”

And the commercial stink has never quite worn off. It seems to be among the reasons Henry James and Aldous Huxley—who likened Poe’s poetic meter to a bad perm—criticized him so harshly. Marilynne Robinson has noted how “virtually everything” Poe wrote was for money: “This is not exceptional among writers anywhere, though in the case of Poe it is often treated as if his having done so were disreputable.”

Yet commercial pressure arguably pushed Poe in the direction that saw him write some of the most lasting work in American history—even world history. I can only speculate, of course, but I think that if Poe had had his druthers, he’d have gone on with the pretentious poetry and abstruse dramas he initially favored. I seriously doubt we’d still be reading him now. Just try pushing through “Al Araraaf.” It’s like sitting down to a lengthy phone call with an elderly relative. You love this person, but it’s a chore.

We tend to view popular success with a skeptical eye, just as many did in Poe’s day. We tend to think of commercial pressure as corrupting. What if it can be also a positive, transformative force? Certainly, the ability to speak to millions of people across 17 decades is not a bad thing. It’s a real-life superpower. We should all be so lucky.

On that point, consider how conditions for freelancers and other writers have improved since Poe’s time. As Tyler Cowen relates in In Praise of Commercial Culture, today more people than ever receive basic education. Vastly more people receive higher education. The cost of art materials has fallen tremendously (think of the price of video equipment just 30 years ago compared to today). And you no longer have to go to a particular concert hall or museum to access art; you can just Google. By comparison, Poe’s couple of decades as working writer really sucked.

So yeah, hope. When I first cracked back into Poe last October, my therapist begged, “Please stop reading him. He’s too depressing.” But my experience of reading Poe and other writers on Poe the last 11 months has been the opposite of depressing. It helped me climb out of a very deep hole.

In the end, Poe only pocketed $191,087, but he did get the immortal fame he grew up dreaming of. And I got taken, blessedly, outside myself. If the past is anything to go by, what lies ahead is not destruction. It just might be the stuff of our wildest dreams.

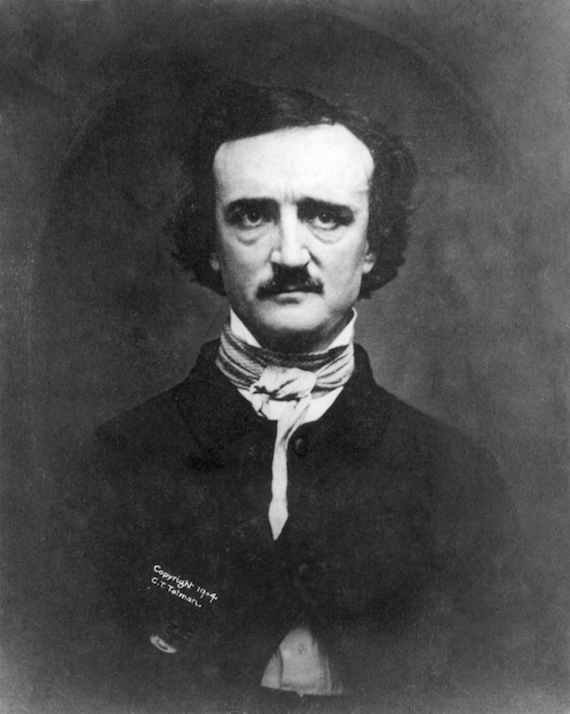

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.